“You’re looking for the Ur pattern of the essay…” said Jim O’Shaughnessy, clarifying my project to myself.

I first saw “ur” used as an adjective in a Lawrence Ferlinghetti poem1; it’s a German word for “archetypal,”2 but it also reminds me of the place. Ur was an ancient Sumerian city, the original city, the city that went on to shape all cities.3 It was where all the components of a civilization first intertwined: architecture, law, math, writing, religion, economics. It was a full-stack city.

I’d define an “Ur pattern,” then, as a stack of ancient components; they form an archetype that shapes every instance in a genre, even if we don’t easily recognize it.

“... And if you find it, it’s the mother lode.”4

Earlier this year I applied for an O’Shaughnessy Fellowship grant. The chances were something like 1 in 500, and although it may sound unlikely that a company with roots in quantitative asset management would invest in a writing textbook, I sensed there was a parallel. The opening line of my application—under the “unique insight” section—was a claim that is unorthodox in the writing community:

“Quality isn’t subjective, it’s statistical.”

Turning the Ur pattern into code_

For half-a-millennia, the medium of the essay has evaded classification, measure, and standards. This creates in-fighting and needless confusion, especially for new writers looking to learn.

I’m reading a book called Essayists on the Essay, which curates a 450-year async debate on WTF an essay even is, from Montaigne to Paul Graham. The opening line says, “the essay has yet to find its Aristotle.” It’s a mystery that no one has mapped the medium. The discord is clear in how Phillip Lopate—known for the “personal” essay—excluded Emerson and Bacon from his anthology. Some writers claim that their type of writing is all that matters. Other writers insist that essays are meandering streams of thought, allergic to rules.

Despite the radical range of essay types, and despite the wrinkles through history, culture, and readers, I sense there’s an Ur pattern under everything. Well, where does it come from? Why does it exist? You can find similar moves across all essays, not because of influence, but because every reader is human.

We all have limited bandwidth, we all read text linearly, and we all (generally) process reality through sight, sound, and emotion.5 Our neuropsychology matters; it invisibly shapes our constraints.

My goal is to unify the scattered schools of thought under a shared rubric.

I believe the essay is a unifier of opposites. An essay can be confessional and persuasive. An essay can be academic and psychedelic. It encompasses all corners of the human psyche. Whichever “type” of essay, it can be analyzed along a shared set of patterns.6

Quality is elegance across many patterns (more patterns than the mind can consciously hold at once).

This system is paradoxically objective and subjective. The Ur pattern is the universal archetype under everything, and your essay is a unique instance. It is an original work on ancient scaffolding.

None of these patterns are “new,” but no one has 1) assembled them into an hierarchical framework, 2) insisted that each one holds equal importance, and 3) created a scoring criteria so each one can be measured.

The real question: what is the best way to teach this? By next year I’ll have a 500 page textbook, but surely the best way to learn isn’t by cramming your head with rules. You learn by isolating one pattern at a time and practicing it through editing until it becomes second-nature.

But which pattern do you start with? (And how well can you articulate your own writing weaknesses?)

If there is an Ur pattern below the galaxaic range of essays, and if it were machine-readable, then any writer could use software to see their strengths and weaknesses. It would read your drafts and point you to the lessons you need to learn. This would give writers a path to bring their ideas to maximum, historic potency.

I applied for the O’Shaughnessy Fellowship, not just to finish my textbook, but to turn my philosophy of writing into code, and to elevate the quality of essays across the Internet. I heard back recently, and have an exciting update to share:

I won an O’Shaughnessy Fellowship Grant!_

I’m thrilled for this opportunity: it fuses the past threads of my life (architecture, technology, and writing), and it gives me the clarity, guidance, and resources to bring Essay Architecture into its fullest form.

Since 2020, my main goal has been—and still is—to master the essay. This next year I’ll dive deeper into the craft than I ever have, and distill what I learn into a product to help other writers. I’ve edited and coached and built courses before, but this can scale who I can help (if you’re one of the few who half-jokingly pitched that I turn myself into code, well then good news: Deanbot is happening).

