My essay from Wednesday — Margin Matchmaker — went through 17 revisions (with 10 different editors). It sounds excessive for a writer to do this, but it’s a pretty standard method for comedians1 and songwriters. It’s a form of 'social writing.'

The default mode of writing is ‘solo-mode.’ Writers type the keys. Readers swipe the screen. Their communion is async, happening in margins and comments sections. To understand social writing, maybe it’s worth learning from artists that iterate in front of live audiences.

They tweak their material based on reactions from the crowd. They perform the same ideas over and over, to fresh audiences, tweaking it slightly (or radically) each night. Gig to gig, the material gets tighter. Based on the laughter or silence from the night before, the set mutates. Its form, tone, and delivery evolve based on feedback.

Check out this 3-minute video on how a comedian refines the same joke over three sets. At the end, Mike Lawrence says: “The beauty of a place like New York is you can bomb really hard, but you always know the next show is so close.”

Comedians get back-to-back chances to test their material. If they iterate, they’ll discover the best way to deliver an idea. It takes time, but it leads to battle-tested, refined jokes. Best of all, it brings a degree of certainty. They know how their material will land on virgin ears. Only when it can reliably make a crowd roar do they freeze it into permanent recordings.

So how can online writers “road test” their material? We can change feedback from a one-time event to a string of opportunities. I’m still ironing out this process myself, but here are three concepts that are starting to crystallize:

Flash Feedback — the way to ask for feedback

Color Maps — the way to implement feedback

Reader Circuits — the way to test your edits

Flash Feedback

Comedy might be the hardest of the arts. The real-time reaction of the crowd is an sharp reflection of the material. Laughter is an instant, unmistakable, and involuntary signal. This format makes comedy excruciatingly vulnerable, but also rich in feedback.

Feedback is more elusive for online writers. Most people read without engaging. Some like, and fewer reply. Comments are usually a reflection on the whole piece, not the bits. Unlike the comedian, you’re deaf to laughter. There’s no granular feedback at the sentence level. Unless you ask for it, you won’t know how your paragraphs are landing.

Recently, I’ve been asking my editors for “flash feedback.” I basically want micro-reactions — a high frequency of low-resolution comments. I want them to turn off their Editor Brain, and slip into the mind of a “reader in the wild.” Give me gut reactions. Be unapologetic. What is your first impression of this string of letters?

I encourage my editors to give me “binary reactions.” Put simply, is each part ‘good’ or ‘bad’? This can happen in a few ways:

You can use a (+) or (-) sign.

You can use simple grunts that indicate (+/-), like “whoa, lol, amazing, interesting, YES” or “confused, meh, boring, lame.”

You can use emojis 👍.

By making it easy to give flash feedback, you get a higher density of reactions.

I want to know which moments pierce the page. I want to know where I land and where I bomb. Flash feedback not only lets me read the crowd, it lets me know where to edit.

Color Maps

By turning my editor’s reactions into colored-highlights, I get a visual ‘color map’ — it’s a proxy for how my ideas were understood.

Every editor gets a ‘personal copy’ of my master doc. They should be uninfluenced by the reactions of others. If two readers independently highlight “whoa” on a sentence — that’s a great sign. There’s a pattern. It’s likely to trigger a reaction in future readers too.

Once they’re done, I’ll open my ‘master doc’ (in Notion) alongside it. I read through their comments, and highlight the master doc sentences in either green or red.

As I go through multiple rounds, I start to build a dense color map. It’s like a heat map that shows how each sentence is performing. In one glance, I can see where the dopamine wells are, and where the knots are. Instead of guessing where I should start editing, I just follow the colors.

First I address the reds — anything red is obviously not working. I either rewrite the paragraph, move it, or delete it. It's an obvious area of tension, and should be addressed before any optional tweaking.

Then I look at the blank spaces — If there were 4 paragraphs of straight slog, what's going on? Could I slay the technical jargon and use a metaphor? I'll examine and compress any dry patches. Each paragraph has to carry its weight — whether it’s an insight, a personal confession, or a splash of humor. If multiple people gloss over a stretch of text, the essay isn’t tight enough. The goal here is density.2

Finally, I check out the greens — What is working well? If multiple people liked something, then maybe it’s worth drawing extra attention to it. I’ll break these moments into their own paragraph, and sometimes I’ll even bold it and 2x the font size.

