The First Online Writer

Lessons from Justin Hall on rendering your unfiltered consciousness into hypertext

Social media is so absorbed by the last 24-hours that we often forget there is a history of writing online.

Imagine being one of the first 1,000 people to launch a personal website in 1994. Put yourself in the shoes of a college freshman who suddenly has 24/7 Internet access piped into your dorm room. Most of the other sites are static: “hello world!” experiments, boring resumes, academic research…

So few people are online that you’re basically pseudonymous, and since you’re tech-savvy, creatively restless, and incredibly horny, you sublimate your entire psyche into an insane HTML maze, including your complete browsing history, porn links, a real-time memoir, an autobiography, a family tree, a psychological analysis of each of your friends, and basically every thought you’ve ever had.

No filter. You unleash the pinnacle of self-expression through the new medium of hyperlinks.

It’s a mix of link curation and storytelling. No one’s seen anything like it, and so naturally your homepage becomes the portal to the early Internet. You have so much traffic you crash the servers at your college. By 1995, your website hits 27,000 daily views, 4x the traffic of Yahoo!,1 and 1% of all Internet traffic (for context, that’s the same relative size of Mr. Beast, who now gets 360 million views a day).

Can you imagine your most vulnerable thoughts being so public?

This is the story of Justin Hall, the first online writer, and the first Internet-native celebrity. He revealed the potential of a new medium. He bared his soul in hypertext. He inspired thousands of people to write online. And in the end, the world crucified him for it.

30 years later, Justin is a father of two with a mostly private life, and the Internet is a radically different place. Billions are online. We’re all connected through feeds and social graphs, meaning any thought we share can be scrutinized by everyone we know; we censor ourselves. Most people don’t feel safe being real online anymore, including Justin.

I’ve been on a quest to make sense of Justin’s past by surfing through his HTML maze on links.net, which has over 4,794 pages. I’ve read every journal entry of his from 1996. I see him as the forgotten hero of online writers. Since I found his site in 2021, he inspired me to upload unpolished personal logs to my website everyday.

If you write online, you need to know the story of Justin Hall. It’s filled with inspirations and warnings about unfiltered self-expression. It might even encourage you to push the boundaries of what you're willing to share.

In celebration of Justin’s site, this biography includes 128 hyperlinks that drop you into different points of his maze. I recommend reading all the way through before you go tab diving (I’ve gotten lost for hours). Today, we’ll explore 4 questions as we unpack his story:

What was the original vision of the Internet?

What does digital self-expression look like in its most extreme form?

What are the benefits and dangers of oversharing?

How can we take creative risks in 2023 when the world is watching?

1. Healing through hyperlinks

When we thought blue underlined text could save the world.

We take hyperlinks for granted. But an early breed of confessional writers thought they would usher us into a digital utopia. Blue text linked the stories that anyone could now freely upload. They let strangers surf the inner lives of other strangers, triggering the timeless epiphany of “we are all one.” The first person to really embody this vision was Justin Hall. His compulsion to express every detail of his life online likely came from 3 things: the suicide of his father, his childhood obsession with computers, and the barriers to get online in the 1980s.

1984. At 8 years old, one year after his family got an Apple-II Plus in their home, Justin’s father, Wesley Hall, took his own life. Much of his writing wrestles with this event, and he has the obituary, eulogy, and suicide note on his website.

For a decade, Justin spent 2-3 days a week at a psychologist's office, making it normal for him to reflect and write about heavy emotions. As he aged, he became an investigator of his dad’s life. He looked through old letters to make sense of the past (like this note he wrote to his neighbors, criticizing them for the way they treated their dog). Perhaps these letters showed Justin the power of writing: a form of self-expression that could preserve one’s life and personality, through time and beyond death.

"Looking through old mail reminds me I want to be as great as my father[—] reading through his formal and informal correspondence, on legal blue carbon sheets … office relics of a dead man[:] either responding to city official ineptitude or encouraging … friends[, “] there's something so wonderful about that record[.”] I hope someone goes through my mail someday [and] tries to understand who I was.” Source.

The Internet would eventually fuse his desire for expression with his aptitude for computers,2 but there was a problem: the “world wide web” was off limits to Justin. In the early days, you needed credentials from the government, a research institution, or a university.3 He still managed to sneak online. Some older friends lent him their access codes and he found his way into the underground USENET forums,4 where they had discussion groups around taboo things like trauma, anarchy, beastiality, and psilocybin. In 1991, he published an article about the Internet in his high school’s newspaper,5 awestruck by the lack of restrictions, but frustrated that the average young person couldn’t get online without “borrowing, hacking, or waiting.”

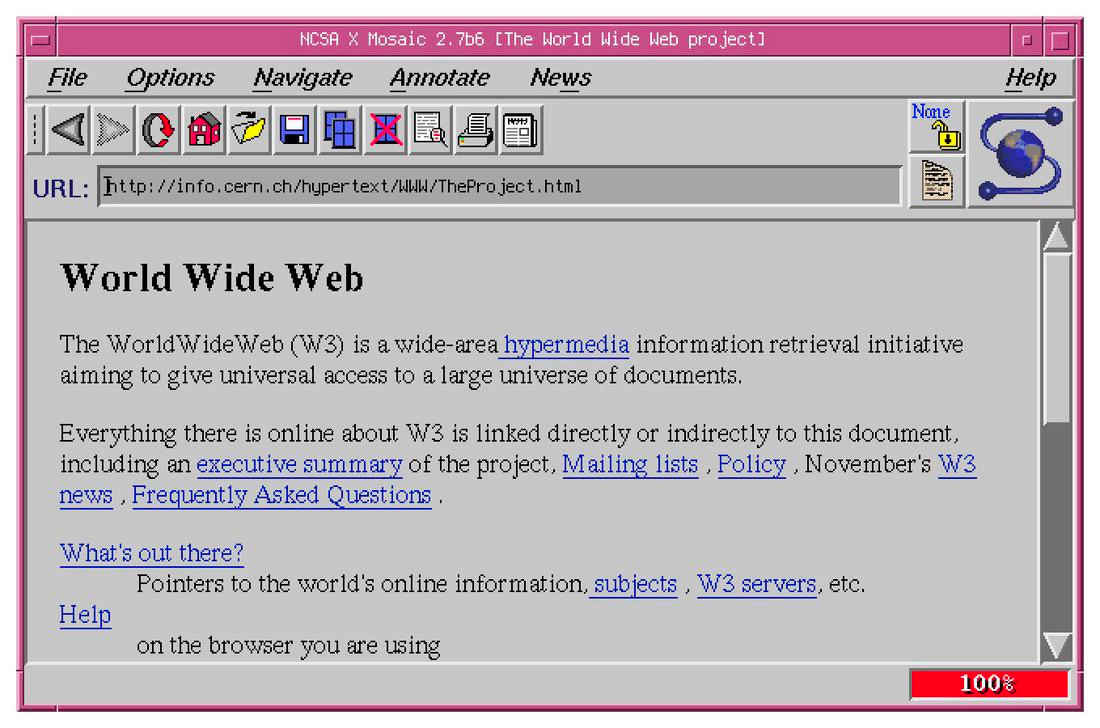

Justin started college at Swarthmore in 1993, which came with a digital river of dial-up Internet in his dorm room. That December he discovered “Mosaic” through an article in the New York Times written by John Markoff.6 The world’s first Internet browser arrived. It featured a simple interface, multimedia, the ability to upload HTML, and it worked on any operating system. But most importantly, it introduced Justin to the hyperlink, the invention that would shape his life:

“Before Mosaic, finding information on computer databases scattered around the world required knowing—and accurately typing—arcane addresses and commands like "telnet://192.100.81.100/." Mosaic lets computer users simply click a mouse on words.. to summon text, sound and images from many of the hundreds of databases on the Internet.”