What I’m building is quite different from the other AI writing apps you’ve tried. It’s not a chatbot. It’s not about automating your process, but guiding you on a life-long one. I’d rather alchemize minds than automate words. Jim made an elegant distinction in last Friday’s press release on the difference between AI doing the writing and AI helping the writer:

"Despite the influx of new and exciting technologies, writing—one of our oldest technologies—has remained as central to our civilization as ever, and while AI alone will never fulfill our need for great writing, it has the potential to be an incredibly valuable tool for the writers of the future.”

My product won’t write sentences for you. The slow process of writing is what clarifies thought, shapes identity, and cultivates a lens to the world. Writing is the whole point; it isn’t a chore to optimize, it’s an infinite game.

What I’m building is more like an editor turned into software. Think of it like Grammarly, but instead of neutering your prose through line-edits, it asks you profound questions that help you formulate Draft #2.

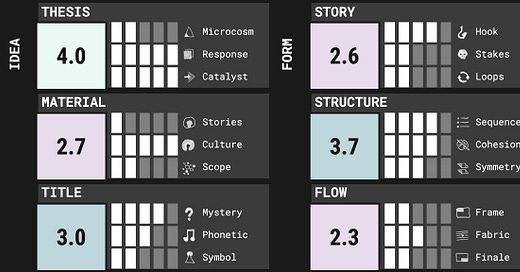

I want to give you a high-resolution mirror into your craft and draft. Imagine getting instant and thorough reports through a gDoc plug-in. Not only will it give you big picture feedback, but it’ll score your writing 1-5 across all 27 patterns. By clicking into a point, you’ll find paragraphs of feedback, examples, questions, resources, and exercises.

I’ve made a few of these reports for friends, manually. They take a few hours to make, and usually they’re 3x longer than the essay itself. People say it gives them clarity around the writing snags they’ve felt, but could never see or articulate. A year from now, I want to make this available to everybody in a single click.

The core technical challenge is making an AI editor reliable. Even though GPT-4o has binged trillions of words, it doesn’t inherently know the Ur pattern. As you probably know by now, AI will sometimes give you boondoggle.7 Even though ChatGPT can share feedback on your drafts—and is great for rubberducking8—it’s not exactly consistent (when I ask it to score essays, it acts like a random number generator).

Is it possible for AI to score essays as accurately as I do?

