Links:

“Here is New York” (1949) online

Essays of E.B. White (1977) print collection

If anybody ever questions me on how an essay can pack the punch of a book in a sliver of space, I might point them to E.B. White’s “Here is New York,” something I read in 30 minutes while waiting outside a tortaria south of Union Square, something that changed my lens to the place I was sitting, the city I was born in.

If you haven’t heard of White, you likely know his classic children’s books on animals going rogue (Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web). If you have heard of him, maybe it’s from Elements of Style; I was required to buy this 43-point manual in my freshman writing class, but knew nothing of its Cornell authors or that it sold 10 million copies.

Chances are, you haven’t read an essay of his. I hadn’t until June.

In over 50 years at The New Yorker, he published hundreds of essays, all of which were relatively eclipsed by his breakouts. You can sense a mild frustration in his letters. In the opening to his 1977 essay collection, he says the essayist is a “second-class citizen” destined to “ramble about” through the pleasure of an “undisciplined existence.” Any writer with their sites on “the Nobel Prize or other earthly triumphs had best write a novel, a poem, or a play.” A year later, they gave the man a Pulitzer Prize for his full body of work. It was in the special awards category. His essays were too good to ignore, but there was no formal way to acknowledge them.

I’m surprised I never heard of “Here is New York,” not only because I’m a native and it’s arguably his most famous essay, but because it surged in popularity after 9/11. He wrote this on a visit during a hot summer in 1948, ten years after he left the city and moved to Maine, and three years after the war ended. Kamikaze attacks and atom bombs were still fresh in the public’s consciousness; annihilation loomed. He covers the mysteries of the city, how it’s changed, and a new paranoia that the whole thing could be destroyed by a “flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese.”

In the opening few pages, I experienced the most chills-per-page among anything I’ve read this year. Unlike the very technical Elements of Style, whose opening line is “Form the possessive singular of nouns by adding ‘s,” this is the master at work, amalgamating all those pesky grammar rules into a string of words that would outlive its author and speak to the broken heart of a grieving city.

Yet, towards the middle, something slogged.

The ending redeemed itself, but the dip in the middle was significant enough to break my initial reader’s trance. It happened again on my second read, and after five reads I think I know why: a structural hiccup.

The spirit of this project is to review the formal qualities of an essay. Forget the history, forget my affinity for the city; how is it working as a composition?