Reader Circuits

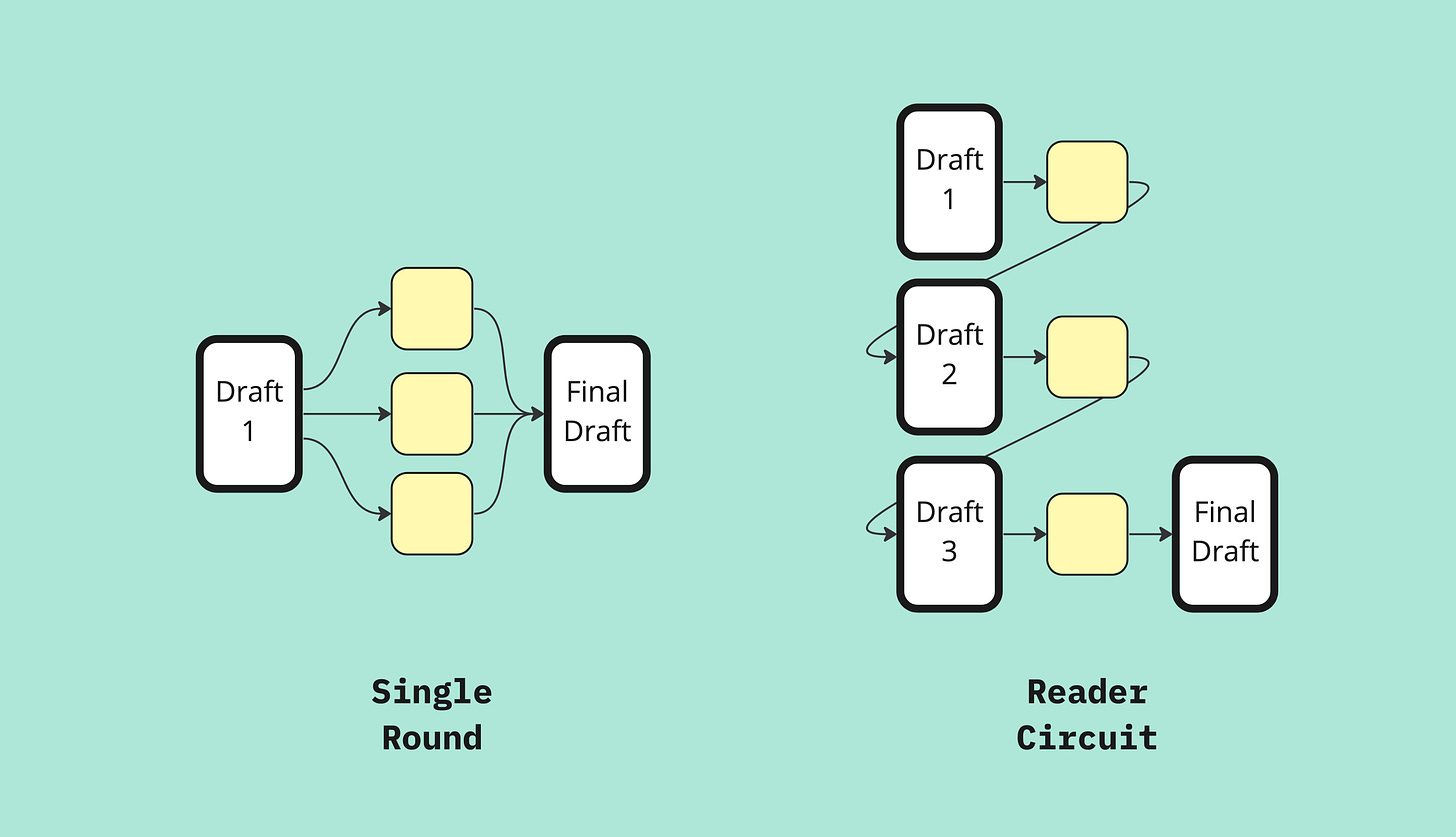

When we have a draft that’s ready to go, we’ll often share it with everyone who’s up for an exchange. This is the norm in group chats and public forums. You get a chorus of perspectives, incorporate it all, and ship it.

What if it’s actually better to show it to one person at a time?

When you gather all your feedback in a single round, you don’t get to test your edits. There’s an element of guessing. Maybe 3 different readers each point out the same hole in your essay, and offer their own idea on how to fix it. You can pick one, but you won’t know how the revision lands on someone with fresh eyes.

Instead, we should use a “reader circuit” to get feedback.

Instead of sharing 1:many, share in a sequence of back-to-back 1:1s. Start with one person, get feedback, make the edits, and then test those edits on a fresh reader. Repeat as often as you need. By looping this process, and moving through a reader circuit, the draft reaches higher levels of clarity.