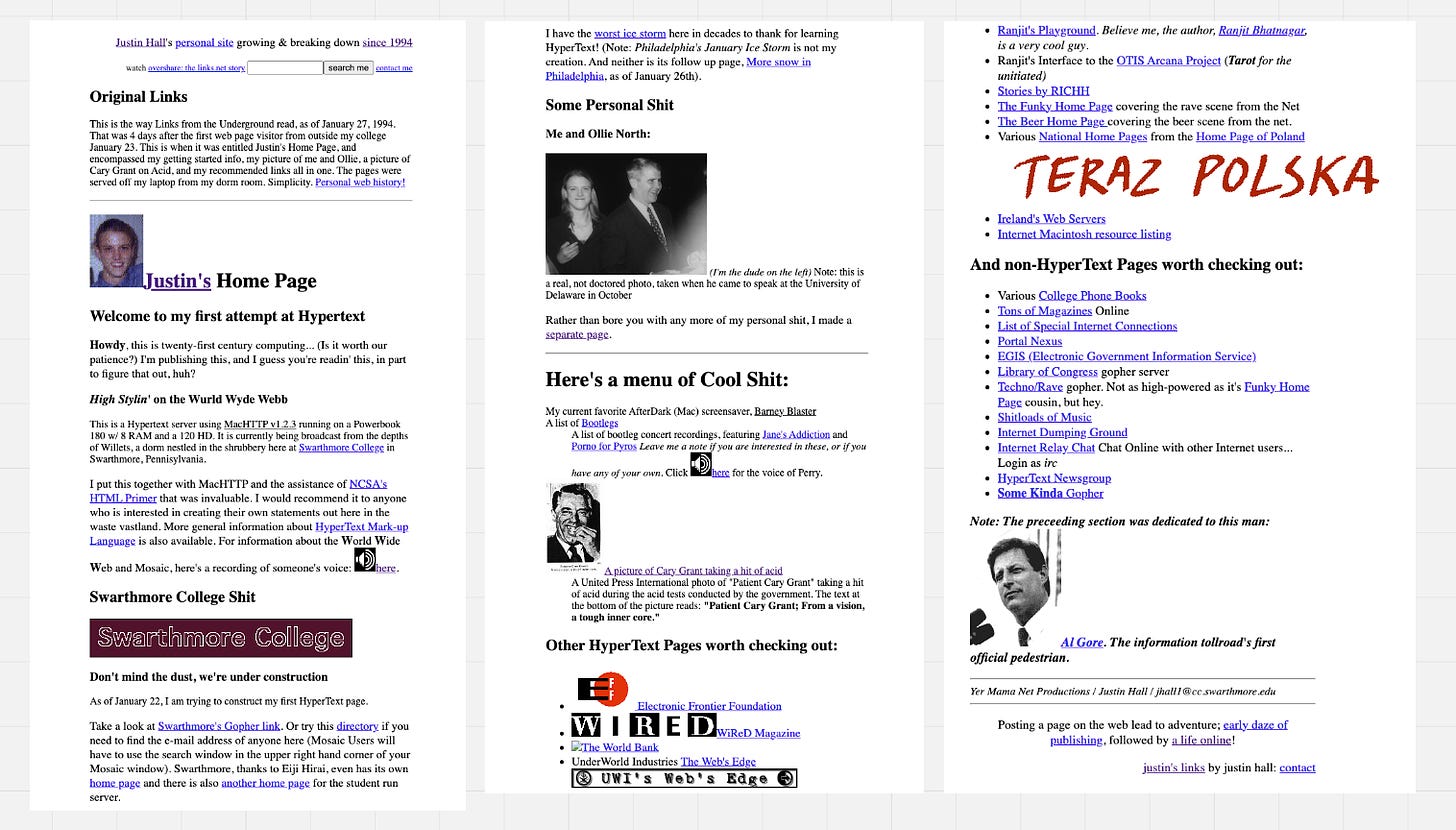

As soon as he got back to campus (January 1994), Justin built his first homepage, featuring prankster spelling7 (“High Stylin’ on the Wurld Wyde Webb”), tech specs, a photo of actor Carry Grant taking acid, a voice note of Marc Andreessen riffing on “global hypermedia,” and 52 links to websites he found interesting.

Some call him “the founding father of blogging.” While he didn’t make the very first website, he was the first to push the hyperlink to its limits. Justin raved to his friends about Mosaic, but had nowhere to point them; there was no search, and no list of trending sites coming out. So he took it upon himself to spend 8-10 hours a day surfing and indexing the entire early Internet as it emerged.8 It was small enough that you could catch up on the weekends. He got the domain name links.net,9 coined it as, “Justin’s Links from the Underground,”10 and became the master curator of the web.

By the summer of ‘94, Justin’s labyrinth was getting popular. He dropped out of school and moved to San Francisco after landing a job as an Editorial Assistant at HotWired.11 Justin was a 19-year old at the center of the digital revolution. The city was the throbbing heart of the self-publishing scene, with the highest density of online writers in the world.12 He moved into Cyborganic, a hacker commune of web experts located in the Mission District. Imagine a counter-cultural scene where everyone worked for HotWired by day, but at night they stayed up and smoked weed, pursuing their own personal Internet projects through AppleTalk ethernet hookups in each bedroom, all linked to a Unix server in the kitchen.

This group sensed that the Internet was a powder keg about to break into mainstream culture, and so the house was simmering with visions of the future. They envisioned a self-publishing revolution. Since anyone could express themselves online, they thought everyone would. In the best case scenario, the Internet would become an empathy engine. If everyone rendered their deepest thoughts into a hyperlink maze, it would break barriers and let strangers connect, fulfilling Tim Leary’s prophecy of “finding the others.”

The original vision of the Internet was utopian. While San Francisco of the 1960s was filled with LSD futurism, the ‘90s put their hope in technology. They replaced mind-expanding drugs with reach-expanding computer networks. A peer-to-peer revolution was brewing, and the Cyborganic house hoped to steer it. They wanted to spread the idea that your website is a symbol of your consciousness before the medium fell prey to consumer capitalism.

After one semester off, Justin went back to Swarthmore in the spring of ‘95. He returned with a missionary attitude, to push the limits of online self-expression, and to turn on the world to the healing power of hyperlinks.

2. The pinnacle of online self-expression

What could your website look like if you had zero inhibition?

Online writing today is often presented to young people as a form of entrepreneurship: focus on a single topic (no range), for a mass-market audience (no depth), and be careful with off-brand details (no glimpse into the logs of your life). Justin embodied the opposite ethos: write about a polymathic range of topics, at a depth that most people would never consider making public, and include detailed logs of your day-by-day experiences.

Justin returned to college as a sophomore with perhaps the biggest online audience in the world.13 While most of the tech visionaries of the 1990s were looking for venture opportunities, Justin was still only 20 years old. He was more interested in self-discovery, unfiltered expression, and cultural change. What emerged was fascinating. As I dive through his rabbit holes, I get the sense that someone’s consciousness was frozen into text. It’s a public digital memorial of a person at a specific time in their life.

Though Justin never broke down his own site along these three dimensions (range, depth, logs), they seem to me to be the pillars of Justin’s publishing philosophy. When an online writer does all three, they evolve from a flat caricature into a 3-dimensional portrait.

