A Pattern Language

You don’t need templates, advice, rules, or Rick Rubin; you need to become fluent.

I

Writers get nauseous around rules because we’re bobbing in an ocean of disjointed advice.

We’ve turned off a whole generation to writing by forcing them write 5-paragraph essays on Of Mice and Men with MLA citations—myself included. In high school, my mom got a phone call from my English teacher saying I sucked beyond repair. In a college writing course during freshman year, I procrastinated on my first assignment until midnight before the deadline, when I proceeded to smoke weed and write an essay titled, “Honestly, here’s why I don’t want to submit this.” Unexpectedly, my teacher loved it. She granted me reign over my semester to write and say whatever I wanted and I got an A.

Ms. Houch unlocked something. The freedom from rigid rules turned writing into a process that was fun, anarchic, expressive, liberating, meaningful—the kind of challenge I could spend my whole life on. Over the next decade—as I pursued architecture—I wrote essay drafts as a hobby. I didn’t have Mrs. Jackson’s proverbial gun to my head; it was a way to make sense of things in my life (Will virtual reality ever catch on? Is Frank Lloyd Wright an asshole? What do I want from my life? Why am I afraid to try psychedelics?). Only once I found the independent drive to write essays did I discover the limits of my craft, the challenges of editing, and the flimsiness of my beliefs. Only once I started reading classic essays that survived the melt of time did I realize the large and taunting delta between what I am and what I could be. If I wanted to get good I would have to… learn the rules I once rebelled against.

While our canon of books on writing is rich, timeless, and inspirational—spanning thousands of years from Aristotle to Stephen King—it’s also a fragmented mess.

The most popular books on writing are more motivational than technical; they figure if you just keep showing up, eventually, you’ll figure it out yourself. There is some truth to this, but a blind routine has diminishing returns and you’ll eventually write yourself onto a quality plateau. You can only go so far in Rick Rubin Mode; I’m not against intuition or authenticity—each matter, and Ruben’s nuances around the psychology of art are strong enough to unblock the best in any field—, I just think the bigger problem is the lack of a system to teach the basics.

The technical advice we have is either dense, impractical, or cheap; much of it is presented as (a) an unstructured list of pithy phrases (“Show, don’t tell!”), (b) rhetorical dictionaries of impossible-to-remember Latin phrases (“epizeuxis”), or (c) $29 templates that promise to Make Writing Easy. Of course, sound writing principles do exist, but they’re isolated, scattered, and disconnected from a cohesive system. You’re left with two options: an $80,000 MFA or figuring it out yourself.

II

For writing concepts to be effective, they need to be organized into a hierarchical and interlocking system: an architecture.

When you hear the word architecture, you probably think of a building—the Parthenon, the Empire State Building, the Guggenehim—but the word has a much broader meaning. Your mind has an architecture. Our government has an architecture. In the world of technology, there are software architectures, network architectures, information architectures.

An architecture is a hierarchical system of parts that come together to solve timeless design problems. There is a perennial need to build software, stories, and shelter. There might be billions of different buildings, but across each one is a lattice of similar decisions that went into its creation.

The book that best captures this idea is A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander. A “pattern” is a small recurring problem that you find across every design. It’s a “language” because (1) these patterns all link together, and (2) you can actually find the same set of patterns across every design. A pattern language is quite complex when you break it down analytically, but someone with fluency can shape original and beautiful designs, almost without effort. If you were to ask Alexander what architecture is, he might point you to his title: architecture is a pattern language.

A Pattern Language features 253 distinct design patterns, which are ordered from big to small and organized into a hierarchy: at the top level, he has 3 dimensions (the town, the building, the detail), and within each there are ~9 groups of ~9 patterns. This means that every architectural pattern is mapped. Designing a greenhouse? Flip to Pattern 175. Alexander writes about the goals, constraints, and opportunities of a greenhouse, and then hyperlinks you to all the related patterns: WORK COMMUNITY (41), VEGETABLE GARDEN (177), COMPOST (178), WAIST-HIGH SHELVES (201), etc.

This is fundamentally what writers are missing: a comprehensive language for composition. By calling this a “language,” instead of a “list of rules,” hopefully you see how it is expansive, not restrictive. Alexander says:

“Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.”

In any language, little units combine to make infinite possibilities. From just 12 musical notes, Debussy wrote “Clair de Lune.” From just 26 letters, we have the volumes of Shakespeare.

There are 1,000s of writing concepts you could study, but you don’t become fluent in a language by reading the dictionary. My goal with Essay Architecture is to distill the ocean of advice down to an essential “composition alphabet.” The 27 patterns in this system aren’t rules, tricks, templates, or solutions; they are the fundamental problems you’ll never escape. Through practice, you can learn how to weave patterns together to shape timeless essays.

III

The scope and flexibility of the essay makes it the best form of writing to master a pattern language.