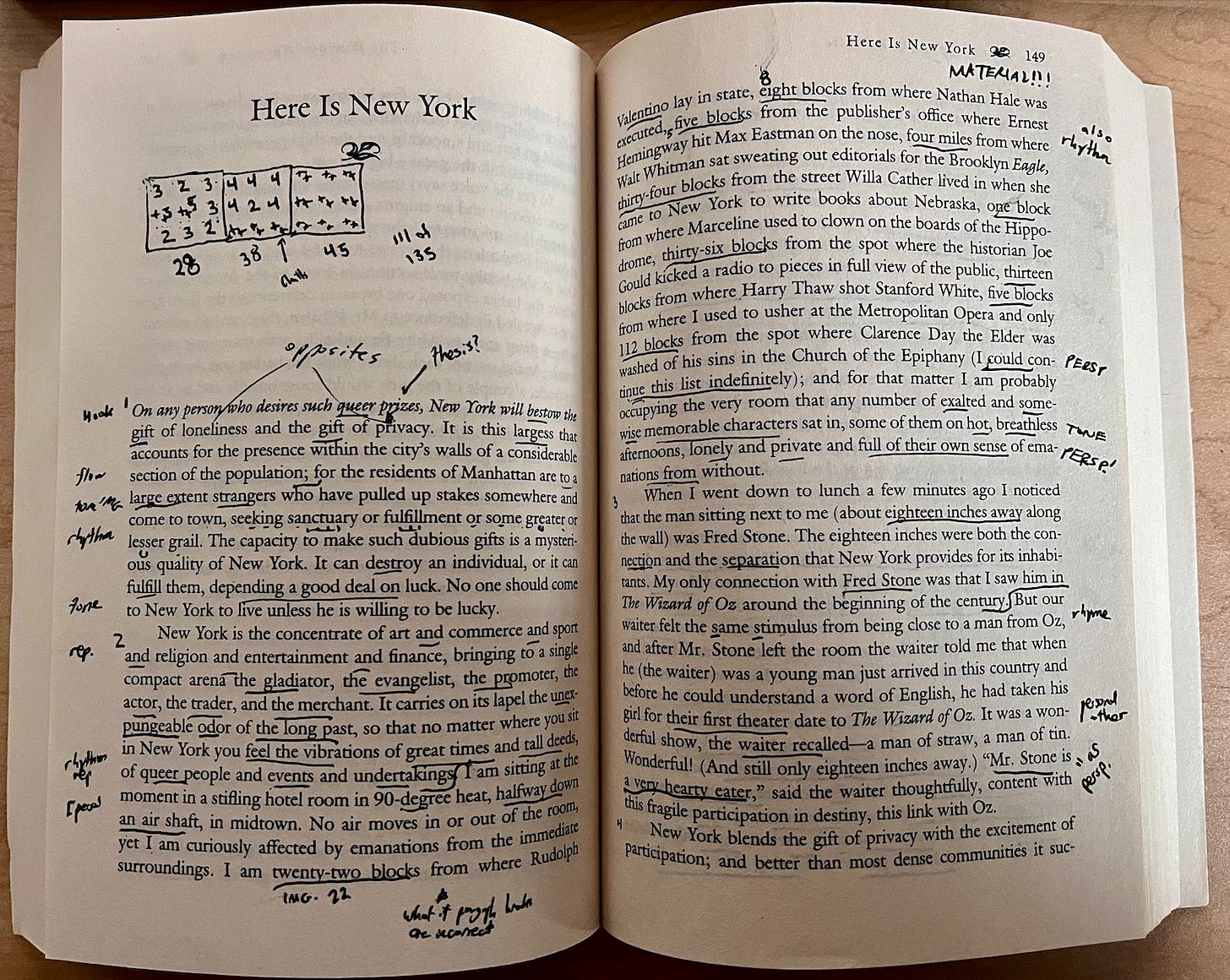

The only way to know is through benchmarking: if I manually scored 200 essays out of 135 points and then tested AI against my control set, I could see precisely how wrong it is. My manual score set is the north star for my AI development.

I’ll keep iterating through different methods—prompts, transformations, fine-tuning, syntax stats, etc.—to close the gap between my scores and machine scores.

This means I’m going to be reading a lot of essays, and that leads to the next announcement:

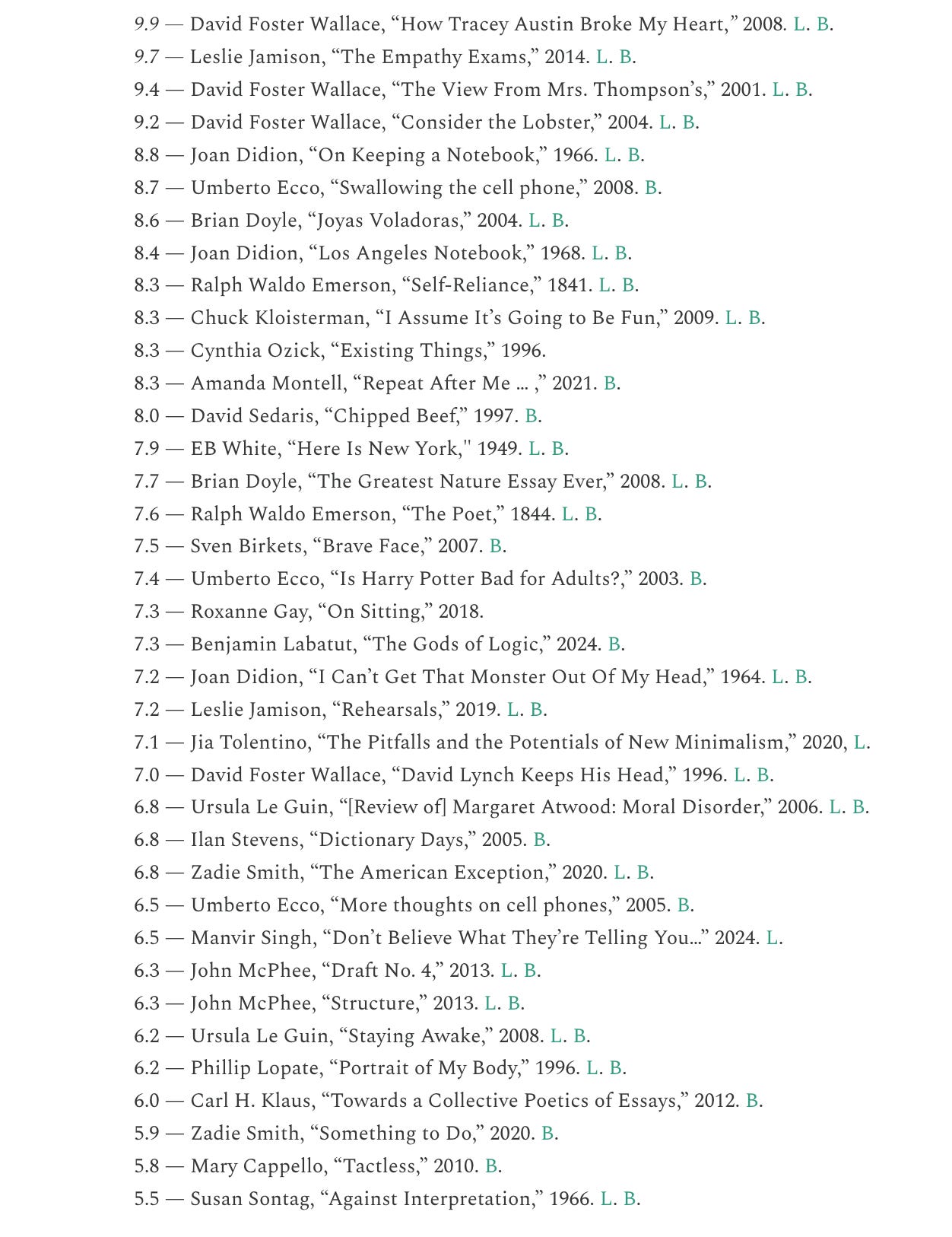

My list of scored essays is public_

This year I’ve been making monthly trips to The Strand Bookstore to build my collection of essay books. I try to read and score one every day. Each one gets graded out of 135 points. It’s manual, but enjoyable, and it also powers the whole project. My reading habit will lead me to a dataset of 5,400 points that I’ll use to interrogate a LLM.

It’ll take some time to get the AI scoring accurately, but in the meantime I’ll be sharing the essays I read here.

Currently the list has 37 essays with links to the URL. In some cases, it includes a link to buy the essay book on Amazon. Expect this to keep growing every week. For now, everything is manually scored, but once my AI is reliable, this can rapidly grow to include thousands—heck, millions?—of essays.

As you’ll notice, everything is scored out of 10; this score is a proxy for “formal completeness.”

It doesn’t matter how much I like the subject matter.

It doesn’t matter how famous the author is.

This system is blind to history, culture, and politics. It measures how well the essay scores on the Essay Architecture framework. Each pattern has equal weight. So many of the essays I’ve read excel in one dimension, but neglect others. It’s easy for a reader to get excited over a flash of brilliance, but as writers we want to know the consequence of each weakness.

This list is more a measure of well-roundedness than mono-dimensional power.

I sense that school has programmed our culture to get queasy around grades, and also to see anything south of 9 as some type of failure. In this system, anything above a 5.5 (3 out of 5) is a win and makes the list. Anything above 7.8 (4 out of 5) is great.

I know these scores alone don’t reveal much (why is Self-Reliance an 8.4?), so that’s why twice a month I’ll release detailed essay Reviews. You’ll see the score report, along with insights on how it’s working in each dimension. For the first one, I’ll be reviewing Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation.”

Based on the title, I went in thinking she’d oppose my whole project, but it turns out we’re on the same page:

“What kind of criticism, of commentary on the arts, is desirable today? … What is needed, first, is more attention to form in art. If excessive stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more … thorough descriptions of form would silence. … What is needed is a vocabulary—a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary—for forms.” —Susan Sontag, 1964.

Scoring systems usually have an agenda of harvesting attention through acerbic teardowns. That’s not the point here. The purpose of this list is to, 1) give you a reading list of inspiring essays, 2) teach you writing patterns through in-depth reviews, and 3) ground my analysis tool.

For the last year and a half, this newsletter has been called “Dean’s List,” but I think this name is better suited for my mega-list of scored essays. So, here’s the last update for today:

This newsletter is now called Essay Architecture_

Given my focus is to release a textbook and a tool, I figured I’d align my Substack’s name with that mission. That said, I still see Substack as the home for all of my creative projects.