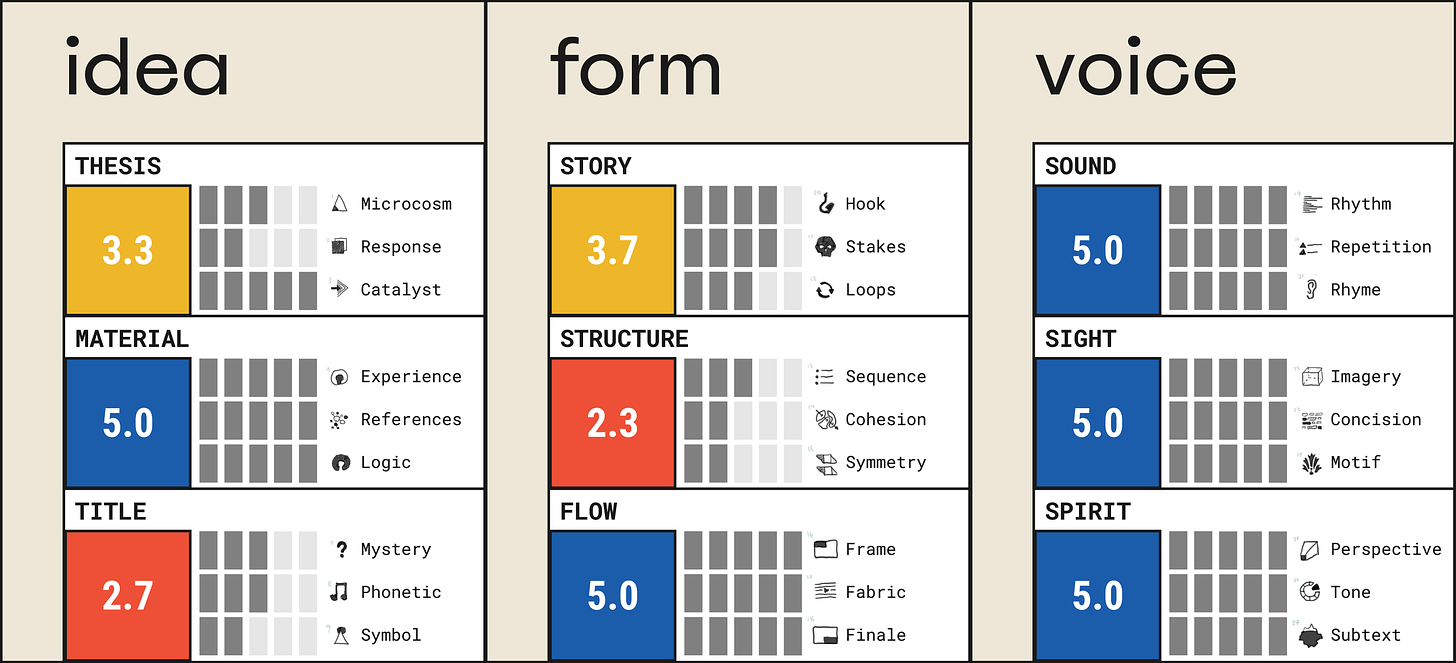

So how does this work? There are 27 “patterns” that I score 1-5, which you can see in the gray rectangles above. These patterns are in groups of 3—called “elements”—which you can see in the 9 colored squares above. Elements ladder up into a “dimension,” of which every essay has 3 (idea, form, voice). The post below is organized to highlight a strength and weakness of each dimension. All scores are out of 5.0, but at the end I convert the score to be out of 10.0.1

This essay is a masterclass in Material. It’s called “Here is New York,” as if a thing is being formally introduced to you, but it’s nothing like a bus tour. It isn’t a landmark-fest, it’s a lucid impression through the prism of the author’s mind. Sure, he mentions the Empire State Building, not as a marvel of engineering, but as the “white church spire” of the nation, one that people happen to jump off, causing pedestrians to “quicken step.”

In terms of Experience, White weaves his biographical details, his perceptions of chaos, and his inner perspective on the strange and changing city. It’s an essay only he can write.

We start in the Algonquin Hotel on 47th street in 90-degree heat. He reflects on his past, to the time he was an usher at the Metropolitan Opera, and to the time he was a young writer in NYC looking up to the “stable of giants.” He takes us on strolls around Manhattan, rendering parks, buildings, festivals, strangers, the homeless, and the time he sat 18 inches away from Fred Stone, the lead actor of The Wizard of Oz.

In terms of References, he shows us historical events of literary significance that happened in NYC (like the exact location where Hemmingway hit another writer across the face with a book), timely events from a 1948 newspaper (like airs shows, a lion convention, a spousal murder, and death by falling cornice), and good old stats (racial breakdowns, geography, and a romanticization of Con Edison logistics).

If you want to see an epic run-on sentence that shows off his range and density of Material, check out this footnote.2

Though he never quite unifies all his material into a Thesis, you can sense it in the opening paragraph. New York gives you “the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.” He also says, “it can destroy an individual, or it can fulfill them.” New York is filled with paradoxes. The things that make it amazing simultaneously make it terrible.

Some sections gush like a love letter to the city:

“A poem compresses much in a small space and adds music, thus heightening its meaning. The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines. The island of Manhattan is without any doubt the greatest human concentrate on earth, the poem whose magic is comprehensible to millions of permanent residents but whose full meaning will always remain elusive.”

Other sections unleash apocalyptic paranoia:

“The subtlest change in New York is something people don’t speak much about but that is in everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions. The intimation of mortality is part of New York now: in the sound of jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest edition.”

This dual nature runs throughout the essay, but (a) it fades in and out, (b) the dots are rarely connected out loud, (c) it isn’t put in context, and (d) it isn’t unified under a single symbol. The essay is brimming with images, and many of them could have served as a microcosmic anchor: the willow tree? The lion convention? The Empire State Building? Without hierarchy, each metaphor occupies its own block, and the soup of scenes leaves us without a souvenir.

Keep the chaos, but give us a frame.

