Let’s imagine I want to write an essay with a farfetched thesis: your dreams can predict the future, accurately. Of course, it’s a stretch. But if I went for it, what would I need to convince a reader of this superstition? Science. Historical examples. Personal stories. I’d need to consider the skeptic and imagine their objections in advance. Whether my thesis is ordinary or outrageous, what I need is Material.

Material is the substance of your essay, the assemblage of found things that get woven into a linear reading experience.

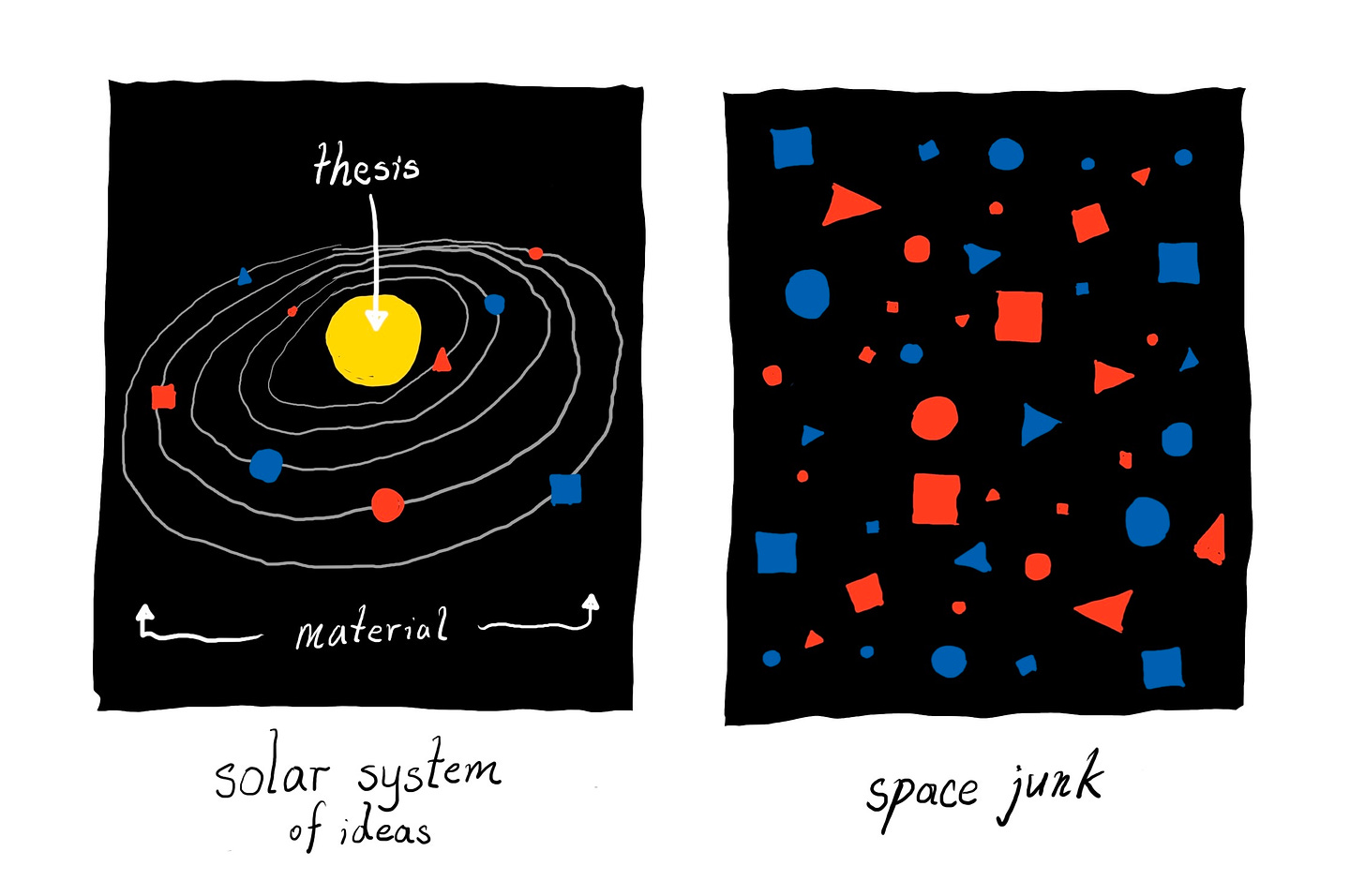

If a Thesis is the sun at the center of an essay, then Material is the swirl of ideas that orbit it. While a thesis is stubbornly singular, your Material is expansive. Wildly different things can coexist in the same space, but under one very important and non-negotiable rule: they should all relate to your thesis. Otherwise, you don’t have a system of ideas, you have paragraphs of space junk.

As a writer I collect rare materials, and so I always need to be careful not to hoard cheap shit from yard sales. I need solid collection constraints; “dreams” is far too broad. I don’t want to include everything from my dream journal, the science of lucid dreaming, or anything from the movie Inception. My thesis is on “precognitive” dreams, dreams that end up happening in your waking life. From this more specific lens, I can dive into Minority Report, the (bogus) predictions of Nostradamus, and the time my great grandmother saw the winning horse numbers for the next day’s race, three times in a row, and gambled and won (true or not, this a legend in my family).

