Welcome to the first review of Dean’s List! Twice a month, I’ll break down classic works to show you the secret architecture behind essays. I’ve included links to the source, but don’t feel obligated to read them in full to appreciate this post. You’ll get context and a summary before I get into scores and craft analysis.

Links:

I went into “Against Interpretation” thinking Susan Sontag would hate my project. Essay Architecture is about quantifying and deconstructing the essay, and so I imagine she would have considered me a hyper-interpreter (which the title clearly says she’s against). It turns out, you can’t trust Sontag’s titles (“Notes on Camp” is not about summer camp). To my surprise, the end of her essay calls for a “vocabulary of forms,” which is uncannily, exactly what I’m doing. Maybe we would’ve gotten along.

Sontag became known in October of 1964 from her essay, “Notes on Camp,” (in case you don’t know, “camp” is a type of irony). A month later, she released Against Interpretation. This went on to be the title and feature of her first book of essays in ‘66, and it set her up to shape the field of criticism.

Her essay rails against interpreting the intentions of the artists.

The ultimate sin is for a critic to skew a work of art: “Look, don’t you see that X really means A.” It’s an act of translation. The worst kind of interpretation is one that ignores the literal dimension of the work (form), and instead treats it as a mere vessel to convey a statement (content). She shows us this impulse through history, and how different movements warped art to fit their own agenda.

“Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art.”

Interpretation impoverishes the world by setting up “a shadow world of meanings.” It makes some artists self-conscious, it makes other artists flee towards irony and abstraction that’s harder to criticize, and it dulls the sensibilities of society.

Sontag’s proposal isn’t to escape all interpretation, but to change it. She calls for a shift from “hermeneutics” (analyzing meaning) to “erotics” (analyzing the sensory effects that emerge from form). Don’t tell us what it means, but tell us what it is.

“What kind of criticism, of commentary on the arts, is desirable today? … What is needed, first, is more attention to form in art. If excessive stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more thorough descriptions of form would silence. … What is needed is a vocabulary—a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary—for forms.”

It feels like Essay Architecture is a direct response to this call to action. I’m building a non-prescriptive vocabulary of form for essays. I’m not analyzing writing to fit a political, historical, or moral agenda. I have no intention (nor ability) to psychoanalyze Sontag’s subconscious desires. This isn’t Pitchfork, either.

I simply pay attention to how an essay makes me feel, I notice how that relates to what’s objectively on the page, and then compare that to the patterns I’ve noticed across all the other essays I’ve read.

Given the alignment, what better essay than Against Interpretation to kick off this Review series? (I’m launching my critique series by critiquing a critique of critique).

So how does this work?