While there is a thesis brewing, it didn’t make it into the title. The title is an opportunity to compress the essay into a small, spreadable meme that gives the culture language for the unnamed. The popular phrases that have become cliches in New York’s lexicon (“the big apple,” “the city that never sleeps”) were coined in articles and movies from the 1920s. White may have captured the soul of an American city better than any other piece of literature, but he didn’t name it. “Here is…” sounds like a travel brochure series for tourists. It doesn’t help the reader enter or exit the essay with White’s specific slant. It doesn’t tap into his rich ideas— on privacy among crowds, on forced cooperation, on how a system that breeds peace invites destruction—all of which ladder into “paradoxes of density,” a theme that his title could have embodied.

“Make the paragraph the unit of composition.”

This line from Elements of Style always stood out to me, and so what better occasion than this to analyze E.B. White’s paragraphs?

Paragraphs matter. I’ll always resist copywriters who insist that paragraphs should never be longer than 1-3 sentences. According to White, each paragraph should contain an indivisible topic. Every paragraph functions like a scene change, a visual aid to let your reading know you’re shifting from one facet to another. If you use paragraph breaks too liberally, your reader won’t see the seams of your thinking.

There is no right answer for how long a paragraph should be; White says they can range from “a single, short sentence” to a “passage of great duration.” What is more important than length is rhythm. Similar to how sentences jump between S,M,L, paragraphs do the same.

The image below shows every paragraph in “Here is New York” as a blue line. Read the right edge. It’s breathing. His longest paragraph is 10x longer than his shortest.

His average paragraph is 15 “lines” (an obviously imprecise unit—I have a physical book and no access to copyable digital text, so all I could do here is count how many vertical lines a paragraph spanned. Yes, tedious.)

If you go one standard deviation above and below 15, you can see how he’s oscillating between 7 and 23 lines. Notice how whenever he stretches into the 30s and 40s, the next sentence always craters down to below the average length? After you fry your reader’s brain with an epic wall of text, they need a minute to recharge. But rhythm is more than just stamina; it mirrors content. The longer paragraphs are fireworks of exposition, where he’s rendering Material in high-detail. The shorter paragraphs are used for transitions and—as quoted from Elements of Style—“to indicate the relation between the parts.”