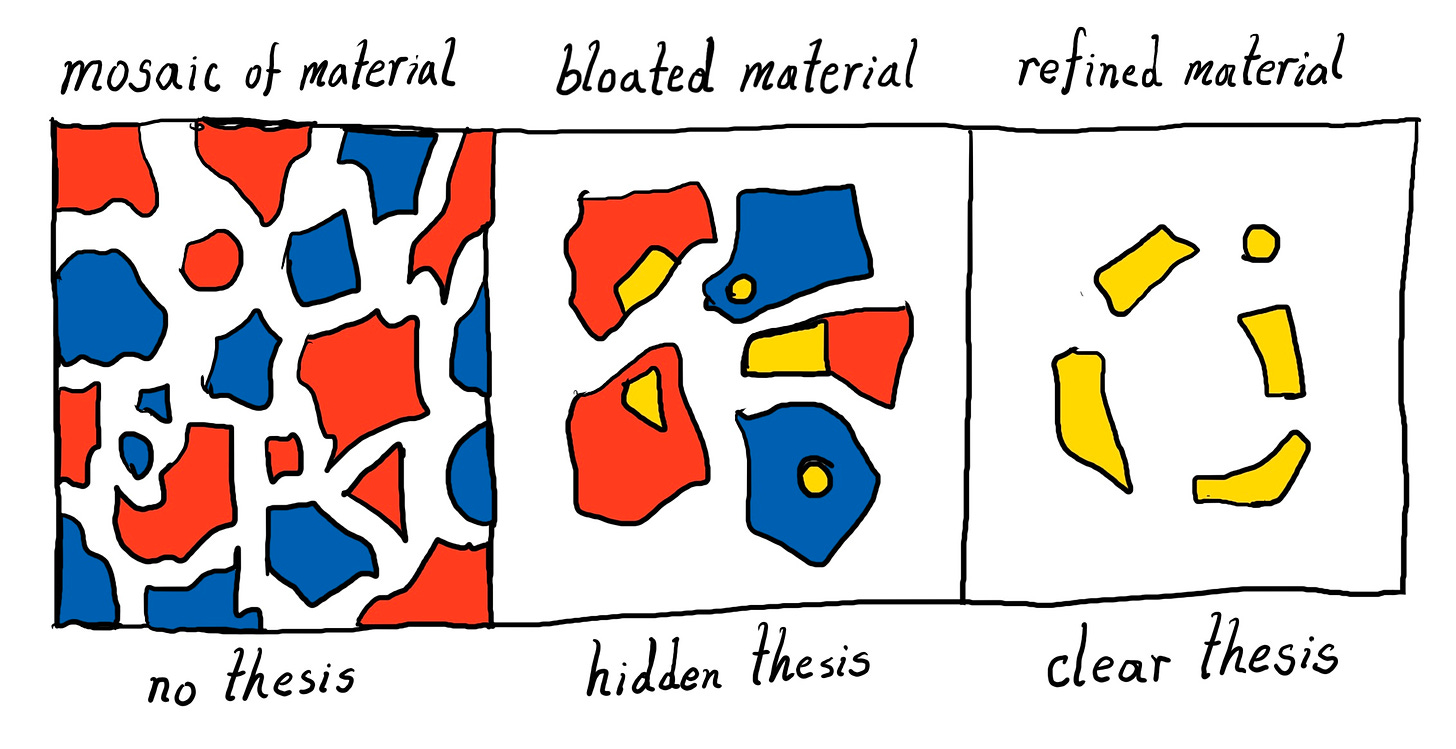

Your thesis is the filter that helps you collect absurdly specific facts and stories, but what if your thesis is fuzzy? “Precognitive dreams,” is an apex example of fuzzy thinking. It’s not even a thesis, it’s a topic:

Am I saying that the soul can time travel? Am I saying that our future is predetermined? Or, am I saying that a broken clock is right twice a day? Can coincidence drive the layperson insane? Maybe the brain is inconceivably good at pattern recognition? I don’t know my angle yet, and I won’t begin to know until I write a draft.