RANGE:

Justin wrote an essay called “scholarly schizophrenia,” a term to describe the delirious range of content on his website. The opening sentence is “I have problems with categories.” In today’s landscape, writers are incentivized to lean into a single topic and a single identity (you’re more likely to be remembered among the mass of Internet lurkers if you double-down on a brand).

But when it comes to self-expression, Justin gives the opposite advice in a post called webergy:

”Write about yourself,

your hobbies, your passions, your politics, your community,

whatever turns you on.”

Surf through links.net and you’ll notice the conceptual anarchy. You might find a guide to the band Jane’s Addiction, a long unedited paper on St. Francis from high school, his DJ set lists, notes on shamanism, his 1995 articles in the Phoenix newspaper, a short biography on Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, his ideas on dancefloor politics, a proposal for his college’s computer infrastructure, his dream journal, media theories on hypertext, a story about his appendix bursting at SIGGRAPH ‘95, or sex poems from his ex-girlfriend along with her monopoly strategy.

Similar to the nicheless of today, Justin struggled to define himself. He is an expanding constellation of ideas that can’t be compressed into a label. Instead of trying to find clarity within himself, he embraced the complexity:

“Schuldenfrei [, my philosophy professor,] accused me of being a hippy on the wires. I'm not just a hippy, I'm a punk. I'm a geek. I like jazz, and Jane's Addiction. I write poetry, sew, talk astrology, and spend eight hours a day on a computer. and I wear a suit and tie to teach.”

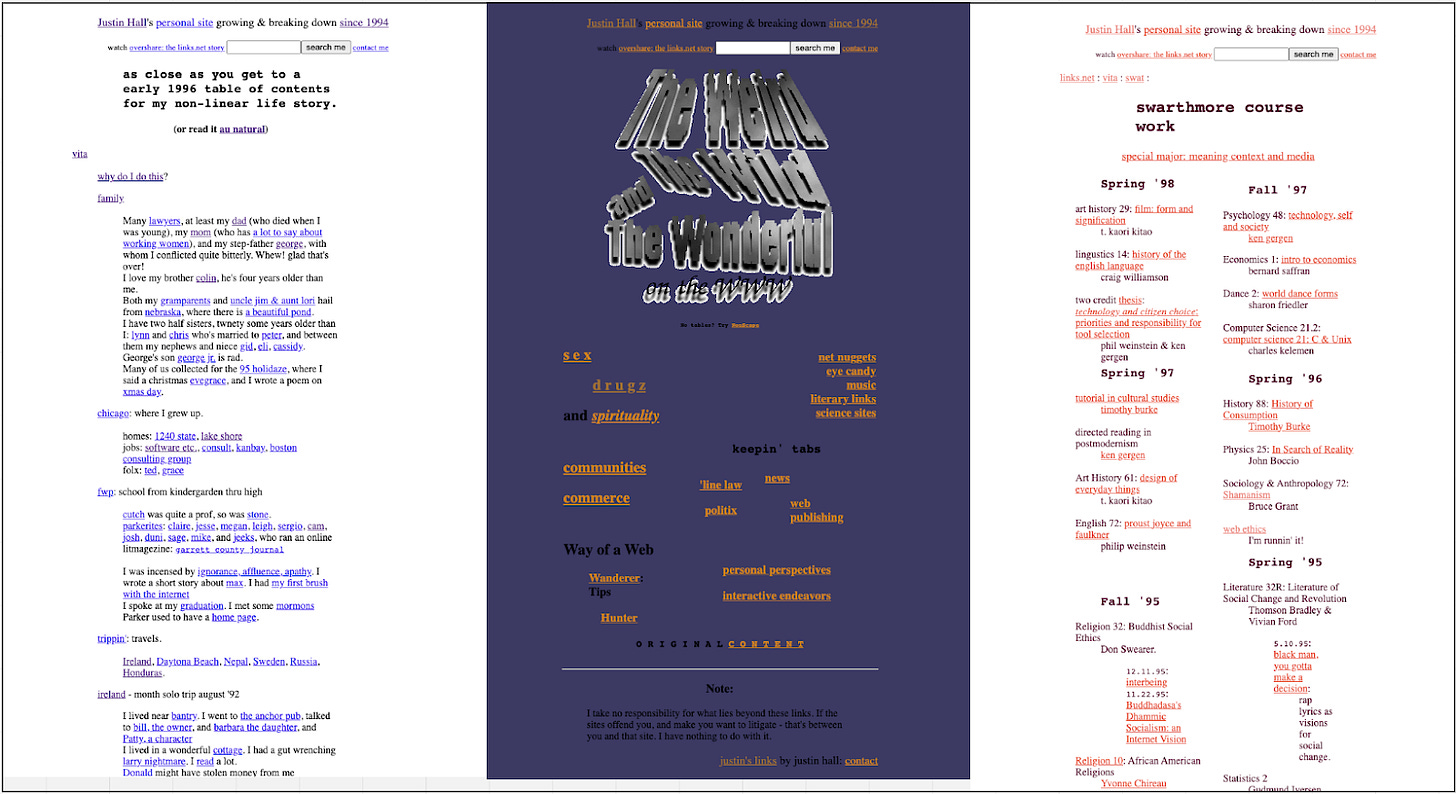

Instead of reducing his essence down to a meme, he took the “Choose Your Adventure,” approach. He made maps to organize his complexity and orient his readers. His Mindex from 96 is a cartography of himself, and his link portal (called “the Weird, the Wild, and the Wonderful on the WWW”) is a cartography of his browsing history. Some maps are sorted by media type, and others are organized by format (essays, short stories, poems, and coursework).

The downside of range is overwhelm. A new visitor won’t immediately get what you’re about, and they have to constantly make decisions on where to navigate.14 But the upside is extreme resonance. By rendering every part of yourself into HTML, and connecting everything through maps and hyperlinks, you let the reader venture towards the parts of your mind that intersects with theirs.

DEPTH:

The HTML writers of the mid-90s were known as “the online diarists,” and sometimes, “the escribitionists.” It’s a fusion of the word exhibitionist and scribe, so basically, “a nudist of the written word.” Justin wasn’t shy to expose himself in either the literary or physical sense. His website is an example of what your digital footprint might look like if you had no inhibition.

At one end of his vulnerability, he’s endearing. He invites you, a total stranger, into the intricacies of his family history. Justin has a hypertext autobiography he refers to as, “the textbook of my life.” The details that are typically saved for inner circles are just one click away: his early years in Chicago, the memories in his childhood home, a grade-by-grade recap of his K-12 schooling at Francis Parker, his gratitude for his mom, and his grandpa’s thoughts on death.

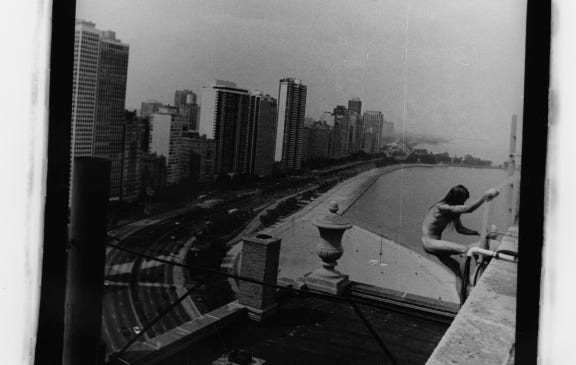

At the other end of vulnerability is the taboo: the things the average person would be embarrassed to publicize. You’ll find sexual encounters in his journals, write-ups on his STDs, a “nekkid” photo shoot (NSFW), a story on getting wrongfully arrested at a protest, scattered reports from 38 LSD trips, and the curiosity to see if drinking piss could heighten psilocybin trips. His willingness to experiment is equally as impressive as his willingness to share it.