It would have been nice to say, “Here is the ultimate system for all writing,” but that would be dishonest, considering that different forms have different constraints. Prose and poetry have completely different kinds of syntax. Fiction is focused on characters and world-building. Memoirs and novels are long. The essay, despite its troubled history and poisoned brand, is the perfect medium to learn and master a pattern language.

Someone could write a PhD dissertation on defining an essay, but for now let’s stick with a simple (working) definition:

An essay is a work of creative nonfiction fit for a single sitting, where an individual with a distinct voice expresses a unifying idea in a linear form.

An important feature of an essay is its relative brevity. Most new writers dream of writing books, novels, and memoirs, but crafting a 300-page beast on your first take is akin to going to the gym on day 1 and attempting to bench-press 300 pounds. An essay, on the other hand, can be written in a day—maybe in an hour. You can write many essays in a single year—from start to finish—and watch yourself become more fluent.

Also, by learning how to write essays, you get exposure to all of literature’s devices within a single format. Creative nonfiction is flexible; it amalgamates the best parts of other formats. The essay fuses the soul of the memoirist, the rigor of an academic, and the pen of a poet. While other formats have more specialized languages, the language of the essay touches all sides of literature, and every corner of the human psyche.

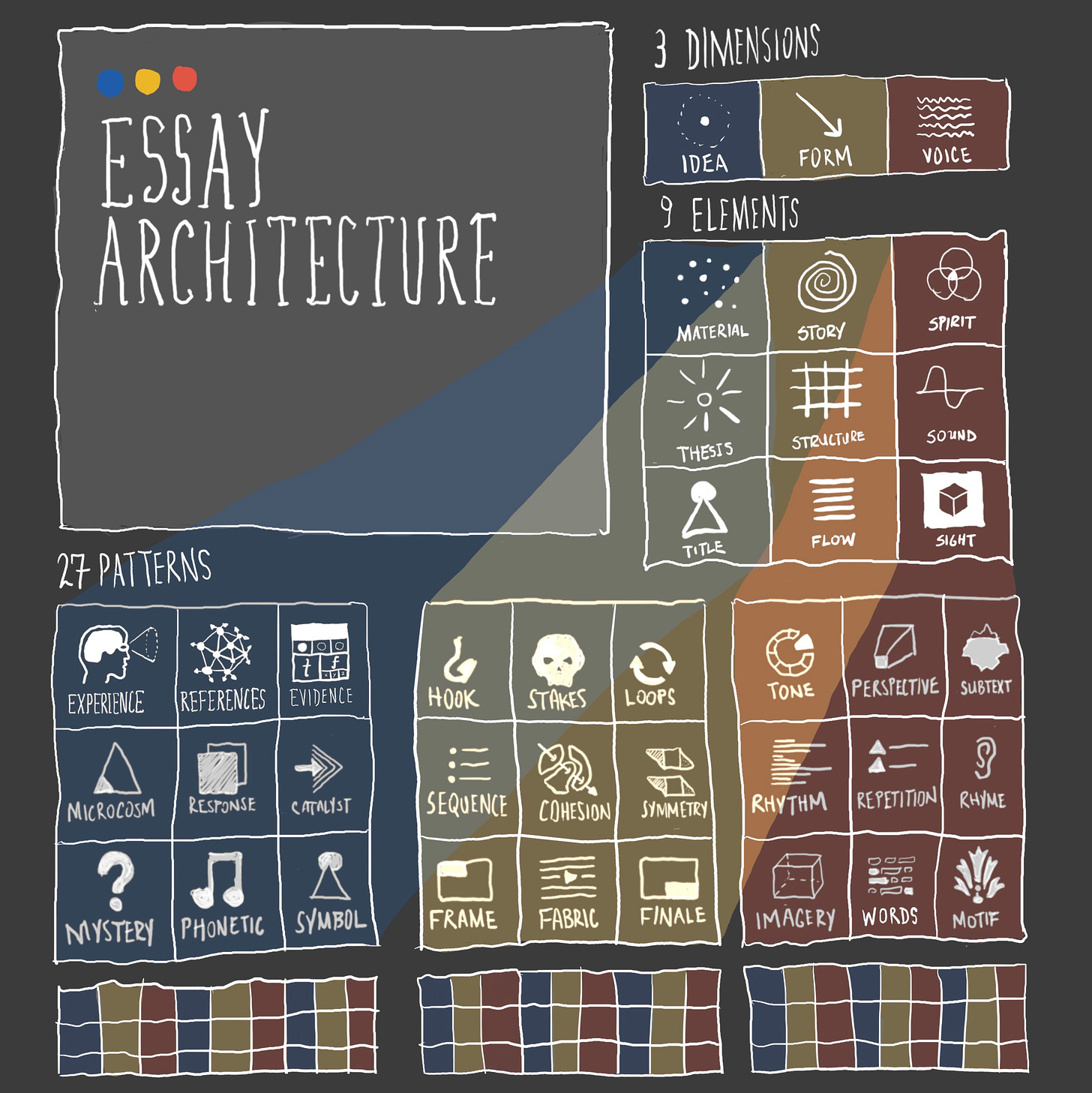

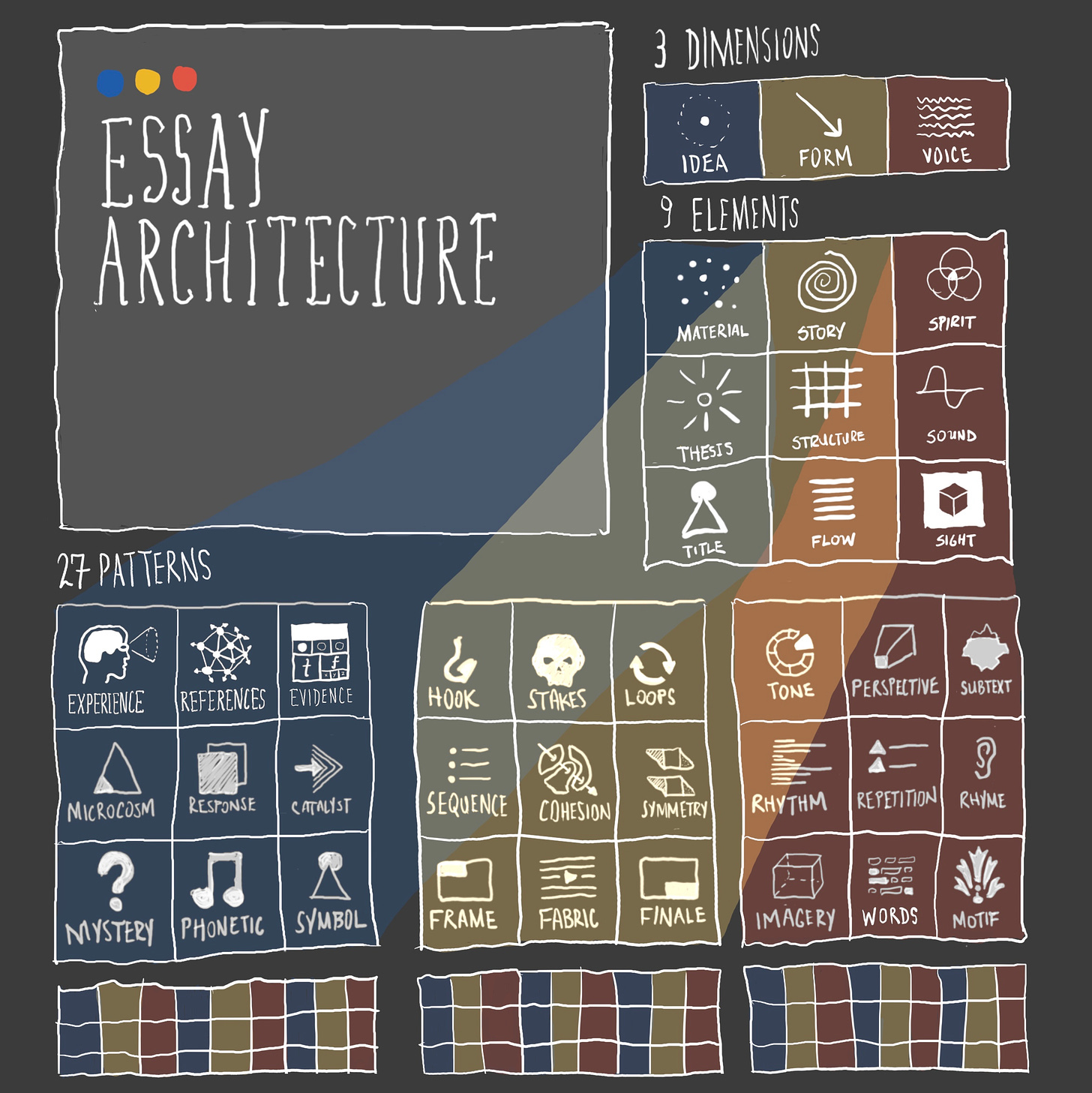

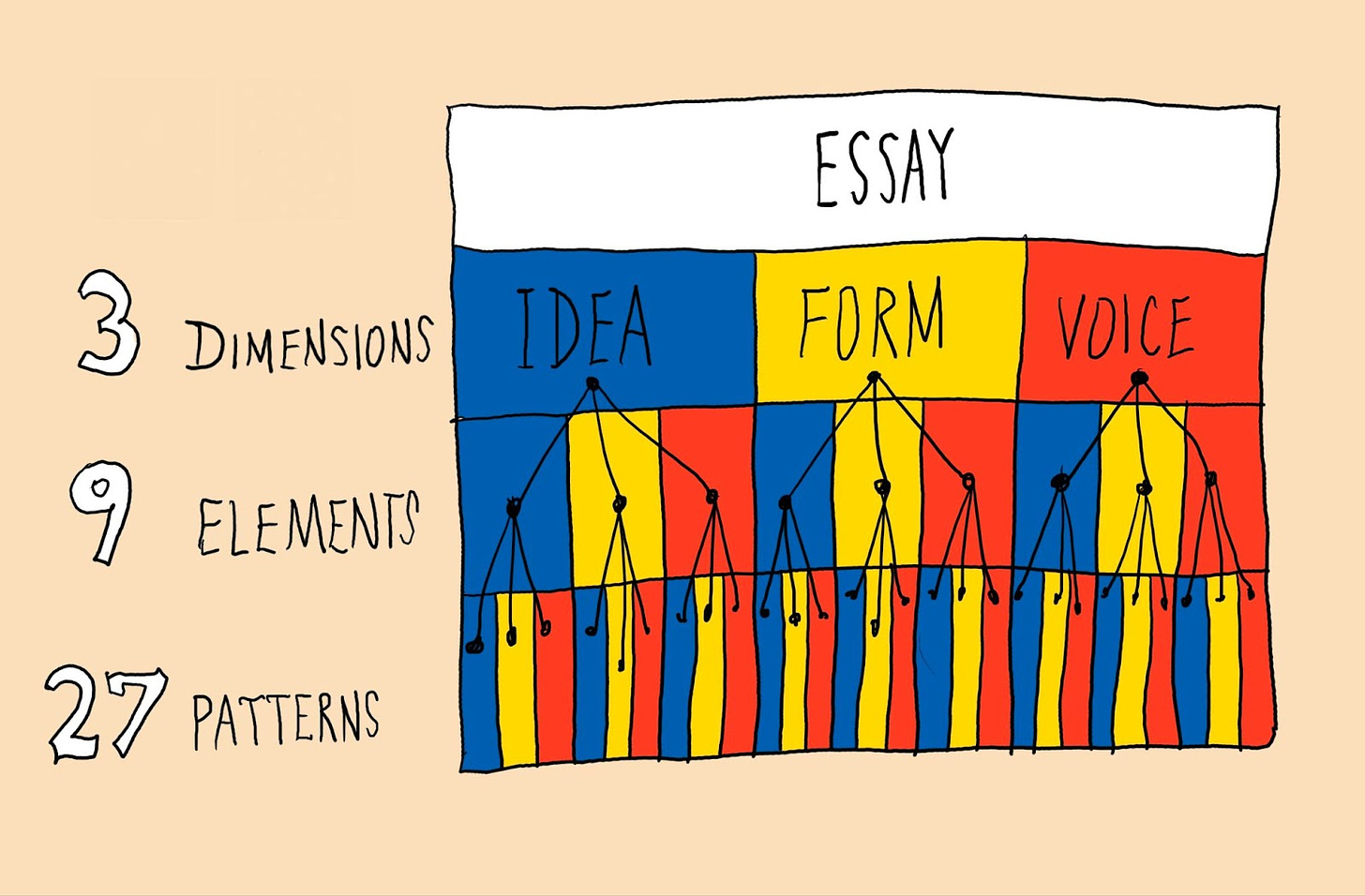

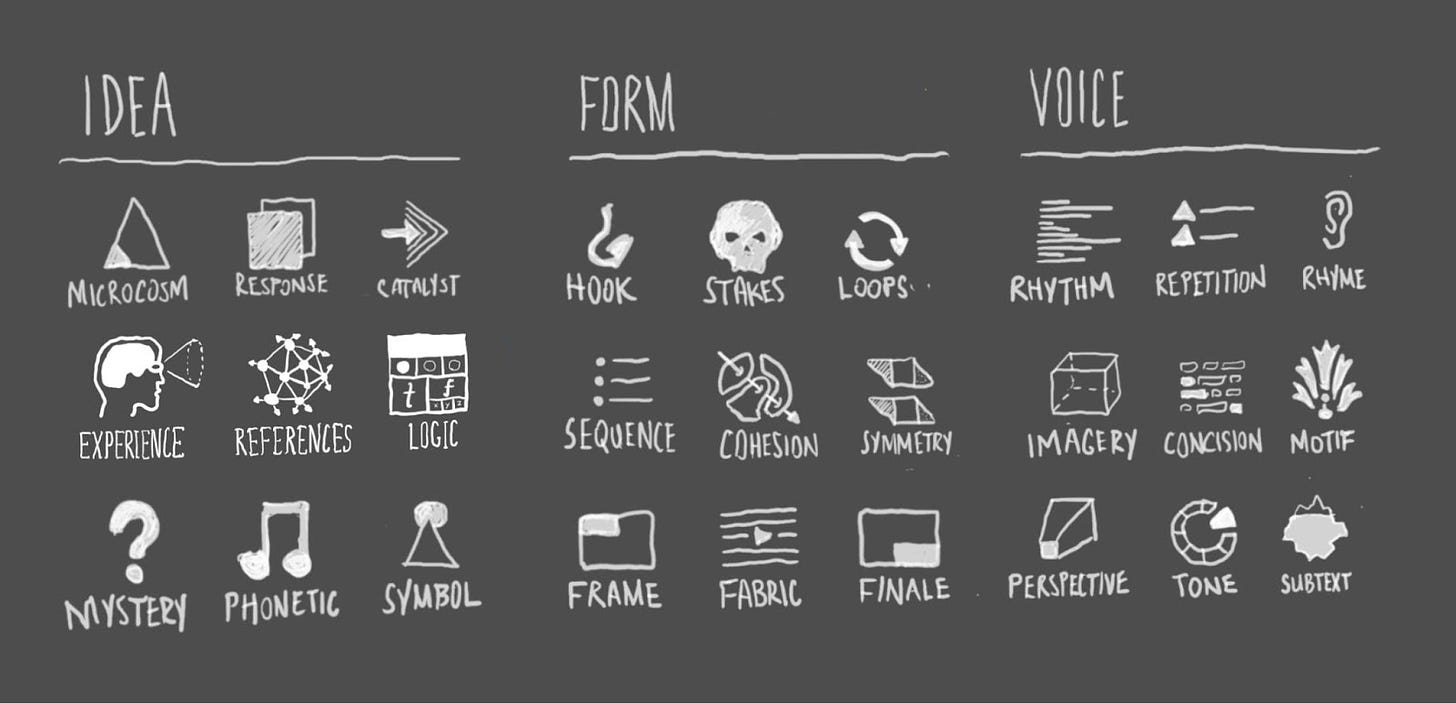

Inspired by Christopher Alexander, I’ve designed a pattern language for essays: it has 27 patterns, grouped into 9 elements, which span 3 dimensions