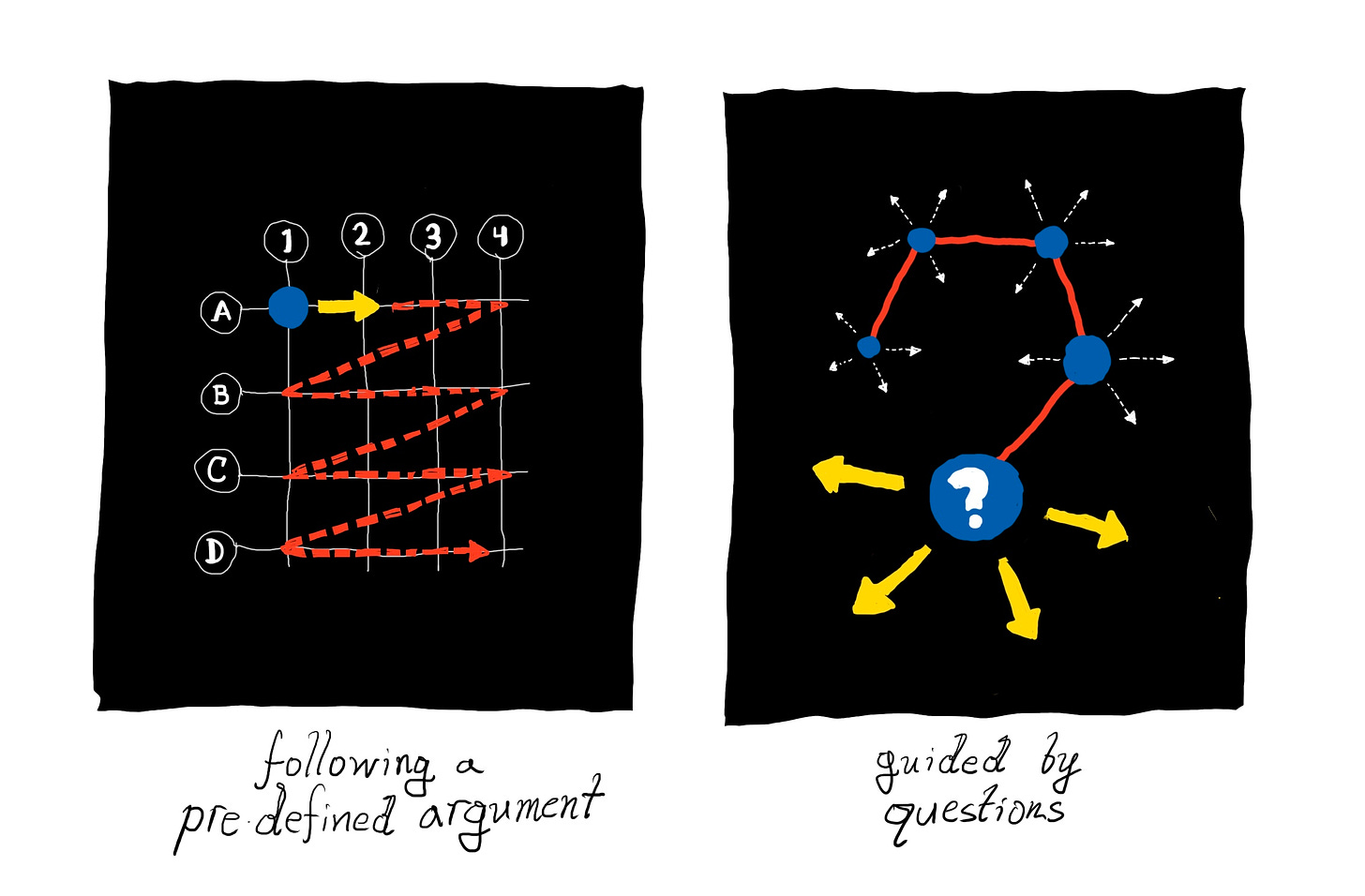

According to Paul Graham in “The Age of the Essay,” the idea that writers need to start from a fixed, unchanging center is an “intellectual hangover” from the Middle Ages, when most schools were law schools. Material isn’t just ammunition to defend a preconceived thesis. Material is a vehicle to advance your thinking. Through putting your experiences, thoughts, and research into paragraphs of your own, you see the holes in your ideas, and that opens questions, and those questions point towards new silos of Material to consider. As if by dream logic, you jump from one association to the next, gathering nodes that hopefully crystallized into a refined thesis.

The problem is you inevitably amass so many options that nothing makes sense anymore. Let’s imagine my early drafts lead me to read “Synchronicity” by Carl Jung, which is loaded with precognitive dream examples, and now I’m considering 3 new, competing options for a thesis. How does it all fit together? Where is the center? Material has the capacity both to enlighten and burden you. This is totally normal. In the exploration process, the writer spirals into complexity and knows not where to restart. Take it from John McPhee, who opens his essay “Structure” with him on his back on a picnic table, looking up at the sky, panicking over his mess of Material as his deadline looms:

“The subject was the Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey. I had spent about eight months driving down from Princeton day after day, or taking a sleeping bag and a small tent. I had done all the research I was going to do—had interviewed woodlanders, fire watchers, forest rangers, botanists, cranberry growers, blueberry pickers, keepers of a general store. I had read all the books I was going to read, and scientific papers, and a doctoral dissertation. I had assembled enough material to fill a silo, and now I had no idea what to do with it.”

— John McPhee in “Structure”

What you don’t want to do is keep everything you find. A mosaic of material drowns your reader in confusion. They don’t know how things are connected, or why the writer jumps from one scene to the next in a dream-like procession.

What you want to do is cut. Abandon most of the Material you find, and select just a few pieces that work together to show a pattern. Keep pruning, relentlessly, until a little collection of rare Materials convey a big idea with ease.

Today, we’ll get into:

How to sift through silos of Material to find a solid Thesis.

Why personal experience and cultural references are equally important.

What you need to build arguments (points and counterpoints).

Sifting through silos_

Rarely do I start an essay knowing the perfect 3 examples to weave into it. Rather, I need to immerse myself in an unreasonable amount of detail, and look for patterns in the noise. There are plenty of archetypes for the scrupulous searcher. An essayist is a kid who finds faces in clouds, an amateur altcoin trader who gazes into graphs, or a beach goer with a metal detector. Only by sifting through the sands of information can we find any shells worth stringing into a necklace.