At the core of this “hold nothing back” philosophy was the belief that people connect over repressed isolation. Justin got tons of emails from readers dealing with similar scars, like suicide in the family or alcoholism. Through reading the confessions of others, you learn you’re not the only one. The early web was underground enough that you could spill all your beans and strangers would reach out to say, “me too!”. From his post, links like life, he says:

“I'll talk to anyone who'll listen.

Joy and pain is pretty universal;

maybe you'll find catharsis or a sense of yourself within.”

Between 1995-1998, people around the world began the process of uploading their unfiltered life and history onto the Internet.15 In 2000, something called the “Online Diary History Project '' contacted and archived a few of the most prominent confessional writers. 15% of them cite Justin Hall as their inspiration. Here’s a quote from writer Carolyn Burke on the importance of sharing your depths:

"An online diary, a place that exposed private mental spaces to everyone's scrutiny, seemed like a social obligation to me. I felt at the time that I could give back to society something important: a snapshot of what a person is like on the inside. This is something that we don't get access to in face to face, social society. Our intimacies are hidden, and speaking of them in public is taboo. I questioned the privacy taboo. I disagreed with it. I exposed my private and intimate world to public awareness."

LOGS:

Starting on January 10, 1996, Justin uploaded a daily journal entry to the front page of his site.16

He seldom left his dorm without a camera, and never without a notepad. All day he would write his experiences by hand, and then upload them onto his website that night, sometimes as late as 4 am. On his 1996 homepage, you’d read about classes, parties, drugs, conversations, Batlhazar’s suicide rumors, VC meetings, threesomes. It was a feed of campus gossip, filtered from a single point of view.

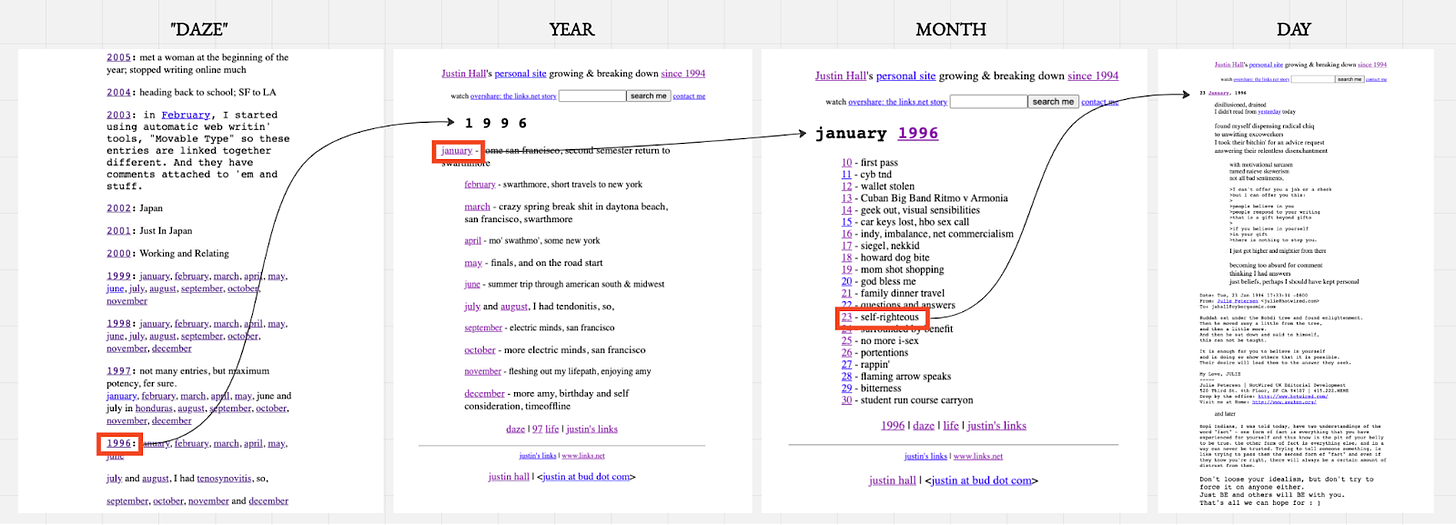

On the DAZE page (described by Justin as a “chronological miracle of navel gazing”), you can browse through the calendar of his life. You can click into years, and then months, to arrive at a particular day that he froze into text.17

I don’t think it’s accurate to call these “journals.” It’s not like he’s reflecting on a recurring set of questions to arrive at some heightened self-insight. He’s also not following a 3-page stream-of-consciousness.18 The word “diary” also feels less correct than the word “log;” it’s less like a deliberate introspection, and more like a blitz recalling of what happened to him every 30 minutes that day, typed out at full speed in chaotic open verse, leaving portals into his maze whenever relevant.

The excerpt below from January 26, 1996 is just one of 67 fragments on that day's entry. It’s semi-dense and takes work to decipher. But as you read through a chain of days, you build a fuzzy, almost impressionistic sense of what his day-to-day life is like:

“lingering in my room,

sharing personal web publishing potential

with a talented poetess; mary

who speaks as from a chink in the wall; quiet; honest

her response catches me off my guard; in my heart

"are you going to have kids?"

Less than a year after starting this practice, Justin refers to his own logs as “chronological puke,” calling it “amusing, probably indulgent, and definitely useless.”19 But decades later, I see Justin’s fractured prose as a cryptic wormhole into his consciousness. It’s half time travel, half brain transplant. I can occupy someone else’s head; what a rare privilege! Rarely do we get a raw glimpse into the “intrinsic perspective” of a real person (it usually comes from a fictional character). The Intrinsic Perspective is a Substack by

, and he defines consciousness as:“... what it’s like to be you. It is the set of experiences, emotions, sensations, and thoughts that occupy your day, at the center of which is always you, the experiencer...”

When you log frequently, you turn your consciousness into media. It lets you capture the little moments, the ones not notable enough to turn into an essay, but notable enough to replay in your head at the end of a day. By capturing your thoughts, they don’t fade to memory. By publishing them, you invite others into your reality.

Some of Justin’s peers were uneasy about his logging. They’d check his site every day to see if he wrote about them; everyone on campus was a character in his public drama.20 When people challenged his ethics, he’d tell them to write online about him. Justin wanted everyone to take responsibility for their own perspective through logging.

3. Oversharing

What are the consequences of holding nothing back?

Justin’s nature and pace of publishing brought surreal things into his life. The Internet is a serendipity engine; based on what you upload, it will match you with people, events, and opportunities of a similar kind. It’s an oddly specific matchmaker.

In the best case, it mysteriously unlocks the world for you. In the worst case, it’s a hell that explodes in unexpected ways. Justin got both.

1996, UNLOCKING THE WORLD:

Justin’s online reputation unlocked a range of things:

He landed internships and jobs at progressive technology companies like HotWired (‘94), Electric Minds (‘96), and Gamers.com (‘98).

It let him build a network adjacent to the “cultural elite,” the people on the front edge of shaping Internet discourse. He met John Perry Barlow in the same year he published “The Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (‘96). He had dinner with my favorite thinker, Terence McKennna (and got into a physical altercation with my favorite writer, Kurt Vonnegut).