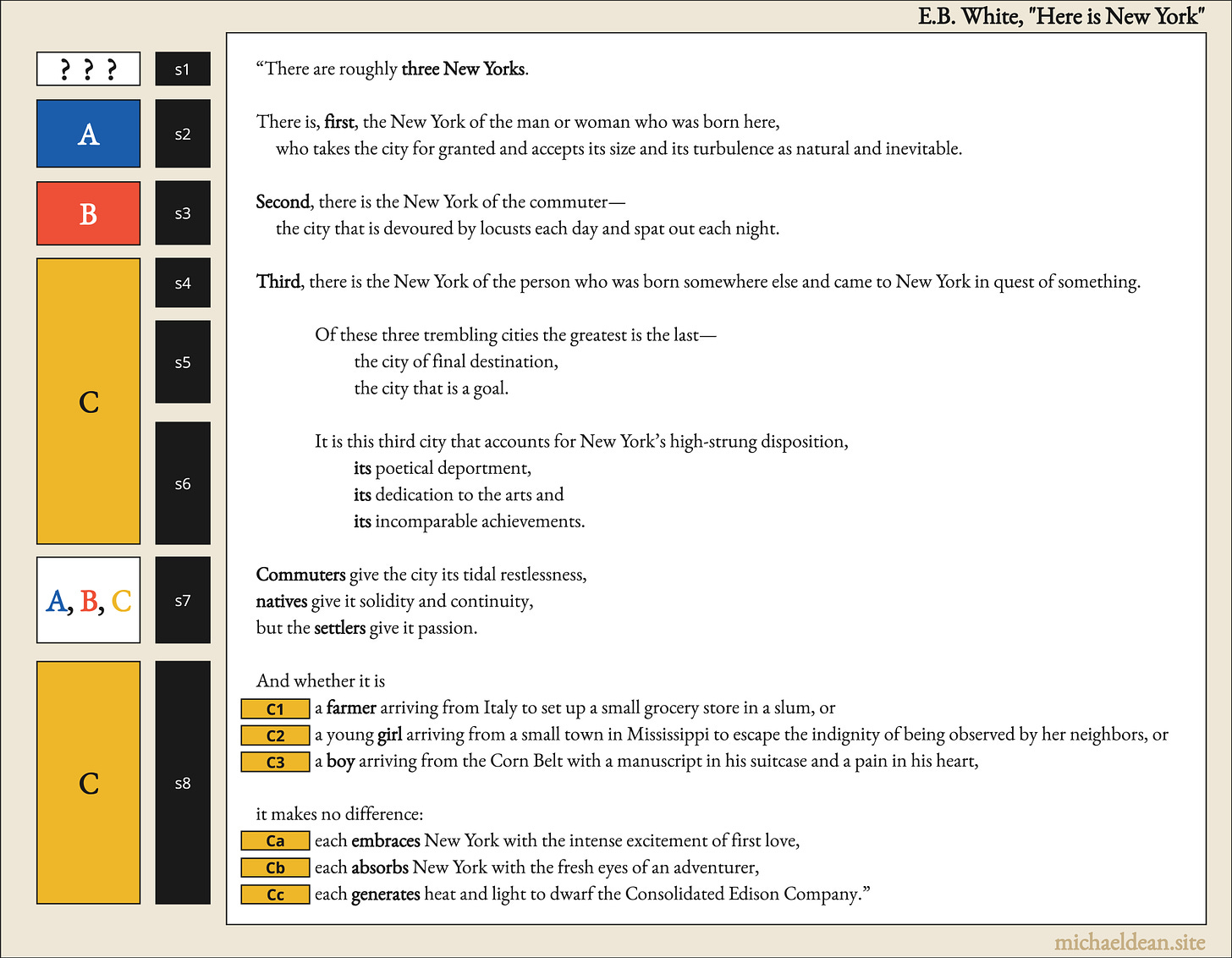

Let’s break down one of his bigger, better paragraphs (8 sentences, 22 lines in print).

When you read it as a block of text, it seems loose and flowing, but when you break it down you can see its obvious form. In case you want to read it in its pure, block form, it’s here in the footnote.3 ( And if you’re on mobile, click the image and switch to horizontal).

Here are some compositional ideas from this paragraph that you can experiment with in your own writing:

Minimal frame / maximal finale: Notice how the topic sentence—the “Frame”—is dead simple: “There are roughly three New Yorks.” In 6 words he sets the topic and opens a loop for a 243 word paragraph. It is a 40x act of compression. The closing sentence—the “Finale”—is long, 40%-of-the-whole-paragraph long, and in contrast to the categorical opener, it ends on a poetic notion: “[They] generate enough heat and light to dwarf the Consolidated Edison Company.” This aligns with my maxim, simple topic sentences enable insane paragraphs.

Looping through objects: The paragraph, at its core, is a set of objects that he loops through multiple times at different scales of detail. First (in Sentence 1, s1) he tells you there are three New Yorks, without any hint as to what they are. Loop opened. Then, he goes through them one by one: A (s2), B (s3) , and C (s4-6). Then he puts them all in one sentence to summarize the role of each (s7). He closes by unpacking C in a long sentence with two list (s8).

Telescoping triads: Notice how he uses threes all the way down? 1) There are three types of New Yorkers. 2) The third type (C), the type he’s most excited about, gets three sentences (the third of which is, BTW, a list of 3), while the other types (A,B) only get one. 3) After he summarizes the three types, he returns to C and picks two parameters (examples of the people who come to New York, and the actions they take), and expands each of those into their own triad that gets nested in a list sentence.

There are multiple paragraphs throughout the essay with this level of elegance.

If “micro-structure” is the design of an individual paragraph, then “macro-structure” is the design of the essay’s arc—in this case, a sequence of 46 paragraphs. Mastery at the micro-scale can dazzle the reader, but enough meandering at the macro-scale will get them lost. Marco-structure is outside the scope of Elements of Style; the only advice it gives is, “Choose a suitable design and hold to it.”

What makes a suitable design? Can you really know a suitable design before you start? At what point do you have to let go of your original skeleton?