We have vast reservoirs of things to tap into: memories, unread books in our libraries, dream journals, whatever. From these different places, we pluck things. We pluck them out of their original silos and put them all next to each other.

Could there be a shared thread between 1) my great grandmother’s trippy dreams, 2) Dune 2, and 3) J.B. Rhine’s parapsychology experiments at Duke in the 1930s? Each of these sources are composed of intricate sub-parts. On the surface, a collection of Material might seem random; but when you look carefully, you can find a pattern that connects them.

One of the main sins of scoping Material is a refusal to abandon the form you found it in. We often see stories through a fixed frame, often a beginning, middle, and end that have to flow in a specific order. It’s like when someone says, “Oh my god, I need to tell you about this dream,” and then chronologically runs through an absurd 10-step sequence, instead of just sharing the one detail that actually matters. So many times, a three-paragraph rant works better as a single sentence.

Through being incisional, we cut into our Material to see its indivisible and rearrangeable parts. We have to sacrifice the precious originals, melting them down to scraps, goo, and dust, so we can rebuild our own original work from the scraps. I wrote about this in The Alchemy of the Rewrite, but here’s a diagram that breaks pattern recognition down into a cartoon sequence.

SEGMENT: What are the subunits of this Material that stand on their own?

LABEL: How can I name each part so that I see this Material as a constellation of memorable concepts?

MATCH: If I focus on one subunit at a time, which other subunits are most related to it?

EVALUATE: What are the distinct themes running through my Material?

EXTRACT: Can I recombine a few parts to create a strong pattern, and cut the rest?

This is a semi-technical skill that is probably hard at first and becomes intuitive over time. What’s more important than any step-by-step process is the meta-skill. Writers need the patience to sift through noise on their search, and the agility to abandon old models in light of new information. Consider how Ken Burns assembled 10,000 hours of archival footage to review for his 18 hour documentary, Baseball. That’s a ratio of over 500:1. But creative waste isn’t a bug, it’s a feature.

Radical exposure, paired with a discerning eye, puts you in a position to weave together unlikely parts into a unique, integrated whole.

I’m not saying you should stop writing and go on a research binge. I’m asking you to spend as much time reading your draft as you do writing it. If you riff something out in 45 minutes, spend another 45 to analyze the Material on the page.

The fusion of memoir and research_

There’s a huge array of what can be considered Material, but I think it helps to classify everything into two opposing buckets. In the realm of personal Experience, we have anecdotes, stories, scenes, memories, dreams, journals, perceptions, family history, AIM logs, etc. In the realm of cultural References,” we have name drops, facts, summaries, commentaries, graphs, charts, quotes, excerpts, links, etc.