As you can see from this insane and probably intimidating diagram, I’m not proposing a quick tip. This is a comprehensive system; it’s complex but powerful, and my goal is to make it approachable. Considering it takes months or years to learn a language, why would you invest in this one? Alexander says:

“Many of the patterns here are […] so deeply rooted in the nature of things, that it seems likely that they will be a part of human nature, and human action, as much in five hundred years, as they are today.”

Essay Architecture is not something I invented, it’s something I found. You’ll find it too if you read closely. After dissecting hundreds of classic essays, editing a thousand drafts, and writing almost a million words, these are the invisible patterns I see in the page.

IV

Writing a great essay requires coordinating three distinct modes of thought; these modes have such a unique set of problems that each can be considered its own “Dimension.”

Alexander’s system is divided into three radically different scales: (1) the town, (2) the building, and (3) the detail. Consider how different the mindset and skill set is for each. At the scale of towns, urban designers are plotting roads and districts across topographies; at the scale of buildings, engineers are wrestling with gravity and calculating structural loads; at the scale of details, decorators are selecting furniture, plants, and finishes.

Each is an independent plane of thought, a unique problem-space, its own dimension. Their concerns are singular, yet their decisions are all intertwined.

When you get tunnel vision and obsess over a single dimension, you’re bound to either (a) create problems outside of your scope, or (b) waste a lot of time. Consider a facade designer who perfectly details every brick of a building before learning the team botched their zoning research; the whole shape is wrong and everyone has to start over. Architects, however, are known to be “master generalists”; they know the basics of each dimension and can orchestrate the whole design process for a building.