This is how comedians do it. They run their new set dozens of times in underground venues before they perform in a high-pressure scenario. They repeat the same joke over and over, across different audiences, until they have certainty. If the idea or delivery isn’t working, they’ll either tweak or cut.

How many loops do you need? It depends. Margin Matchmaker had 17. The 1,000 Day Molt only had 3. If you don’t set a deadline, you can tinker into oblivion. My goal is to fit as many cycles as I can within my interval (whether that’s weekly or monthly).

Eventually, the color map will tell me when to stop editing. When there’s no white-space, and at least one green highlight per paragraph, it’s ready to publish.

These 3 ideas point to the power of social writing. Flash Feedback, Color Maps, and Reader Circuits can’t be done on your own. It all comes down to having a group of honest friends that enjoy wrestling with early-stage ideas. They react, they contribute, and they show you your blindspots. Friends are the secret to delivering ideas at their peak form.

Happy Sunday.

U P D A T E S:

I published an essay called Margin Matchmaker on Wednesday. Imagine drafting a sentence, and then suddenly an excerpt from your unread library pops into the margins. It’s like a telepathic second brain. This looks into an AI use case for writers outside of the killer chatbot paranoia.3 Today, I’ll deconstruct the process on how I wrote this.

It’s been a week of racquet sports. It started with virtual reality ping pong,4 and ended with two games of racquetball.5 If you’ve never heard of it, racquetball was the pickleball craze of the 1970s. It’s like indoor tennis fused with handball and pinball — angular, fast, half-court, and 360 degrees. I joined a competitive league where I’m half the age of the next youngest player. I rarely win, but got my first W yesterday.6

Greek Orthodox Lent started a week ago. I haven’t done the fast in 8 years, but there’s a few reasons why I’m giving it a shot.7 It’s inspiring me to write and publish some of my long-held ideas around Christianity. They’re unorthodox, borderline heretical, but well-intentioned. Next Wednesday, I’ll publish an essay called “Resurrections On-Demand.” It’s about how Christian rituals evolved from an Ancient Greek ceremony that used psychedelics.

L O G S:

I recently learned how to use anchor links in Substack (every header has one). By clicking on a link below, it shoots you into an exact point in my February logs. Instead of copying logs into these Saturday updates, I’ll give you a link menu (single source of truth FTW).

Let’s riff:

What are the pros/cons of your current feedback process? Are you considering any of the ideas from today’s Deconstructed issue?

How did the menu of logs work? Should I link out to the source log, or copy a few into the issue instead?

Permission to go on random tangents about racquet sports, virtual reality, religion, and AI.

Footnotes:

On the day I published my essay, OpenAI released their API for Chat GPT. This lets developers build AI into their apps, and link it with data from other places. Dan Shipper already built a ‘writing copilot’ that can analyze a new paragraph, and match it with a quote from his Readwise.

Let me know if you have a VR headset, and we can play Eleven Table Tennis.

Here’s another first-person video from last week that includes some racquetball footage.

a) It aligns with my molt date. b) Beautiful church within walking distance of my new place. c) I’ve been wanting to take Sundays off. d) Psychological discipline and revival. e) Being a part-time vegan is good for a meat-eater.

I can’t speak to the craft of comedy from direct experience, but if you want that first-hand take, check out The Comedian’s Guide to Feedback by Raza Jafri.

Check out Seeking Density in the Gonzo Theatre, by Venkatesh Rao.

One strategy is to share your draft with someone new after each session. It’s a good forcing function. You end up getting your draft to a readable place. The challenge is syncing up with others (they have to be available, and you need to be able to give them feedback on their draft too).

Congrats on your racquetball dub!

I love the idea of reader circuits. You’re right that the feedback you get on a published piece is usually high-level, rarely granular. To allow myself additional iterations on a piece, I’ll revise and republish my essays. (I override the post and leave the old version up as a nested page.) That way, revision doesn’t stand in the way of publishing, and I can return to the piece after months, with fresh eyes, to tear it up. That practice has helped me solidify my style and spot my weaknesses.

But what do we do if we don't have any honest friends? jk I think...

...thanks for the inspiration...they say it takes a village and I have definitely found the more eyes and minds touch my ideas the more thoughtful/polished/balanced they become...the work is never done...

...on the AI front I haven't experimented yet, but getting THE MACHINE to help criticise content by using different voices and mindsets could be a useful way to do this if you got no one around...or you could just do what I do and show the computer to your dog...if the dog licks it I have comedy gold...if the dog turns on me instead it is back to the old writing board...I've found it helps to always cover your computer in peanut butter for this editing approach...