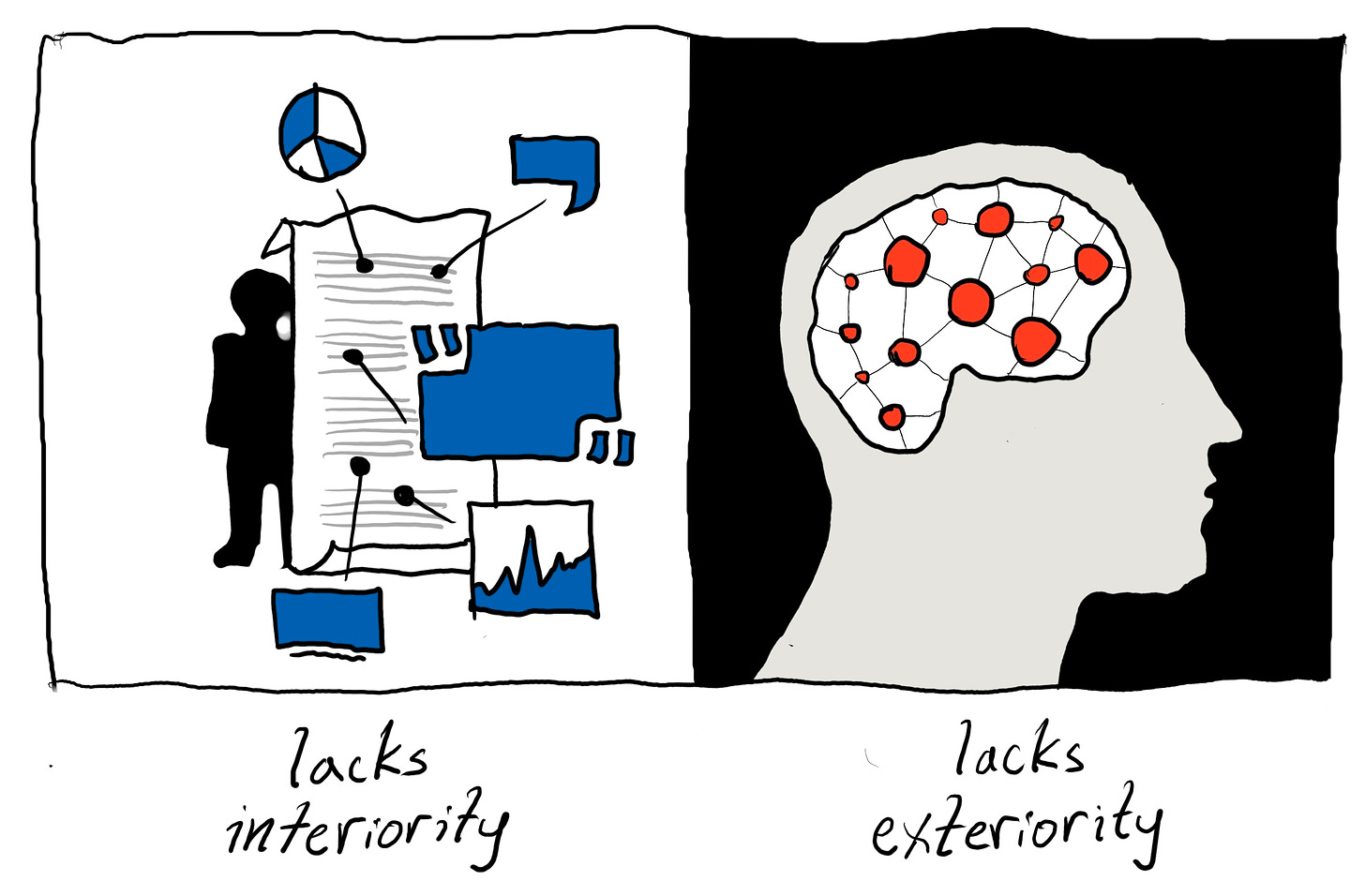

Obviously, feelings and facts can co-exist in the same essay, but there’s a 450-year debate on how one type of Material is holy and the other is forbidden. This has fractured the essay into competing mediums. “Articles” use factoids to make mechanical arguments, while “opinion pieces” weave feelings in an organic stream. In articles, the author has no presence. In personal essays, the author’s presence is all there is. One optimizes for objective truth, the other for subjective honesty, and both camps are scared of being wrong.

If the author isn’t on the page, the reader misses out on the human element. Why do they care about this topic? Inversely, if all we see is the author’s life, the reader can’t connect stories to the larger culture.

Of course, academic papers should lean towards research, and memoirs should lean towards experience, but the essay is such a powerful medium because it allows for the fusion of genres. When you integrate the two, you weave a web of supporting Material that is both relatable and credible.

Personal experience makes an essay idiosyncratic. The word “personal” is up for debate. When I say it, it means more than thoughts, feelings, or voice. To me, personal implies biographical details. It implies author-turned-character. What string of events led to a unique point of view? Perspective is downstream of experience.