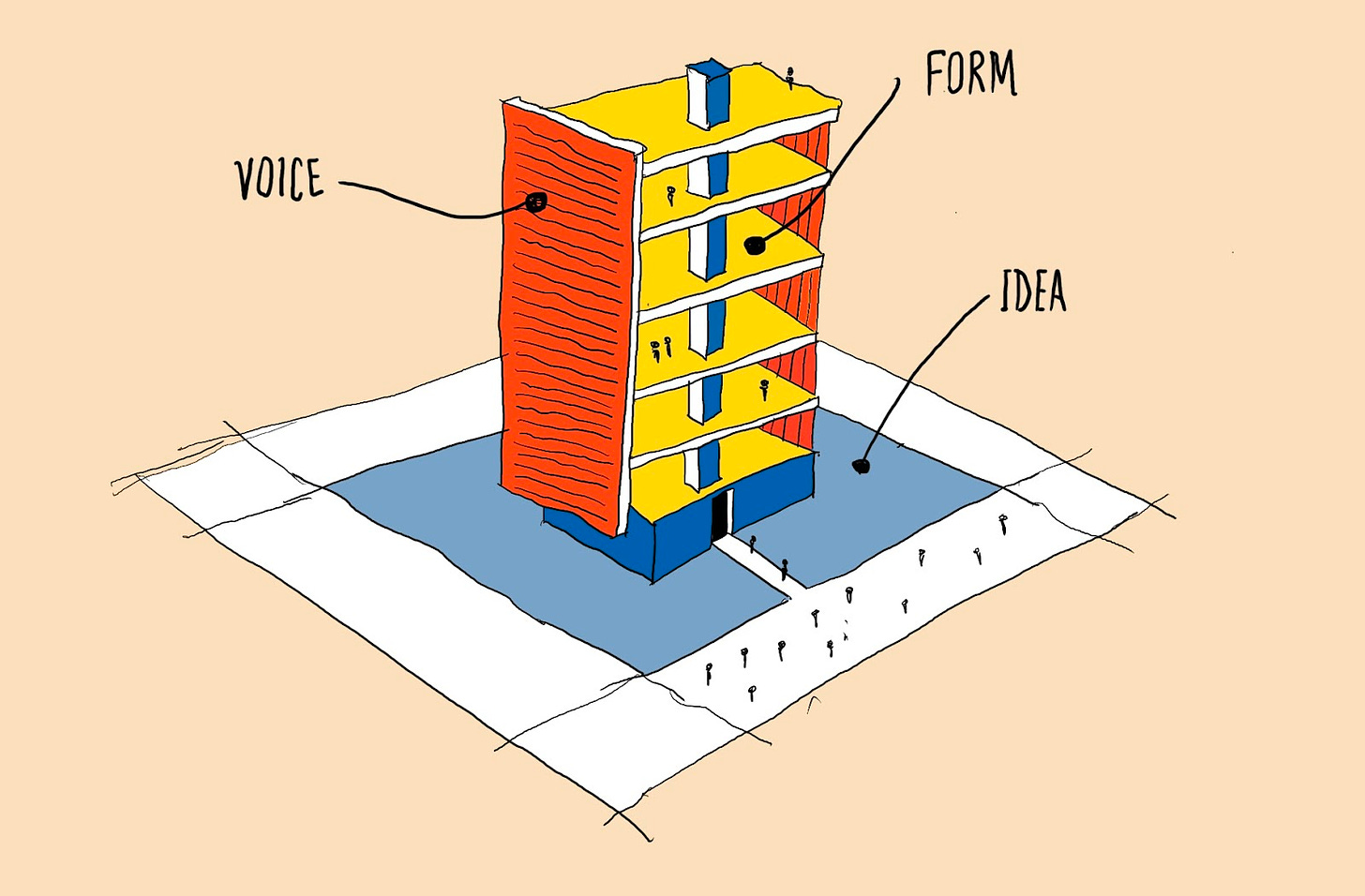

Similar to Alexander’s dimensions of varying types, an essay has three Dimensions: Idea, Form, and Voice. The essayist wants to think like a generalist so they can coordinate decisions across the different planes of thought.

When the writer scopes their Idea, they’re deciding where to place their thought-structure: out of all possible ideas, where is the origin of a given essay? That decision then shapes the Form, which is the thought-structure itself. An essay’s form is like the design of a floor plan; the reader circulates through a sequential arrangement of ideas. Of course, every surface needs to be tastefully detailed, so that’s where Voice comes in.

Notice how each Dimension zooms in? It goes from the big idea, down to the paragraph flow, down to individual words. It’s tempting to think the design process flows in a simple order (from big to small), but as we make a decision in one dimension, we need to consider its implications for the other two. The essayist has to become a nimble dimension-shifter, an architect.

These 3 dimensions aren’t new, they go back to Quintillian, Cicero, and Aristotle. The ancient ideas of invention, arrangement, and expression map neatly onto Idea, Form, and Voice. We’ve known these Dimensions for 2,000 years. The problem is that each Dimension is internally unstructured, containing an isolated flurry of rhetorical devices. Consider Elements of Eloquence; it’s a modern classic, but (1) it only focuses on one dimension, Voice, and (2) it lists 39 elements without a hierarchy. What’s actually essential to learn? Is polyptoton—the focus of chapter 2—really the second-most-important rhetorical device, or is it just one of several dozen forms of repetition?

If each Dimension contains a whole universe of concepts, then we need internal hierarchies to map each of these problem-spaces.

V

Every dimension is defined by three “Elements,” each of which has a unique geometry, a unique rhetorical appeal, and its own set of “Patterns.”

As an architect turned writer, I have a visual style of giving feedback; I don’t just red-line and copy-edit, I draw over essays with colors, lines, and shapes so that writers can see the invisible patterns in the page. Over time, over a thousand essays, it became clear that (1) the same elements were at play across very different essays, and (2) each element had a unique geometry.