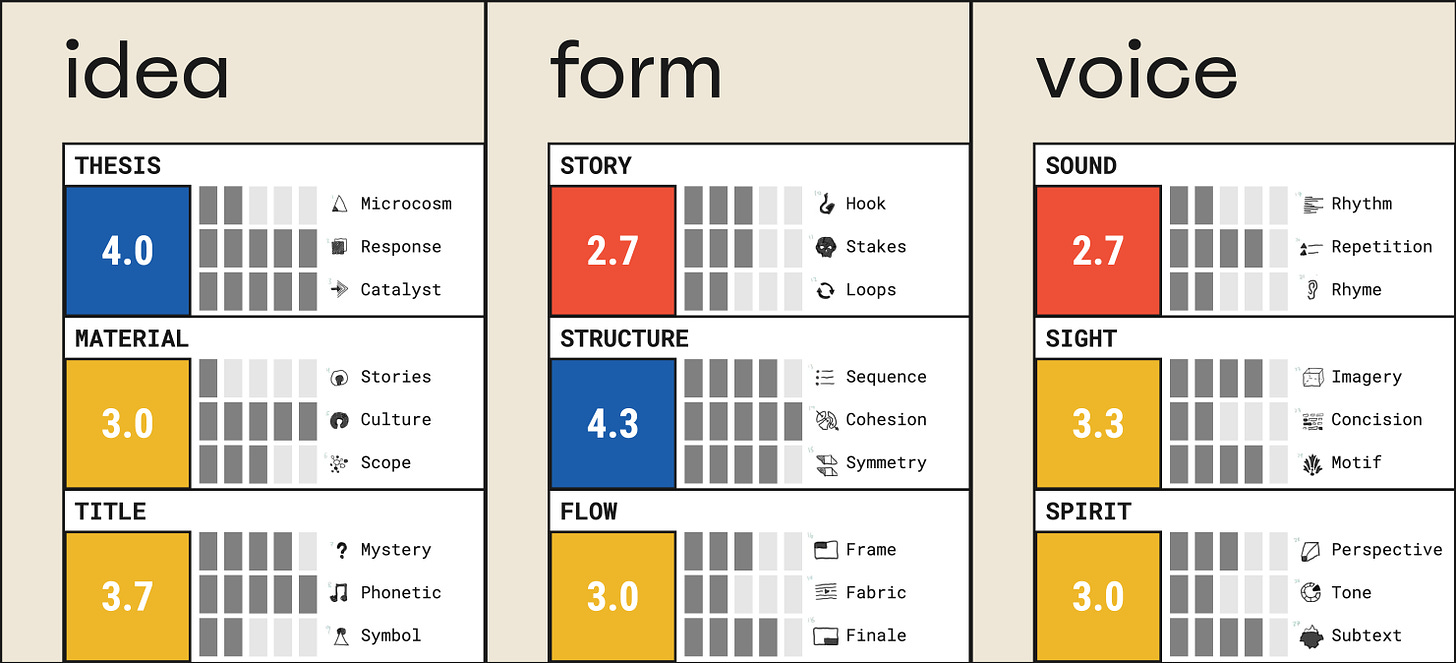

For every essay I read, I score it across 27 patterns—1 through 5—which you can see in the gray rectangles above.

Notice how patterns are in groups of 3? They come together to shape 9 elements, which you’ll see in the colored squares above.

These three elements also ladder up into a dimension (it’s triads all the way up and down). An essay has three dimensions: idea, form, and voice. Ideas have centrality, form is about linearity, and voice is a texture.

Below, I’ll break down a strength and weakness of each dimension. You can follow Essay Architecture for detailed chapters on each of the patterns, but you can enjoy the write-up below without knowing the intricacies of the system.

Sontag has a bold thesis that challenges centuries of art and criticism, and it’s pretty simple: don’t interpret meaning, focus on form and experience. The essay is 4,019 words long, and not only is the thesis legible throughout the whole thing, but it’s supported by a stunning array of material.

Sontag died in 2004 with over 15,000 books in her NYC apartment. She was an avid reader, and this essay is a display of her encyclopedic knowledge. There are at least 49 separate examples she references, meaning she drops a new source, on average, every 82 words. Sometimes, it’s just a machine-gun list of name drops:

“Proust, Joyce, Faulkner, Rilke, Lawrence, Gide… The list is endless of those around whom thick encrustations of interpretation have taken hold.”

This might be an example where a strength and weakness are related. While the range is incredible, there’s no hierarchy. No one example was more important than the next. It’s missing a microcosm. The most detailed example is possibly about Kafka, but there’s no mention of him outside of this one paragraph:

“The work of Kafka, for example, has been subjected to a mass ravishment by no less than three armies of interpreters. Those who read Kafka as a social allegory see case studies of the frustrations and insanity of modern bureaucracy and its ultimate issuance in the totalitarian state. Those who read Kafka as a psychoanalytic allegory see desperate revelations of Kafka’s fear of his father, his castration anxieties, his sense of his own impotence, his thralldom to his dreams. Those who read Kafkas as a religious allegory explain that K. in The Castle is trying to gain access to heaven, that Joseph K. in the Trial is being judged by the inexorable and mysterious justice of God …”

While there is a thesis that unifies her material, there is no central example to give the mind an anchor in complexity. There are two options here: she could zoom into one artist (ie: Kafka), or, she could put herself onto the page.

As rich as her cultural knowledge is, Sontag isn’t a character in her own essay. I have limited knowledge about her life; I’m curious to know more, but this essay doesn’t reveal anything. I’m not implying she should veer into a confessional mini-memoir. I’m saying that even 3 paragraphs would round this out.