If I were to ever write an essay about precognitive dreams, I’d have to include my weird family history around the matter:

My great great grandmother was rumored to be the psychic midwife of her town.

My great grandmother believed that God helped her gamble on horse races.

My grandmother interprets every dream symbol and coffee grind.

My mother is a fan of American pop-medium, John Edward.

My father, an MIT structural engineer, rolls his eyes at dream-talk.

There’s a unique backstory and tension here, and this isn’t even getting into my own experiences yet (which I’ll do soon). The point is, my life is a reservoir of Material that nobody else has access to. This is my moat. By tapping into this, I write the essay that only I can write. No one can put their name on that essay and get away with it. A large language model can read trillions of words, but it won’t ever learn the rumors of my ancestors.

Cultural references make an essay verifiable. While experiences are singular and sometimes dubious, references are nodes in the public domain that anyone can point to. Does the thing have a Wikipedia page? Here is a fact-salad about the topic at hand:

Precognitive dreams are a theme through the history of literature, from Homer, all through the Bible, to Shakespeare and Stephen King.

One night, the wife of a Roman ruler had a dream that her husband would be killed, and she warned him. The next day, Julius Caesar was assassinated in the Senate.

63% of Americans report having at least one precog dream in their life.

In 1927, J.W. Dunne (an ex-aeronautical engineer in the British military) proposed a theory that dreams enable people to experience time non-linearly.

Freud and Jung fought over this.

I’m not arguing that any of these facts prove or disprove a thesis. Including this kind of Material shows that I’m not trapped in my own bubble of experience. It shows I’m aware of how events from my own life have parallels in the public domain.

It’s never been easier to connect the dots. I learned about all 6 bullets above through ChatGPT; I’m sharing this to remind you that there are no serious barriers to grounding your experiences in culture. Before the Internet, academics had to fly to get their sources. Now I can upload a draft, and it gives me a list of references to read into.

If my essay only consisted of a fact salad, it would be generic and non-distinct. But the fusion of feeling and fact creates a special fabric, one where history colors experience and experience colors history.

I’m not saying all essays need memoir-resolution stories and MLA-cited research. Naturally, essays lean in one direction or the other. Experience-heavy essays can include a few powerful facts, and Reference-heavy essays can get personal by sharing a few relevant anecdotes.

An awareness of these two spheres is a good start, but it’s not enough. You eventually want to make sure your Material is actually convincing. You don’t want to build a maze of facts and feelings that do nothing to advance your thinking or clarify your thesis.

Consider the skeptic_

If I were to write an essay on precognitive dreams, I’d probably start with the snake story.

One day, ten years ago, in the suburbs of Long Island, I walked out of my parents garage to find a 5’-9” yellow snake in the driveway. This was not a dream. The snake and the outdoor family cat were circling each other, each hissing, as if they were about to rumble. I grabbed the cat, ran inside, and from the window I watched the beast slowly slither away. I’ve seen small garden snakes in the yard, but this? Was this an illegal pet that escaped? It was a situation out of a dream. What made the weird event even weirder is that the night before I dreamt it. I dreamt of a big yellow snake dueling a chipmunk in red boxing gloves (the chipmunk symbolizing my cat, of course).

Yes, this actually happened, and it boggles me. While I could jump to the definitive conclusion that I come from a lineage of psychics and now commune with the snake realm, it would be foolish to not consider the Law of Large Numbers. The average person has 100,000 dreams in their life, and so 1 of them is destined to be profoundly coincidental.

A bad argument is one that ignores the skeptics and builds a mountain of evidence for a single side of an issue. If I insisted, “my experience is true, and this happened all through history too, therefore prophecies are real,” that would be shallow logic. If all the Material points to a single and spectacular conclusion, something’s off. If you’re not willing to earnestly consider the opposite of your thesis, you’re bullshitting yourself. If you know counterpoints exist and you decide to omit them, you’re either lazy or lying.