E.B. White nails the beginning and the ending, but the middle feels like a random flash of vignettes. He even explicitly admits this. At the beginning of “section 3,” he starts by saying, “I wander around, reexamining this spectacle, hoping that I can put it on paper,” and that’s exactly what this feels like: a Saturday scroll, printed chronologically,4 in high-resolution, but incohesive and unrelated to the paradoxes of density.

My simplest structural suggestion would be to cut Section 3 altogether (paragraphs 22-30) and then rewrite Sections 4 and 5 (paragraphs 31-41). Sure, this involves killing some beautiful paragraphs, which I’d feel bad about if the first 20 paragraphs weren’t some of the best I’d ever read. Just because something is elegant in its micro-structure, doesn’t means it gets a pass from the macro sledgehammer.

For a more detailed restructure, I would: 1) propose a simplified 4-part outline, 2) show how to shift existing paragraphs into the new structure, and 3) note what could be cut, refined, expanded, and connected. (Obviously—and especially if you haven’t read the piece yet—don’t feel like you need to fully grasp the edit below.)

Maybe it takes an organic mind to generate the first stream of 46 paragraphs, but it takes a surgical mind to find patterns and rewire the parts. FWIW, I’m against pre-configured templates. I don’t think you should know your design before you start. Let it emerge—mangled and unpredictable—and then from the heap on the page you can start your puzzle.

I gave this essay a perfect score in the voice dimension, which isn’t surprising since this comes from the guy who literally revised the book on style. Every element is in full force.5

Since “Here is New York” gave me the chills throughout, I wanted to focus on the element that—I think—is most responsible for that: imagery. Strings of words are processed in the mind, but when those words can be viscerally seen, they buzz through your nervous system. There are many platitudes around imagery (ie: show, not tell), but White isn’t just showing detail, he’s using specific, sophisticated moves that come together to make this essay feel like a hallucination.

Use quantities to convey awe.

Over half of the paragraphs include numbers, scale, and volume. He’s not just saying “big,” but he’s giving a precise value so you get the nature of how big. This is perfect for New York, where the line between reality and hyperbole is already blurred. Here are 5 examples out of several dozen that were tough to exclude:

Astronomics: “It is a miracle that New York works at all. The whole thing is implausible. Every time the residents brush their teeth, millions of gallons of water must be drawn from the Catskills and the hills of Westchester.”

Relative size: “New York is nothing like Paris; it is nothing like London; and it is not Spokane multiplied by sixty, or Detroit multiplied by four.”

Unit swapping: “Irving Berlin’s journey from Cherry Street in the Lower East Side to an apartment uptown, was through an alley and was only three or four miles in length, but it was like going three times around the world.”

One big thing vs. many small things: “… New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along (whether a thousand-foot liner out of the East or a twenty-thousand-man convention out of the West) ...”

Number and metaphor: “About 400,000 men and women come charging onto the island each weekday morning, out of the mouths of tubes and tunnels.”

Turn images into metaphors.

This essay includes dozens of images and dozens of metaphors,6 but the special moments are when real images get warped into metaphors by the imagination. It creates a dream-like effect; the thing that was real becomes fantasy.

Check out how “the fisher” mutates in this paragraph (on the NYC desk worker):

“He is desk-bound, and has never, idly roaming in the gloaming, stumbled suddenly on Belvedere Tower in the Park, seen the ramparts rise sheer from the water of the pound, and the boys along the shore fishing for minnows, girls stretched out negligently on the shelves of the rocks; he has never come suddenly on anything at all in New York as a loiterer, because he has had no time between trains. He has fished in Manhattan’s wallet and dug out coins but he has never listened to Manhattan’s breathing, never awakened to its morning, never dropped off to sleep in its night.”

Notice the bold. The <loiterer> will see boys actually fishing in Central Park, but the <worker> only fishes figuratively in Manhattan’s wallet. The Cartesian Object (the thing seen in real 3D space) becomes a Dream Object. The image shifts planes to form a creative analogy between two characters.

He does this all through the essay, but the most memorable one is when he starts with a literal NYC lion convention, and then transposes that onto a smaller American city getting ravaged by metaphorical lions (too long to share, so I put it in a footnote).7

Spread meaning with motifs.