Why does Sontag feel this way about interpretation? What brought her to this conclusion? What motivated her to write this essay? She says that critics shouldn’t speculate on the motives of the author, but if the author isn’t vulnerable enough to share her motives, the reader will naturally wonder.

Might this essay have anything to do with the fact that in 1963—the year before Against Interpretation—she released her first novel, “The Benefactor,” to mixed reviews? Were critics putting words in her mouth? I don’t know, and it’s not my job to interpret. It’s her job to tell us.

The void of the personal dimension is common—sometimes mandatory—in journalism or academia, but this was published in a counter-cultural magazine (The Evergreen Review), alongside Beat poetry and experimental essays. The choice to leave herself off the page was a personal one.

Unlike her amazing sources—which another well-read intellectual could replicate—her own life is a reservoir of material that no one else has access to. Experience is the research that makes an essay uniquely yours.

This essay was a revelation to me on the second read, and to me that’s a hint that there’s an underlying problem with form. The introduction didn’t give me a frame to process the flurry of detail. What’s going on?

The essay is made up of 10 sections, and the sequence makes total sense. It starts back in ancient Greece, and moves forward through the Bible, the Enlightenment, and the 20th century. I outlined the structure below, so you can quickly see how she’s moving through material:

Origins: Since Plato, we’ve asked art to justify its own existence.

The problem: Art for the sake of interpreting it misses the point.

Why?: Historically, people used interpretation to fit old art into new agendas.

Consequence: The intellect devours art, creating a world of shadow meanings.

Examples: Works of genius aren’t seen directly, but as elaborate allegories.

Reaction 1: Some artists get self-conscious and try to control interpretation.

Reaction 2: Others escape interpretation through irony, abstraction & parody.

Solution: A better form of criticism would look at form instead of meaning.

The Desired Effect: We can recover our senses and the power of experience.

Call to Action: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.”

The problem is, I was blind to her thesis until section 7, and it wasn’t fully clear until 8. A better introduction would have laid the contours of her thesis. I’m not saying the essay needs to reveal her whole point of view upfront. There’s value in surprise. Save the full thesis for the conclusion. But she could have hinted that a better kind of interpretation exists without spoiling the details. This gives me, the reader, a goal (I anticipate the conclusion to learn her discovery).

So while the structure is solid, the storytelling is weaker. Structure and storytelling are opposing forces; one orients you, the other teases. Without opening loops or setting stakes out of the gate, the reader has to muck through a lot of detail without knowing why they should care.

One of my favorite quotes on writing is nested at the end of this essay.

“What is important now is to recover our senses.

We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.”

Those same three words (see, hear, feel) were also used by Joseph Conrad in 1897. Before I learned about either of these quotes, my voice dimension was structured with the same three elements: sight, sound, spirit. There’s something to it. Reading is abstract; and so prose wants to stretch itself to hit us at the level of our nervous system. This is why words want to sound musical off the lips, render hallucinations in the mind’s eye, and give you the chills up and down.

As well as she articulates this, I wouldn’t call this essay a sensory experience. There are a few moments when the ears and eyes turn on. (She’s great with repetition. She’s great with subtext. Not only is she good with imagery, but she weaves motifs of shadow and smoke through the essay.) Still, the default tone of this piece is dense and academic.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with academic writing; in fact, I think much of the essays I read could use more research, rare words, and abstract concepts. The problem is in the density. Try reading these two sentences out loud to hear what I mean.

“Even in modern times, when most artists and critics have discarded the theory of art as representation of an outer reality in favor of the theory of art as subjective expression, the main feature of the mimetic theory persists. Whether we conceive of the work of art on the model of a picture (art as a picture of reality) or on the model of a statement (art as the statement of the artist), content still comes first.”

There are too many multi-syllable words in a row, and too many abstract words per sentence. The Flesch-Kincaid score—which is a metric for readability—puts this at an 18th grade reading level (for context, this essay is at a 7th grade reading level). Sontag’s sentences are all extremely precise, but at the expense of rhythm, rhyme, concision, and tone.

Despite some occasional elegance, this essay is work to read through. Similar to philosophy writing or architectural theory (the worst of the worst), it assumes and demands a lot from the reader.