A good argument would embody the view of the skeptic and take the counter-position seriously. It would go through each claim (sub-argument) of a thesis, and amass evidence for and against it (points and counterpoints). It doesn’t just stop there. By writing through the tension, you think critically, and come to more interesting conclusions and questions.

Imagine the flow of this essay: it would start with the Great Snake Mystery (a personal Experience). It would then mention that Cleopatra also had a precog snake dream, followed by a machine-gun spatter of quick, historical, prophecy References. So far all these points are evidence for my thesis. Then comes the Law of Large Numbers; it’s a counterpoint, a reference that deflates everything. Bummer, what next? I write to explore the tension, and there’s three general paths I could take, each of which unlocks new silos of Material:

I could challenge: I’d find new Material to disprove the skeptics. Technically, I did have another precog dream come true: just two years ago, I foregleamed a fight between my wife’s Doberman and a large raccoon. This could lead to a refined thesis: I can see the future, but only futures that involve domestic animal violence (likely, not an angle I’d take). Next…

I could compromise: Maybe there’s a middle ground. Maybe dreams don’t let us escape space-time, but perhaps our subconscious is just a good pattern engine. The brain registers a lot of material below our threshold of attention, and so at night it naturally plots out possible futures (ie: job promotions). We tend to remember the few that actually happen. But how do you account for an exotic 1-of-1 snake encounter? Maybe the snake was sleeping in the bushes from the night before, and pheromones came through an open window to trigger the dream. I looked it up, and while snakes can smell up to 300 feet, the human range is closer to 3 feet. It’s more likely that the snake was dreaming about me. Next…

I could concede: I could admit that I’m not a psychic, and make fun of myself for ever believing I was. This could prompt a whole riff on why humans have the impulse to retroactively assign meaning to vague signals. Is this impulse good or bad? That’s a different question, a hard question, a great question, a question that only comes up through going deeper on your Material.

An important point of this example is that you don’t always need to prove your thesis right. Sometimes, proving yourself wrong is more interesting. Through considering the skeptic, you unlock other silos of Material; it creates a richer experience for the reader, and it deepens the logic of your idea.

To put this simply, there are 4 types of material that an essay wants to assemble: personal Experiences, cultural References, things that prove you right, and things that prove you wrong. Without experience, it’s an article. Without references, it’s a journal. Without counterpoints, it’s propaganda. Through the intersection of these tensions, your essay becomes a proxy for a ruminating mind.

The next 3 posts for Essay Architecture will dive deeper into these patterns:

Experience (putting yourself on the page);

References (linking into the constellations of culture);

Logic (building sound arguments).

These upcoming pattern posts are for paid subscribers of Essay Architecture, but everyone will still get a free preview. If you’re an independent essayist looking to upgrade your craft, it only costs $100/year.

Let’s riff:

+1s: Which points around Material resonated with you and why? Do any other examples come to mind that you’d like to share?

Challenge: What do you disagree with and why? Let’s make this tighter.

Dreams: What’s your weirdest dream that seemed to predict the future?

Introduce: If you’re a new subscriber here, feel free to say hey in the comments and tell us about your writing goals and challenges (or, you can reply to this email).

Share: If you found this essay helpful, consider sharing it so more people can find my project.

Ok so a few questions: have you written the textbook or is it a work in progress? Have you considered selling your graphics on something like teachers pay teachers specifically with the tag that they are intended for students with Dyslexia? Have you been told that you have one of the better substacks on the topic of essays? In my opinion you do.

Keep producing awesome content! I’ll make sure to spread it around as much as I can.

Wait, are you NOT writing the snake essay?? You have to! I can’t wait.

This was SO enjoyable. I think it would be helpful to show examples of how you’d trim the fat and what exactly you might cut in a piece if it didn’t support the thesis. Especially if the thing you’re cutting seems really good, like if it’s entertaining, funny, shocking, etc. I suppose this is another way to say kill your darlings, but how do you know which darlings deserve to stay on the page and which don’t?