At the heart of architecture is the idea that buildings are made up of primitive shapes. Francis Ching, known for Form, Space, and Order, teaches architecture through visuals. While most people break architecture down into different styles—Modern, Classical, Neoclassical, Gothic, Victorian—Ching breaks it down into elemental geometry: points, lines, shapes, volumes, and textures. Regardless of the style, you find the same geometries, even millennia apart. Architecture is a language of geometry, and so is essay-writing.

Within each dimension, there are three Elements; each has a unique shape, and they come together to form the totality of that dimension. The elements of Idea come together to make a center, the elements of Form come together to make a line, and the elements of Voice come together to make a texture.

In the left column of the chart above, notice how each element is categorized as “ethos,” “logos,” or “pathos”? These concepts are part of Aristotle’s system of rhetoric. This is another ancient idea; it’s about using the tools of composition (in speaking or writing) to communicate clearly, make good arguments, and convince your audience. He found that there are three very different modes of persuasion that could all work together, and if a work was missing one of them, it would be incomplete.

Ethos is about the character of the writer. In these elements, the author builds credibility by sharing their unique history, preferences, and spirit. There is personal authority in the writer’s idiosyncrasies. Without ethos, the reader won’t trust the person behind the idea.

Logos is about reason. Clarity emerges when the writer employs methods around logic, hierarchy, causality, etc. By refining an essay through analytical rigor, the writer builds credibility as someone who seeks order in their ideas and language. Without logos, the reader is mired in confusion and it distracts from the experience.

Pathos is about emotion. Reading is a sensory and psychological experience, and so the writer appeals to their reader’s emotions by immersing them in an aesthetic landscape. By crafting words with personality, beauty, and verve, the topic becomes relatable. Without pathos, the human touch is missing.

To put it simply, ethos is about the writer, pathos is about the reader, and logos is the shared fabric between them. This speaks to the tradition of literature as communication, as a bridge between writers and readers across space and time. It makes sense that you see this rhetorical triad at every scale of this system, not just at the Elements, but also up to the Dimensions and down to the Patterns. This pattern language is a fractal system, but it becomes approachable if you remember this simple, ancient triad. It’s Aristotle all the way down.

Now, here’s a brief overview of the 9 Elements.

An Idea is the substance of the essay; a writer curates a range of Material (1)—in the form of personal stories, cultural references, and evidence—to explore a topic. A Thesis (2) is the unifying concept; it makes the disparate ideas cohesive, while providing tangibility, context, and relevance. A Title (3) is the ultimate compression of a thesis; it serves as both an invitation into a thought-structure, as well as a souvenir out of it, so that readers can remember and reference it. Your readers have limited cognitive bandwidth, and so these three elements work together to create an unmistakable center in a large field of ideas.

All essays have a beginning and end, and so Form is the bold, linear path you carve through a topic. Given that you always want to propel your reader forward, Story (4) includes a range of devices to build tension and hypnotically draw your reader in. While Story is the feminine force of mystery, Structure (5) is the masculine force of order; through logically shaping the order of events and the clarity of themes, you can ensure your reader is never confused. While both Story and Structure cover the macro-arc—how you arrange 50 paragraphs—you always want to zoom in to the micro-arc, the Flow (6) between paragraphs. Paragraphs are your atomic unit of composition. Each one is a small loop where you orient the reader, build your case, and then close with a subtextual explosion that incentivizes them to keep reading. Readers are most likely to abandon ship when the Form is off, so it’s important to build intrigue, minimize confusion, and evoke a trance.

I believe every writer has the potential to develop their own voice, but that doesn’t mean we can’t deconstruct the Elements of Voice. At its core, the most identifying part of a writer’s voice is an intangible Spirit (07). There are hundreds of little decisions to make in the crafting of a paragraph; behind the words is an authorial attitude in the subtext. You might call this “tone.” This essence influences every decision, and it’s a texture that can be read across paragraphs, across topics. Sound (08) is about rhythm, repetition, and rhyme; these are each syntax patterns that can be used to enhance meaning by putting a spotlight on ideas. And writing, of course, wants to activate our primary sense of Sight (09). Good prose is laced with compelling imagery, along with rich words that activate specific feelings. Spirit, Sound, and Sight, when brought together, activate the reader’s nervous system. Reading strings of prose is cognitive labor, but good voice turns abstract language into a hallucination.

Essay Architecture is organized into 9 chapters (one for each Element) and within each you’ll learn about the 3 nested Patterns in detail. These 27 Patterns are the smallest recurring design problems that occur across every essay. No matter the type, length, or topic, you always need to think about sculpting ideas, arranging them, and rendering them with voice. Remember, these patterns are not restrictive solutions, but open-ended questions. I’m not saying, “you have to always use the Hero’s Journey”; that is just one of (at least) a hundred ways to solve the pattern of Sequence (5.1) within the Element of Structure (5). You can and should invent your own solutions, but you can’t ignore these fundamental questions.