Since he ran a high-traffic website, he had no problem getting speaking opportunities in mainstream outlets. He spoke on MSNBC, got featured in The Philadelphia inquirer, and delivered a talk called “Publishing Empowerment” to the RAND Corporation, a think-tank that pioneered some of the early inventions that made computing possible.

By the time Justin was a junior in college he was a cyber-celebrity.21 But separate from all the material opportunities, the coolest thing Justin unlocked was a cultural one: his audience enabled him to travel the country for free in the summer of 1996 to spread the word on self-publishing.

Justin taught HTML basics online and web ethics on campus, but he wanted to expand his reach. He felt a sense of responsibility to turn consumers into creators and to make sure the underprivileged learn to get online. He had the idea to tour the country through Greyhound buses and exchange websites for free lodging. If you let this Internet icon crash on your couch, he’d speak to your community, orient you to the digital underground, and build you a website so you have a megaphone to the world.

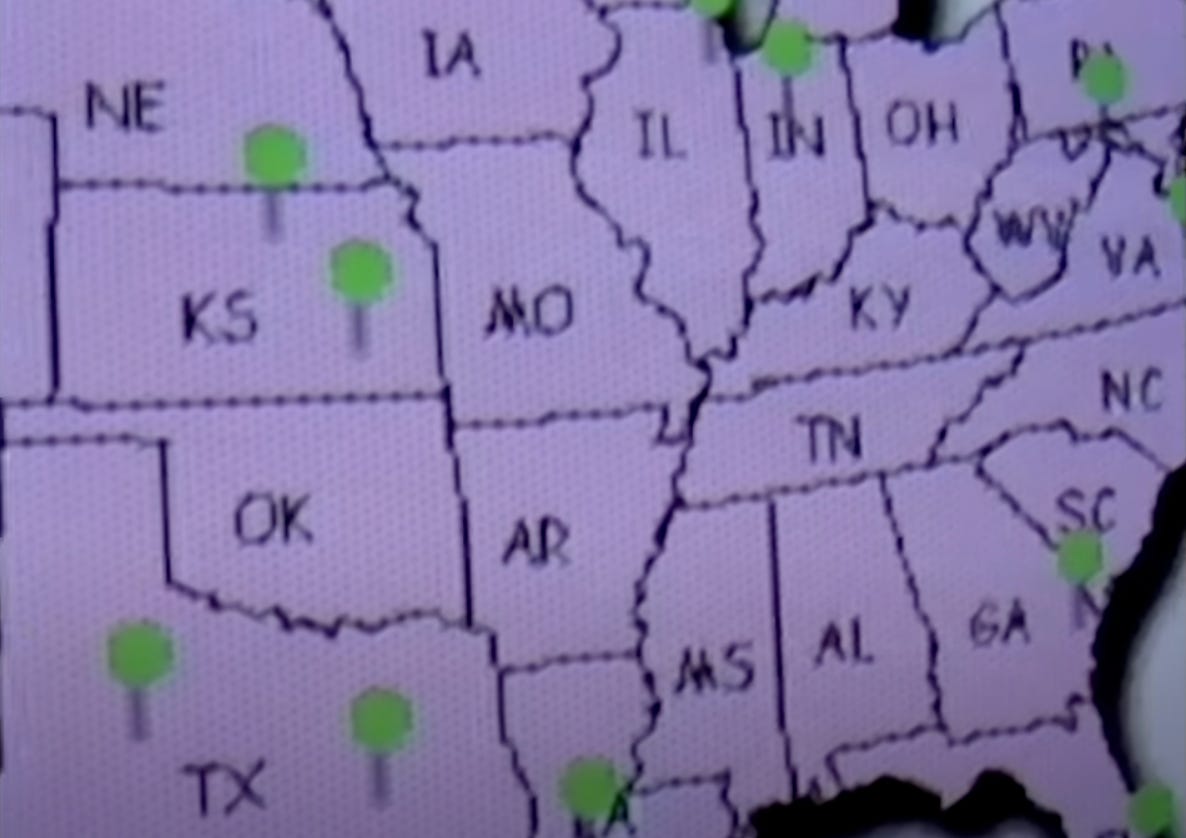

May 20, 1996. Justin set out and bussed through Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Kansas, Missouri, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona, landing back in San Francisco on July 3rd. He built websites for middle class Americans, and 10-year olds, and punks, and typewriter collectors, and the mentally ill.22 17 stops, 45 days, 100+ websites, barely sleeping 3 hours a night,23 he’d tape up his “why the web?” manifesto at colleges and coffee shops. He’s known as the “Johnny Appleseed of HTML.”24 The whole thing was filmed by Doug Block for a documentary called Home Page. Doug saw Justin’s voyage as “On the Road of the Internet Age,” based on Jack Kerouac’s novel from 1957.25 It was a great American road trip through the South, written by a young man on a spiritual mission, logging a portrait of his country as it was signing online.

It was a cultural odyssey, at a singular point in history, made possible through fearless self-expression. All that said, it didn’t bring commercial opportunities. Compare that to his contemporaries … In 1995, “Jerry and David’s Guide to the Web” got rebranded to Yahoo! (a backronym for “Yet Another Hierarchically Organized Oracle.”) Even though the co-founders were two months behind Justin in indexing the web, they were 6-8 years older, out of college, and hungry to start a business. In 1996, as Justin was preparing for his road trip, Yahoo! raised $33 million dollars from Sequoia. Meanwhile Justin was behind on his server fees, opposed to banner ads, and opted to raise $714 in donations from his audience.

Justin had the outlook of an artistic cyber-prophet, and ultimately thought that culture could beat capital. But in the end, the forces of Silicon Valley would scale and turn Justin’s own website against him.

SEARCH RUINED EVERYTHING:

As Justin continued to share his whole life, the web was evolving. The way to find information was shifting from browsing to searching.26

Maybe you remember the first time you typed your own name into a search engine to see the results (known as “ego surfing”). Imagine if the first link was a peculiar website called links.net, featuring Justin writing his full recollections of your time together, and a detailed analysis of your personality.

At first, Justin found humor in these conflicts. “I’m a writer, what do you expect?” He referenced Truman Capote’s “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” where the author profiles and exposes New York socialites, alienating him from his friends.

But as online circles grew, it became less safe to be weird. Unfiltered self-expression backfired.

The first real issue came up in 1996 with his ex-employer, the Boston Consulting Group. Justin worked an internship there in the summer before his freshman year. They didn’t have their own website, so when prospective clients searched them, the first thing they found was Justin’s expressive blog post about their all-expenses paid retreat in Wisconsin (from the perspective of an 18-year-old). He highlighted a night of drunken karaoke, where a senior exec gave a slideshow on mushrooms, and he slept with the 23-year old girl from accounting. Everyone’s full name was featured.

Justin ignored their calls, so they repeatedly harassed his mom and showed up at her house, until he agreed to omit some of the details.

Little by little, his friends would say, “dude, take my name off your website, I’m going to lose my job.” His family became more guarded at dinner, knowing anything they say might end up on his front page. The ethics of a “hypertext autobiography” began to break down. Justin realized that maybe it’s not his role to tell other people’s stories. His logs got more and more impersonal, until he eventually lost momentum with them.

Justin’s time in college (1993-1998) aligns with a massive transformation in the Internet. When Justin entered college, there were about a thousand people online, the web browser had just been invented, and it was a terrain of self-expression. When he graduated, over 100 million were online, venture-backed companies were competing for mass adoption, and Google search was released.

