I’ll confess: I’ve never read a memoir, I only experience them vicariously through

’s podcast where she passionately (and sometimes angrily) dissects them every other week. While great memoirs are a beacon for the potential of soul-filled writing, the bad ones apparently smother you with cliches, and an untrained reader won’t know the difference.In my recent DFW phase (anyone in a David Foster Wallace phase calls him DFW), I came across his 1992 essay, How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart. It’s a microcosmic masterpiece. He dissects Austin’s “Beyond Center Court,” and through this one memoir he sheds light on why the whole genre is a disappointment. Not only that, the essay is absolutely loaded with showing (not telling)–another Charlie-ism. I have her voice in my head saying, “don’t tell us your thoughts, feelings, or emotions, just show us.”

I immediately thought of her, but decided not to send it. The first time I mentioned DFW in casual conversation with Charlie, she followed up with a link-loaded email, and geez, I was oblivious to the Lynchian extremes he went to in his relationship harassment. But weeks later, her husband read that same Tracy Austin essay and insisted she read it. Now Charlie connects with David exclusively over their shared loathing of celebrity memoirs (visual of furious underlining, throwing books, and venting).

After some back and forth, we decided to do a collaborative review of a review.

First, check out Charlie’s latest post and her podcast where she breaks down why this essay shines as an example of showing (for example, the first page features 8 back-to-back quotes with no explanations).

I recommend following Charlie on Substack to see weekly examples of highly personal writing (like this, this, or this), and also on Spotify to get breakdowns like this episode in your inbox every other week. Each new follower is a vote for her to read and write a (scathing?) review of the Britney Spears memoir (please help make this happen).

I started my analysis by identifying and classifying each example; after impulsively counting them, it came out to a suspiciously perfect number: 100. There were 67 examples referencing Beyond Center Count, 41 of which were direct quotes. There were 30 other references unrelated to Tracy Austin (including other sports, Kant, the definition of “inspire,” etc.). Finally, there were 3 personal stories from DFW’s personal life mixed in: we see in a bookstore embarrassingly buying this memoir, we see him as an envious 18-year-old watching Austin on TV, and we see his self-consciousness intrude on his own tennis matches.

Assuming this essay is 5,000 words, that’s a density of 2 examples per every 100 words.

But aside from the sheer volume of showing, the main lesson for me (which I break down in my video) is how he has an insane “example rhythm.” Not all examples are equal; it could be a word, a phrase, a sentence, or a multi-paragraph story. Similar to how writers avoid back-to-back sentences of the same length to make their writing rhythmic, DFW is constantly weaving between small, medium, and large examples.

As exemplary as this essay is for the art of showing, I was shocked to learn that 45% of the essay still consists of the forbidden telling. Honestly, I think telling gets a bad rep. Yes, showing is the visual half of writing that immerses your reader in a hallucinatory trance, but telling has its purposes too. It frames what you show, and it helps transition from scene to scene.

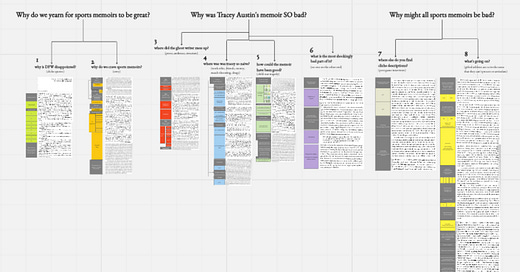

I created an outline that strips this DFW essay of all it’s showing so that you can see its skeleton (I’ve been finding it helpful to frame outlines as Q&A pairs). The bolded text below (his answers) are what he’s telling us, and each point is backed up with 10+ examples. The showing is the proof to support what he’s telling us. Telling without showing leads to flimsy and boring arguments. But telling someone a specific sequence of things with lucid visual proof is something like a psychedelic (def: mind-changing) experience.

Outline:

Why do we yearn for sports memoirs to be great?

Why was DFW disappointed? (it’s filled with cliches)

Why do we crave sports memoirs? (we envy quantifiable and televisable genius)

Why was Tracy Austin’s memoir so bad?

Where did the ghost writer mess up? (the prose, the audience, the structure)

Why was Tracy so naive? (child stars are ignorant to realities around excellence)

How could the memoir have been good? (it was a classic Greek tragedy)

What is so shockingly bad about it? (despite her crazy story, the words were pulseless)

Why might all sports memoirs be bad?

Where else do you find cliche language in sports? (post-game interviews)

What might be going on?(his thesis: gifted athletes are so in-the-zone that they can't process or articulate what’s happening to them)

Here’s a video called Structural Telling, Rhythmic Showing. It breaks down how he builds his structure around telling, but then ultimately grips and convinces us through different types of showing.

Expect more Deconstructions coming soon! If you like this or have any feedback, please let me know. I imagine some of these will be free and some will be for paid subscribers as they relate to my Essay Architecture project.

I’m still baffled at how the thesis of “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart” isn’t revealed until the last 20% of the essay! He does this a lot: in his essay about 9/11, the first 70% is about the plastic flags around town on the day after; he doesn’t even show the televised towers until the end. My next video will break this down (the “Elephant in the Room principle”). Consider subscribing so you get that when it comes out.

Let’s riff:

What are your favorite or least favorite parts about reading David Foster Wallace?

Anything to add on showing vs. telling? What works for you?

After my first draft of this, I saw the new Pope Francis memoir in an airport bookstore. A Google search told me that “Pope Francis is out to prove he’s just a regular guy” and it’s even narrated by Stephen Colbert. This feels like a solid choice to break my memoir virginity?

Love this two-fer!

I will make the time to properly digest this, but...

1) A collaboration with Charlie is always super exciting and I can wait to dive deeper.

2) I will never stop telling you how gifted I think you are and how grateful I am that you share your gifts with the world.