In each Pattern, I’m going to propose 15 of the most common solutions. When you consider the permutations, there are 56 nonillion unique types of essays (56,815,128,661,595,284,938,812,255,859,375). Of course, there are more.

My thesis with Essay Architecture is that essays can and should strive to score a 5/5 in all 27 of these Patterns. While there are some classic essays that are mono-dimensionally great, there is precedent for essays that are nearly perfect across every Pattern. Over centuries, the essay has forked into dozens of specialized sub-genres: the personal essay, the historical essay, the lyrical essay, the travel essay, the philosophy essay, the article, etc. While we should celebrate variations in the medium—where certain Patterns are isolated and maximized—we shouldn’t forget that the Essay (without an adjective), is a medium of unity.

By writing essays that are informed by all 27 patterns, you’ll harbor extreme rhetorical power. That comes with real responsibility. Once you master composition, you basically wield the power of a literary psychedelic experience; you immerse your readers in a phantasmagoria, pull them along a guided intellectual meditation that they can’t look away from, and by the end you incept a single idea that can change the way they see, think, act, believe, and hope. This is the end-goal of literature; you write to transform your own consciousness, and then edit it into an artifact that might change the mind of a stranger in the future.

VI

It takes time to learn a pattern language.

Learning a language is slow and hard. Much of modern advice is incentivized to present itself as simple, but knowing a writing meme isn’t enough, even if it’s true. You can’t speak a language just by writing the alphabet; you need to weave the letters together to internalize it. In order to learn this composition language, it helps to focus on one Pattern at a time (starting with your weakness).

By learning about a Pattern, you shift from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence. You’re aware it exists, but you don’t know how to use it and it feels awkward. That’s okay. To start, it’s best to consciously think through Patterns in the editing phase. You have to be slow, conscious, and hyper-aware of it. With repetition, you’ll eventually shift from conscious competence to unconscious competence. The goal is to get to a place where you can forget about this whole system and have it come through automatically. Through analytical practice, you’ll be able to produce stream-of-consciousness gold.

Fluency takes time. We live in a culture of speed, and we sometimes forget the meticulous effort and sluggish pace required to internalize a new skill.

I want to take this one step further than Alexander; by making each Pattern quantifiable, I think writers could learn faster. With each Pattern, I’ll include a rubric that explains how to score it from 1–5. This lets you assess your own strengths and weaknesses around composition. In this case, scoring is not about an overall grade; it’s about giving you granular numeric feedback so you know where to practice. It still won’t be “easy,” but I think if writer’s can measure, accelerate, and feel their own arc of improvement, they’d be more motivated to stick with it.

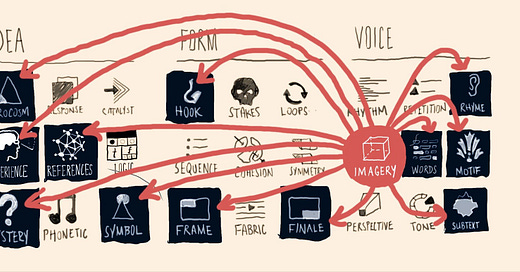

The reason you want to know and start with your weakness is because all these patterns are interconnected. The whole system is a hyperlinked web. By “fixing the hole,” in one spot, you’ll see a difference across all the other Patterns. For example, if you practice and get really good at Imagery (8.1), it will boost the Patterns that are linked to it. Your Material will become more lucid, your Titles will become eidetic, the hook of your Story will lure us into your world, etc.

“No pattern is an isolated entity. Each pattern can exist in the world, only to the extent that it is supported by other patterns: the larger patterns in which it is embedded, the patterns of the same size that surround it, and the smaller patterns which are embedded in it.” —Christopher Alexander

This means that there’s no specific order to learn Essay Architecture in. You can enter wherever you want and carve your own path.

This interconnectedness of parts shows that this whole thing is a language. Essay Architecture is the ABCs of essay composition, and just like how studying letters suddenly lets you shape words to form novel sentences, studying the fundamental units of composition will let you string beautiful ideas together so you can turn thoughts into timeless essays of extreme potency.

Thanks to for helping shape this essay at every level. In terms of Idea, he helped me see that ethos, logos, and pathos were already woven into the language. In terms of Form, he helped me find the right resolution to explain the system. In terms of Voice, he’d send screenshots of Garner’s Usage Dictionary as we debated commas and words.

Let’s riff:

Any experiences you want to share on learning a craft?

Were any parts of this essay an unlock for you?

What do you still disagree with?

What’s an open question in your mind?

Wow I love this, I'm definitely going to be rereading this again and again!

Thank you for an in-depth explanation and exploration of this. I'll be checking out "A Pattern Langauge!"

Michael, this is such a logical, inspired, and valuable extension of your thinking and experience in music and architecture. It is a gift to writers. Thank you for sharing it with the world.

Plus, wow. Just wow. 🙏 ⭐️🤯