In the third paragraph of this essay, which shows him sitting in the same restaurant as a famous actor, he uses the same phrase three times. He is loading an image (in this case, a quantity) with meaning, so that he can refer to it later:

“When I went down to lunch a few minutes ago I noticed that the man sitting next to me (about eighteen inches away along the wall) was Fred Stone. The eighteen inches were both the connection and the separation that New York provides for its inhabitants. My only connection with Fred Stone was that I saw him in The Wizard of Oz around the beginning of the century. But our waiter felt the same stimulus from being close to a man from Oz … before he could understand a word of English, he had taken his girl for their first theater date to The Wizard of Oz. It was a wonderful show, the waiter recalled—a man of straw, a man of tin. Wonderful! (And still only eighteen inches away.) “Mr. Stone is a very hearty eater,” said the water thoroughly, content with this fragile participation in destiny, this link with Oz.”

Now we associate this distance, “eighteen inches,” with the claustrophobia of a crowded restaurant, where citizens of all types are forced into contact with each other. When he uses this phrase later on, he reminds us of the whole lunch scene with just two words.

“The governor came to town. I heard the siren scream, but that was all there was to that—an eighteen-inch margin again.”

“Behind me (eighteen inches again) a young intellectual is trying to persuade a girl to come live with him and be his love.”

A motif—a repetitive visual element—isn’t merely decorative, it is a circulation system for meaning.

White isn’t just “showing,” he’s turning imagery into a syntactical language: he primes symbols and reloads them later, he—in psychedelic fashion—bends real sights into haunting metaphors, and he gives us quantities so we can feel everything he shows us in relation to our own body.

“Here is New York,” is an example of why essayists should be first-class citizens.

Don’t let an 8.0 fool you, this might be my favorite essay. As an editor/writer, I think there are ways to tighten the structure and scope of the idea. But as a reader, and—more so—as a New Yorker, this one hits me in a way that taps into decades of my own experience. In the end, this is what matters. Even if a writer achieves “formal perfection,” every reader walks away with their own unpredictable reaction. Still, composition matters. It is a delivery mechanism, and when it’s done right it becomes invisible. By sculpting ideas with extreme care, they move through the reader’s veins with no confusion and max potency, letting them come to their own conclusions at a personal, historical, or moral level.

I read this one in a physical book, “Essays of E.B. White.” It has 33 essays in it. Based on Amazon reviews—an imperfect metric—his collection only gets 5% of the attention of Elements of Style; this should be its required companion. Here are the elements of style at work. Anyone looking for inspiration in ways to stretch their writing voice should absolutely buy this book.

I’ll close on this quote from the back cover:

“His voice rumbles with authority through sentences of surpassing grace. In his more than fifty years at the New Yorker, White set a standard of writerly craft for that supremely well-wrought magazine. In genial, perfectly poised essay after essay, he has wielded the English language with as much clarity and control as any American of his time.”

Let’s riff:

What did you think of “Here is New York”?

What’s your main takeaway from this review?

Any feedback on the format of this?

Footnotes:

Scoring system: Since somebody asked in the last review, here’s my formula to convert scores from a 1-5 to a 1-10 (it’s not simply doubling it, otherwise a blank essay would get a 2 out of 10). An essay has a min score of 27 (all 1s) and a max score of 135 (all 5s). Here’s the conversion: (((Score-27)/108)*9)+1).

Run-on with dense material:

“I am sitting at the moment in a stifling hotel room in 90-degree heat, halfway down an air shaft, in midtown. No air moves in or out of the room, yet I am curiously affected by emanations from the immediate surroundings. I am 22 blocks from where Rudolph Valentino lay in state, 8 blocks from where Nathan Hale was executed, 5 blocks from the publisher’s office where Ernest Hemmingway hit Max Eastman on the nose, 4 miles from where Walt Whitman sat sweating out editorials for the Brooklyn Eagle, 34 blocks from the street Willa Cather lived in when she came to New York to write books about Nebraska, 1 block from where Marceline used to clown on the boards of the Hippodrome, 36 blocks from the spot where the historian Joe Gould kicked a radio to pieces in full view of the public, 13 blocks from where Harry Thaw shot Stanford White, 5 blocks from where I used to usher at the Metropolitan Opera and only 112 blocks from the spot where Clarence Day the Elder was washed of his sins in the Church of the Epiphany (I could continue this list indefinitely); and for that matter I am probably occupying the very room that any number of exalted and somewise memorable characters sat in, some of them on hot, breathless afternoons, lonely and private and full of their own sense of emanations from without.”