Out of school, Justin got offered a dream job: a weekly TV segment to teach viewers how to build websites. But after two episodes (9/22/98 and 9/29/98), the station got complaints from their conservative viewers. They found his site and complained: “Who is this homosexual freak pornographer?! If you keep him on air, we’re going to boycott your channel.” The network told him to take down some pages or resign. Justin walked.

The breaking point came when his own audience began dissecting, analyzing, and rooting against his relationships. Justin was falling in love, but his readers started citing episodes from past failed relationships in his comments. They formed theories around Justin’s personality; they weren’t wrong. His new girlfriend was freaked out, and he had to decide between his website and a real person.

At this point, self-publishing wasn’t serving him anymore; it pissed off his friends and family, it lost him jobs, and it threatened his future. He got hit with the dark consequences of oversharing, and decided to sign off in 2005. Self-expression turned to self-censorship. He’s made some brief appearances since, but the ethos of radical range, depth, and logging hasn’t returned since the ‘90s.

[<p>] In hindsight, the [“] “webheads [<em>] lost control [</em>] of the very medium they created” [”]. In the early days, [<strong>] you could only share online if you knew how to write HTML [</strong>] and handle your own hosting. Platforms changed this. [</p>]OpenJournal, LiveDiary, Movable Type, Blogger, and Xanga all came out in the late 1990s, making it easier to share, bringing more people online, and creating social pressure. People felt less comfortable being open. It began a period of standardization, and “the personal website” was replaced with templates and reverse chronological feeds.

Since then, we’ve been lodged in “the Impersonal Internet.” The global village scaled into a global metropolis. Now, anyone can publish, but almost no one does. A Neilson study in 2006 reported “participation inequality” across all online communities, where 99% lurk and only 1% of people actually post. It’s precisely the dystopia that Justin Hall and the Cyborganic crew in 1994 were trying to avoid.

4. Legacy beats self-censorship

Why and how to overshare in a world where everyone’s watching

Here’s a paragraph from Justin’s autobiography about the present:

“By 2022 I find myself the father of a second child, and learning more about fatherhood than I knew awaited me. I visit the public library to fetch books for my kids at least three times a week. I volunteer at their schools. So aside from my work building software to help adults find cannabis, I'm pretty focused on parenting at the moment. I feel grateful to have the opportunity to focus on it. I find it challenging and therapeutic.”

Justin seems to be in a new and fruitful chapter of life, and hyper-publishing doesn’t play a big role in it (he tweeted twice in 2023). What’s the lesson here? Maybe you feel the world is just so different now than it was in 1994, that the era of radical transparency is over. Maybe you think links.net is a fascinating relic of the vintage Internet, but the method isn’t a philosophy to live by today.

But I see links.net as a model for the kind of website I want to build. The fact that Justin’s consciousness from almost 30 years ago is frozen into the Internet is perhaps the most interesting part of this whole story. Decades later, here I am, reliving his past in detail. His adventure is perhaps fresher in my mind than his, considering I’m the one “going through his mail to understand who he was.”

In a strange way, his decades-old story is helping me steer mine today. He’s helped me push the limits of my own publishing, while making me aware of the consequences. Since I found his site, I’ve uploaded over 275,000 words of daily logs to my site and hope to keep up the habit for the rest of my life. There’s a range of reasons for why you should write online, but Justin reminds me that writing for the future is the most wholesome and sustainable purpose.

This quote from JD Salingers summarizes why you should make your inner life legible to the world:27

“Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You’ll learn from them—if you want to. Just as someday, if you have something to offer, someone will learn something from you.”

You might impact people long beyond your time; it could be your own kids, the kids of your kids, or a total stranger like me. This brings the story full circle. Justin spent much of his life making sense of his dad’s life, and maybe his whole extreme blogging experiment was a way to leave a trail for his descendents. In a 1998 Swedish documentary, he riffed on the potential of inter-generational writing:

“Imagine if all your relatives had web pages, all their relatives, even their dead relatives, telling stories from before you were born.”

I’ve never met one of my grandfathers, but I learned that he wanted to be a writer. I recently found 3 chapters of an unfinished World War 2 novel. It was neat to read his prose and meet the characters of his imagination, but it didn’t give me a snapshot into his life. Through his bookshelf in my grandmother’s basement, I can approximate his range of interests, but I don’t know his inner depths. I have no logs of his days. My only impressions of him are from second-hand stories, and so the truth of his consciousness is a mystery to me.

Imagine if he wrote more? I could have a full grasp of his life, and I could understand his struggles in the context of mine.

So while there might be consequences to oversharing, it’s worth trying to make it work. It can unlock the world today, while also leaving something for the far future, whether the audience is millions of people or your 5 grandchildren (who might be your biggest fans). But having a long timeframe doesn’t mean we should share recklessly and ignore the present:

How can you explore without confusing your audience? How do you unpack intimate depths without compromising your loved ones? How do you share your logs when the whole world is watching?

How do you overshare without getting burned? Here are 3 ideas.