Some might argue that this is intended for an erudite audience, but I’d argue that this attitude is laziness. An essay can simultaneously appeal to experts and beginners, the in-crowd and the out-crowd. If she slowed down and rendered her abstract concepts in more sensory terms—which is the exact solution she calls for—it would speak to both groups. Sensory prose is more legible to newcomers, and it transcends jargon and cliche to create a novel experience for even the most well-versed art critic.

Against Interpretation is a historically important essay, with a powerful and well-backed thesis. Her call for a “dictionary of forms” resonates with me, and it’s an idea I’m personally acting on. I wouldn’t be surprised if much of my thinking stems from her influence (maybe my architecture professors read Sontag). I see my project as an extension of her call to analyze what art is rather than what it means.

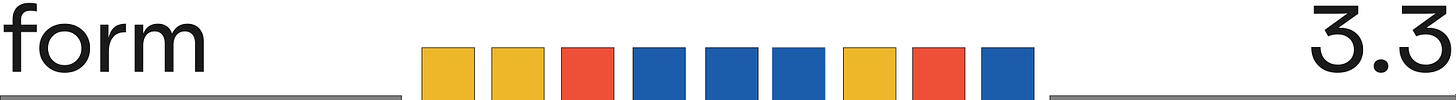

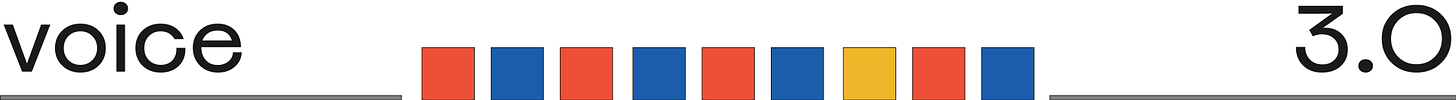

All that said, in terms of the formal quality of this essay, I’d say that it’s middle-of-the-pack “good.” I give it a 6.2 out of 10. This is not as bad as it sounds. It is not an F, it’s a 3.3 out of 5. While certain patterns are profoundly good, this score is a proxy for “formal completeness.” It’s a measure of how well-rounded it’s doing across all of the formal moves I’ve seen across the essays I’ve read.

The lack of a personal narrative, paired with her dense prose, creates some distance. I’m curious to learn more about her ideas and life, and will keep reading her essays in search of other sides of her craft (open to recommendations!).

While I think it’s helpful to study and edit form from an analytical lens, it’s all for the sake of creating and consuming from a place of the immediate, the felt, and the seen. We use the mind to transcend the mind. It’s worth studying form so that we can poke into the realm of the weird, the mysterious, the strange, the confessional, the experimental, and still make sense. She says, “good art has the capacity to make us nervous.” I’ll close on the opening line of her essay:

“The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory magic; art was an instrument of ritual.”

Let’s riff:

What did you think of Against Interpretation?

What’s your main takeaway from this review?

Any feedback on the format of this?

I waited until I had the time and attention to focus on your essay properly, Michael (I'm not fooled by the modest amount of time Substack calculates is required to read and understand one of your pieces!)

This is a great worked example applying the Essay Architecture metrics. You demonstrate their value very well in your assessment of "Against Interpretation". Sontag was always an inexplicably over-valued intellectual and you've crisply and objectively established the merits and demerits of her iconic essay.

Reading it made me realize I STILL haven't allocated enough time to fully appreciate your essay. I'm going to go back in the next day or two and click on all your links to refresh my understanding of each criterion, and the re-read the essay in the context of those clarifications.

What would be really helpful and cool would you videoing a lecture of yourself teaching your application of Essay Architecture to "Against Interpretation", popping up the meaning--with further examples--of each criterion, as you go. There's a lot to unpack in your methodology and a meta tutorial would be a great way to help readers fully appreciate your thinking.

Otherwise, the danger is a reader may breeze through your very deep thinking about each metric and not fully appreciate your achievement. I think the score for Sontag's essay is correct and unequivocally establishes the value of the Essay Architecture approach.

I want the author on the page btw. Anything else is pretentious.