Paragraph on the 3 kinds of New Yorkers:

“There are roughly three New Yorks. There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born here, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size and its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter—the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something. Of these three trembling cities the greatest is the last—the city of final destination, the city that is a goal. It is this third city that accounts for New York’s high-strung disposition, its poetical deportment, its dedication to the arts and its incomparable achievements. Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness, natives give it solidity and continuity, but the settlers give it passion. And whether it is a farmer arriving from Italy to set up a small grocery store in a slum, or a young girl arriving from a small town in Mississippi to escape the indignity of being observed by her neighbors, or a boy arriving from the Corn Belt with a manuscript in his suitcase and a pain in his heart, it makes no difference: each embraces New York with the intense excitement of first love, each absorbs New York with the fresh eyes of an adventurer, each generates heat and light to dwarf the Consolidated Edison Company.”

On rendering your walks in prose: This is a fun exercise to try. Spend 1 hour in your nearest city, jot down everything you see into your phone as chicken scratch, and later, weave it into prose in that exact order. I did this and published it two years ago (Jaywalking), but I consider it more like a drill in observation and in voice than a well-rounded essay.

[Cut paragraph] Every element (of voice) is in full force: At the level of syntax, there’s a blend of tight sentences and insane run-ons, a range of repetition devices, and paragraphs that open with clarity and close with a ring. At the intangible level of spirit, he incorporates, “eloquence without affectation, profundity without pomposity, and wit without frivolity or hostility.” The subtext makes you laugh, feel, and wrench. The tone is dynamic, shifting between lovers-in-the-park mode and masses-getting-cremated-in-subways mode. There’s awe, wonder, innocence, terror. He’s not locked into a style; he shape-shifts with the content.

An (incomplete) list of metaphors:

The Empire State Building as the white church spire of the nation.

Grand Central as temple turned honkey tonk from extra-dimensional advertising.

The New York charm as a supplementary vitamin to put up with claustrophobia.

The jewel of loneliness.

Radioactive cloud of hate.

Planes no bigger than a wedge of geese.

The old willow tree as a symbol for a fragile vertical structure.

The lion convention paragraph:

“Since I have been sitting in this miasmic air shaft, a good many rather splashy events have occurred in town. [... 3 examples …] The Lions have been in convention. I’ve not seen one Lion. A friend of mine saw one and told me about him. [ … 2 more examples … ] A man was killed by a falling cornice. I was not a party to the tragedy, and again the inches counted heavily.”

“I mention these merely to show that New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along … without inflicting the event on its inhabitants, so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to choose his spectacle and so conserve his soul. In most metropolises, small and large, the choice is often not with the individual at all. He is thrown to the Lions. The Lions are overwhelming; the event is unavoidable. A cornice falls, and it hits every citizen on the head, every last man in town.”

I had no idea he was the white in "Strunk & White"! Also had to get it for freshman english

Loved this, incredible analysis. Some favorite lines:

“…and the soup of scenes leaves us without a souvenir.

Just because something is elegant in its micro-structure, doesn’t means it gets a pass from the macro sledgehammer.

By sculpting ideas with extreme care, they move through the reader’s veins with no confusion and max potency.”

So well written. The review especially resonated with me having already read the essay (per your rec). Agreed about his style being a perfect score, it was a joy to read it.

In terms of the review format — some of White’s best work is highlighted midway through (scale to convey awe, use of imagery. What if you brought a few top highlights to the very top of the next review, to give a sample of to your reader (especially those who haven’t read the essay being revered). Ex: the millions of gallons of water line is so good. Maybe you hook more people in to read the whole thing by sharing the best prose excerpts up front.

Reminds me of Scott Van Pelt, a star anchor at ESPN who now has his own name-brand version of SportsCenter that runs at midnight ET. Before any highlights or analysis he shares “the best thing I saw today” right at the top of the show. A funny, surprising or heart-warming clip that hooks people in. Then he gets to all the substance. It’s no coincidence his ratings are higher than the rest (one of many tactics he uses).

Starting off with the absolute best few lines of the essay could be your version of that.