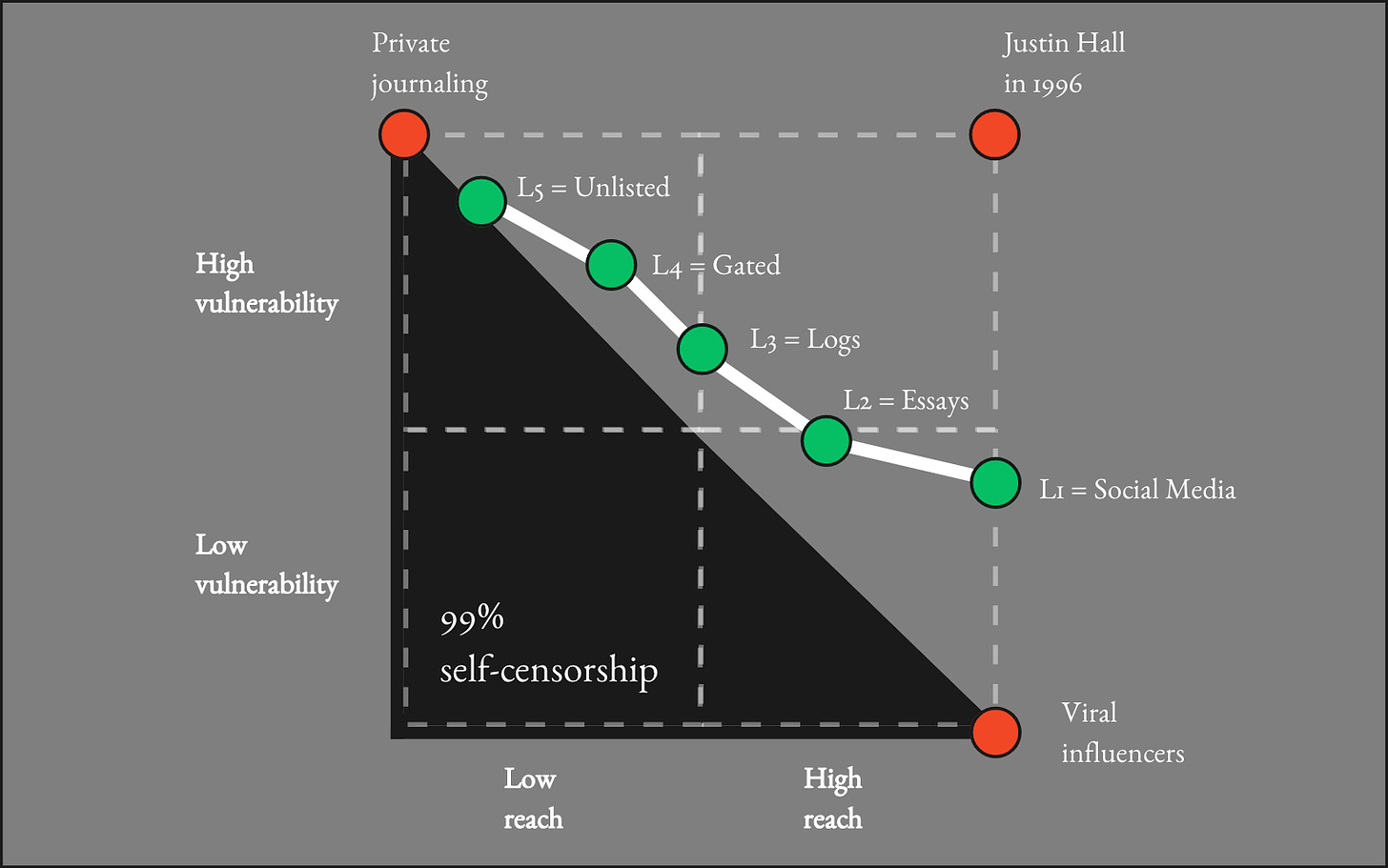

THE PRIVACY SPECTRUM: On a stage, you’re more likely to perform. At a campfire, you’re more likely to be real. This is natural, and applies to self-publishing too. Check out Low Stakes, Strong Takes by

. You don’t have to pick between vulnerability and accessibilty. You can have a range of writing that straddles the privacy spectrum. Most writers would benefit from having a middle ground, a public URL on their site where they can go off-brand, that’s only clicked into by the people who care to explore your mind (more here on the benefits of public logging).Consider how there are different “levels of accessibility;” you can make it so your most vulnerable work is only found by the readers on your team:

L1: Content designed to hack the Twitter algorithm and go viral (50x your audience)

L2: Newsletters delivered to the inbox of all of your subscribers (50% of your audience reads)

L3: A page on your site that’s there for true fans to explore (5% of your audience reads)

L4: Gated or paid content for committed fans who want to support you and dive deeper (2% of your audience)

L5: Unlisted URLs to share with specific friends (a handful of people)

PSEUDONYMS: When Justin started, so few people were online that almost everyone had the benefits of pseudonymity. But today, everyone in your life can search for you and read your thoughts. Chances are, you’re self-censoring without realizing. Where might you share a paragraph of how your day went? Do you feel the liberty to write about sex, drugs, and failure? If not, chances are you're carrying baggage under your name. I tried writing under my legal name for 6 months and my essays were stale and safe. As soon as I dropped my long Greek last name and elevated my middle name, writing became untethered and transformational. Michael Dean is a “half-pseudonym;” it feels like an honest identity, with an added layer of SEO defense (when you search Michael Dean, a shirtless MTV reality star pops up). The privacy made it easier to take creative risks online, and I’m gradually sharing my site with people in my life. If you’re considering a pen name, check out The Pseudonymous Cape by

.

PLATFORMS – The feed-based model of social media is designed to boost advertising revenue, not to enable people to connect and express themselves. We need new platforms with a core mission of enabling range, depth, and logs– not just reach. Substack embodies the ethos of independent publishing, and might be the only platform I can think of that enables L1-L5 sharing. It’s also worth checking out Plexus (

), a startup using AI to connect people. Instead of being greeted with an addictive feed, you start by sharing a thought, and then it constructs a feed of posts that are most related to it. You have the confidence to overshare, knowing that no one on the network will see a post of yours unless they reveal something of a similar nature. It eliminates the stage effect.

Hopefully, Justin’s story, paired with some practical ideas on how to “overshare” in 2023, have gotten you to question what you share, how to do it, and why it’s worth it.

There are multitudes within you. Your taboo secret depths are also present in millions of others. And the day-to-day mundanities of your life might feel sacred to someone else, either now or in the unimaginable future.

So go off-brand, at least on your personal website. Do whatever it takes to overshare, whether it’s about controlling visibility, adopting a pen name, or finding a better home to host your thoughts.

Unlock the world through self-publishing. Find that group of 10 people who become conspirators on your journey, and add nuggets to your time capsule as you go (let me know if you figure out century-long domain hosting).

Extend your time horizon to 10, 30, or 100 years into the future. Imagine someone outliving you and reading your blog, whether they’re a descendent or a stranger, thinking “wow, what a life,” adjusting their own accordingly. When you write with legacy in mind, there’s no reason not to push the boundaries of how you express yourself.

Special thanks to Justin Hall for the courage to go first.

Let’s riff:

What are your impressions of links.net?

What do you want to bring into your writing practice? (range, depth, logs)

How might you overshare without getting burned?

Feedback thanks:

- helped me with several rounds of detailed edits on this piece. He just published Promethean Barbie, a story showing how both Robert Oppenheimer and Ruth Handler connect to the myth of Prometheus; someone tries to do something good and gets misinterpreted and tortured for eternity. This archetype is so common among artists that find fame, and it kind of happened to Justin Hall too. He was all about increasing empathy through writing online, but with scale the Internet turned on him. Garrett shares thoughts on why you should create and invent, despite the risk of being misunderstood. Garrett is a great thinker, writer, and editor, and you should check out the site he’s building with Notion.

- gave feedback that helped me organize this essay around 4 questions, and brought out the angle of “so what does this mean for today?” She just published Learn The Rain Dance, an essay about learning to live with fear, instead of avoiding it or pretending you can overcome it. It’s so related to this essay; continuously pushing the boundaries of what you share in public comes with a regular dose of fear. It never goes away, even with experience, even under a pseudonym. This is a good thing; fear is a compass. I admire the depth in her writing, so check out her Substack for literary portraits of the human condition.

Make sure to check out Justin’s documentary Overshare to hear his story from his perspective (filmed in 2014, 41 minutes), and here are a few other links to dive into:

Home Page (1999): A 1 hour 41 minute documentary, filmed in ‘96..

10 Years of Links.net (2004): 10-year reflection..

XOXO Festival (2014): 20 minute talk..

Internet History Podcast (2017), 1 hour 45 minutes..

Walter Isaacson’s Youtube (2021): 15 minute video..

Footnotes:

Yahoo! was the biggest web portal of the mid-1990s. By 1998, it was getting 95 million page views a day. But in it’s first year (1994), it only had a million views total. Given that Internet users grew from 5 to 15 million that year, I estimate Yahoo! to have had 163,00 hits in December of 1994. This comes out to over 6,000 a day, just a quarter of what Justin Hall had at the same time.

Justin’s mother hired him a “computer tutor” when he was a teenager— basically, a guy to bring over pirated software and teach him how to code in Basic. The computer was his babysitter, and at 14 years old he worked in a software shop and played every game that came out on IBM between 1987-1990.

One of the main ways to get online from 1986-1992 was the NSFNet (The National Science Foundation Network). It replaced ARPANET as a way to link research facilities, and prohibited commerce. The NSF acronym is so close to NSFW (not safe for work), and the irony is that this explicitly work-focused network had an uncensored underground on it.

Think of USENET as a primitive Reddit of the 1980s. Imagine calling a remote server through a phone number— wait until you hear a tone, then place the phone itself onto the modem, so two phones can screech at each other, sending text through landlines. Text would slowly render on your screen. You could use the arrow keys to browse through hundreds of different community forums.

An excerpt from Justin’s 1991 article on USENET: “Any problem, any idea, any organization, anything is in these newsgroups. There are groups for Celtic, Arabic, and Nordic culture. There is a group for pagans, for bisexuals, musicians, animators, poets, narcs, Deadheads, ZappaHeads, computer geeks, speed freaks.”