I’ve set up sections so you can customize what you get in your inbox (sections: Essays, Chapters, Reviews, Experiments, Updates). At any time, you can update this in your account settings.

Here’s a reminder of what subscribers get each month.

All subscribers get:

A monthly essay, covering an eclectic range of topics, like the influence of American Idol on social media architecture, the role of psychedelics in ancient Greek religions, the nature of Beatles fan-fiction post-singularity, a biography of an online writer from 1994, and thoughts on Leap Year.

2 essay reviews per month, curated from Dean’s List, where I score and break down essays across history.

Previews of my textbook Essay Architecture. Once a month you get a full chapter that overviews 3 patterns (like this). While pattern posts are for paid subscribers, you’ll still get a helpful preview of each one.

A monthly update, aggregating links of my latest posts.

Paid subscribers will get:

All chapters of Essay Architecture—sent weekly—including visuals, examples, and prompts. Check out the 3 chapters within Thesis: Microcosm, Response, Catalyst.

A look behind the scenes, including typewriter drafts and the full archive of daily logs.

As I develop my AI editor, I’ll share beta releases with paid subscribers.

Founding members get access to The Writing Studio, a community of writers that meet twice a week to exchange drafts for feedback.

Here are some essays I’ve posted since last update:

And also, I went through and tagged all of my old posts. Now you have a tag cloud to visualize the multiple rabbit holes that exist on my site. Enjoy!

FEATURED : #2024, #alchemy, #altered states, #analog, #antiquity, #architecture, #artificial intelligence, #artist in the machine, #auto-bio, #auto-fiction, #cartography, #community, #consciousness, #covers, #culture, #decentralization, #deconstructed, #delirious, #editing, #essay architecture, #futurism, #internet history, #language, #lessons from artists, #logging, #logloglog, #mastery, # music, #nature, #new york, #religion, #social media reform, #synthesis, #techno-selectivism, #time, #transitions, #virtual reality, #warped incentives, #writing online.

Let’s riff:

What’s a favorite essay of yours you’d like to see reviewed on Dean’s List?

What’s a key feature you’re looking for in an AI-powered craft companion?

What’s a pattern you’re starting to notice across everything you read?

Footnotes:

“ur” is a German word for “old, original, elemental, archetypal,” and is independent from the Sumerian city of Ur, which happens to be old, original, elemental, and archetypal. The parallel seems to be a coincidence.

From Poetry as Insurgent Art (2007), by Lawrence Ferlinghetti:

“If you would be a poet, experiment with all manner of poetics, erotic broken grammars, ecstatic religions, heathen outpourings speaking in tongues, bombast public speech, automatic scribblings, surrealist sensings, streams of consciousness, found sounds, rants and raves—to create your own limbic, your own underlying voice, your ur voice.”

Ur’s thumbprint can be seen in ancient Greece and Rome, and yet we didn’t know its full importance until excavations in the 1920s.

I learned that it’s not spelled “mother load,” but “mother lode”: an underground vein of gold.

My three elements of voice (sight, sound, spirit) are weirdly parallel to this quote from Susan Sontag: “We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.” Joseph Conrad, independently, has a quote with the same three points: “My task is to make you hear, to make you feel, and, above all, to make you see. That is all, and it is everything.”

These aren’t prescriptive rules, formulas, or templates; they’re flexible components that writers can shape however they please.

Boondoggle is a new favorite word of mind. Here’s the formal definition: “work or activity that is wasteful or pointless but gives the appearance of having value.” But so you know, a "doggle" is a pair of sunglasses that stop dogs from staring at the sun, so a boon-doggle is something like “blinding hype” that is occasionally dogshit.

In software engineering, rubberducking is a type of debugging. By explaining your problem out loud—even to an inanimate object, like a rubber duck on your desk—the solution can pop into your head.

So excited for you! One immediate thought we can riff about longer. It seems like the general answer regardless of codification (the Ur as you mention) is that a great essay is subjective and objective. Which I think applies to big concepts like beauty and taste. We don't have the Aristotle of essays, but we do have what Aristotle has written about beauty, for instance.

Something worth thinking about.

“I’d rather alchemize minds than automate words.” Hell yea! I can attest to your profound questions in draft 1 to elevate draft 2. Very cool to see this all in writing. :)