If you’re looking to better understand the origins of computing (and the cultural landscape it grew from), I highly recommend John Markoff’s “What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry.”

The mutation of language was a symbol of the freedom from traditional publishing. When no one stands in the way of you sharing words, why not bend the words themselves? (my guess).

I love this description from Justin’s friend who watches in awe as he surfs: “With Justin at the mouse, we distributed our brains between the five or six Mosaic windows that were always open, clicking on new links while waiting for others to load and startled by an endless sequence of impossible juxtapositions. Justin urged us to follow a link labeled "torture" while an animated diver performed background somersaults and an anonymous Indonesian artist gave us a glimpse of demonic possession. The images went by so fast, and yet so disconnectedly, that time itself seemed to be jerking backwards, as if Mosaic were a sort of temporal strobe-light creating the illusion that the evening was flashing before our eyes in reverse. "This way beyond MTV," Josh said. "It's a whole new level.” September 9, 1994.

In 1994, Justin got links.net as part of The Great Domain Game (or, How to Squat on the Internet). He shared his story on how securing fuck.com in 1994 was a distinct possibility, and how he ended up getting bud.com which he turned into a cannabis delivery company 24 years later.

His link portal was named after Dostoyevsky’s “Notes from the Underground,” a book he admits to have never read.

HotWired was an online offspring of WIRED, a magazine founded the year before (‘93) as “the Rolling Stone of technology,” citing Marshall McLuhan as their patron saint. The website was led by Howard Rheingold, a seasoned tech-pioneer three decades older than Justin, who just released a book called “Virtual Communities” in 1993. Howard knew that hyperlinks enabled active participation, interactivity, and collaboration; he wanted something beyond an online zine. They were gearing up for a comment-focused proto-Twitter in ‘94, but Editor-in-Chief Louis Rosetto pushed back, saying (essentially), “this isn’t fucking amateur hour, it’s an expression of the WIRED brand.” He feared lo-fi HTML and spam comments— and instead pushed for paywalls, banner ads, and high-res images that might take 45 seconds to load. Within 6 months of launching, half the company left.

Here’s a IM message (from an app called Spacebar) Justin shared on October 28th, 1996, which alludes to Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (rooted in SF): “I have seen the best minds of my generation strung out on HTML starving hysterically naked for JavaScript standardization hating Microsoft disillusioned and cold and hungry combing the Haight Ashbury streets for an angry fix.”

Around this time, much of Justin’s traffic still came from the comment sections of his sex links. An anonymous user (the original troll) posted a link to something “a hot and steamy threesome (?),” but it actually pointed to the University of Indiana homepage. It crashed the college’s server. Justin didn't want to become a vehicle for “weaponized attention,” and started decommissioning comment sections around sex links— from: January 25, 1996; “I’d rather have a few users diggin’ on my words than thousands diggin’ their crotch. I’ve got better things to do with my bandwidth. Heck, I put up a solicitation. If they likes it that much, they’ll pay for me to get a bigger phone line. But I ain’t goin’ sacrifice teachin.” His readership quickly dropped from 27,000 to 11,000 daily readers.

No matter how you enter the maze, any given page is a hyperlink salad, filled with portals that can take you in 10 different directions.

Some writers seriously pushed the limits of public honesty. The most extreme case, featured in the documentary Home Page, covered a female blogger writing about a martial affair as it was unfolding. Once you develop a serious publishing habit and commit to rendering your life into online text, it almost feels as if something doesn’t exist unless it’s in HTML.

The genesis of this habit came from a party celebrating the three year anniversary of WIRED. By 1996, Justin’s site was a sprawling jungle with 3,000 pages, and his friends from suck.com teased him that they couldn’t find anything in his maze. They shared that the most popular sites on HotWired were homepages that updated everyday. People want a reason to check back, not a pamphlet. “At suck, you get sucked [in] immediately; no layers to content. They’re urging folks to make it their homepage (it changes daily).”

For another glimpse into a fully documented life, check out this 28-year archive of “The Gus.”

Julian Cameron’s “The Artist Way,” came out in 1992, the same year as the Mosaic browser. Many people who read that book learned HTML so they could share their Morning Pages online.

Even his mentor Howard Rheingold wrote off his web writings as a “compost heap,” saying he’d be embarrassed if the thoughts of his 23-year old self were published online. Contrary to this point, one of WIRED’s editors (Steve Silberman) said, “Now, it doesn’t even matter what the mainstream culture is doing, because you can cut right to people who are interested in what you’re interested in, and put yourself up there unedited— unedited data is a pearl beyond price.”

The girl’s bathroom stall at Swarthmore had engravings about him. It started with a question: “What does everyone think of Justin? Cult of personality? Megalomaniac? Genius? Entrepreneur? Weirdo?” One of the responses was, “Justin has never been breastfed. I’m not suggesting that’s the sole cause of his extroverted behavior, but to me I sense it as an underlying explanation for his search for attention.”

An angry reader referred to him as Jim Morrison of the Net.

At the Breakthrough Club in Wichita, Kansas, Justin spent hours helping 6 mentally ill folks—each typing with one finger at a time—to build their own website. He helped a 72 year old illiterate truck driving woman named Cleota build a website to tell her story. In an interview on MSNBC, he said, “these were the kind of pariah’d voices you might not see in the sanitized tech world.”

Justin was so charged through his mission that it strained his body. He was often cranking out posts from the back of a Greyhound post for hours with terrible posture. He developed a terrible tendinitis in his wrists and had to stop writing for 2 months.

It was a Tim Leary spirited mission: instead of “tune in, turn on, and drop out,” they pitched the slogan, “fry your mind and change the world.” Symbolically, Leary died during this road trip.

In a bizarre fusion of timelines, Justin and some friends rang the doorbell of William Burroughs (a literary legend in Kerouac’s novel) in the last year of his life. He invites them in, they chat about the Internet, and feed his fish together.

Prior to Google, search engines like Altavista, Lykos, and Infoseek were around in 1995, making the web more discoverable to the average person.

Wow--fascinating and powerful essay. I’ll be thinking about Justin Hall and your reflections on him for days. This is a provocative challenge: “Your taboo secret depths are also present in millions of others. And the day-to-day mundanities of your life might feel sacred to someone else, either now or in the unimaginable future.”

This makes me think about the necessary chaos at the margins of every system. Just before I read this essay, I read Henrik Karlson‘s essay about how blogs are search queries for people that are interesting. And then he mentioned how he tells his daughter that the Internet is like this alien life that we don’t know much about and we don’t know how it works, but we can wave our hands and click certain buttons, and cat videos show up or porn shows up.

And I think about how all systems need “marginal land” of wilderness in chaos, in order to keep the mainstay of the farm healthy.

And it makes me wonder where people like you and I fit in the mythical landscape of this Internet creature that we are trying to interact with. We’re trying to find an archetype, without having to think so hard about it. Justin, for example, knew where he stood and he knew it energies to draw on, in order to keep his place in the mythological landscape alive. And he knew when he was losing that because it was affecting his relationships in his normal life.

That’s what my mind was working on as I got to the section of your essay about how to balance privacy and reach. I’m less likely to graph it out and try to plot where I want to be, but I can use this is a short hand to figure out what energies this world is giving to me and how did lean more into those energies, especially if it’s where I want to go.

And yes, reading about Justin did make a dent on my psyche and make me wonder how I want to approach this whole world, so thank you for putting the story together