”People who make things for the Internet endure a psychological tug of war between the artist and the algorithm. Please only yourself, and you’ll miss out on the gale force spread of a viral post. Please only the algorithm, and your work will taste like soul-sucking milquetoast.” – David Perell

The tension is real. I’m naturally drawn to a delirious range of topics. In my essay queue are ideas about AGI, the origins of Christianity, the UI of text editors, American Idol, Curious George, and a story about how my grandfather ate my dad’s pet rabbit in the 60s. None of these ideas are practical, nor is there a clear theme uniting them. But separate from this boyish urge to explore is another temptation, an urge to wrap myself in plastic, feed the algorithm, and shoot myself into the veins of the Internet as a legible, likable plastic guru, a caricature that can devour the world and myself.

Be the true artist and toil? Or be the marketer and sell out?

It’s not a choice. Do both. That’s what Alphonse Mucha did.

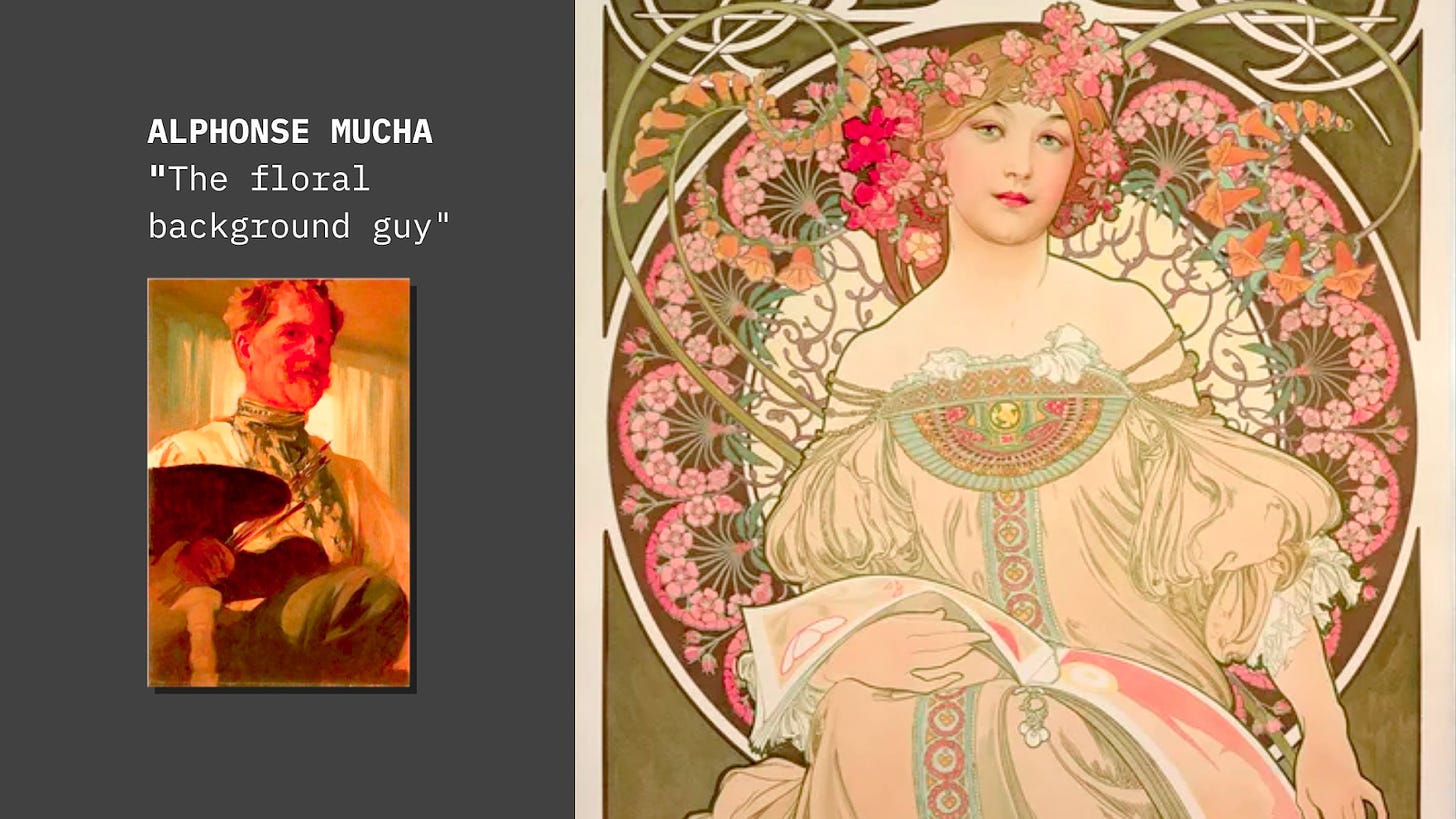

Maybe you recognize the flowery, fluid, feminine style of art above. Mucha was one of the first artists to popularize Art Nouveau in the late 19th century. It was made famous again in the 1960s when everyone started tripping and dressing like the women in Mucha’s paintings.

Mucha was etched into history as “the floral background guy.” This must be his singular passion and dedication, right? Well, no. Quite the opposite. He was more interested in religious iconography and Slavic history, but Art Nouveau paid his bills.

Fame has a tendency to distort the true intentions of an artist. His personal brand as the “whimsical garden painter boy” is simple and catchy, allowing it to spread and spread and spread until he makes it into art-history textbooks, but the “real” Mucha is way more complex.

A false caricature is the price of selling out, but in the end, it proved to be worth it.

The garden style brought Mucha freedom, allowing him to graduate into a new paradigm of art, one that almost nobody knows about, but one that was the fulfillment of his life’s destiny (and his country’s destiny too). There’s a lesson we can all learn from Alphonse…

I knew nothing about this until I went to a Mucha exhibit in North Carolina last year. Not only did it break my model of art history, but it taught me a lesson on the tension between the public’s narrow demands and the artist’s visionary purpose.

At 30 years old, Mucha was a struggling artist. His past was eclectic; he played violin and sang choir at a cathedral, designed posters for Czech rallies, was rejected from art school, and designed both illustrations and tombstone lettering.

Now he was living in an artist’s shelter and paying rent with paintings.

But in 1894, he went viral.

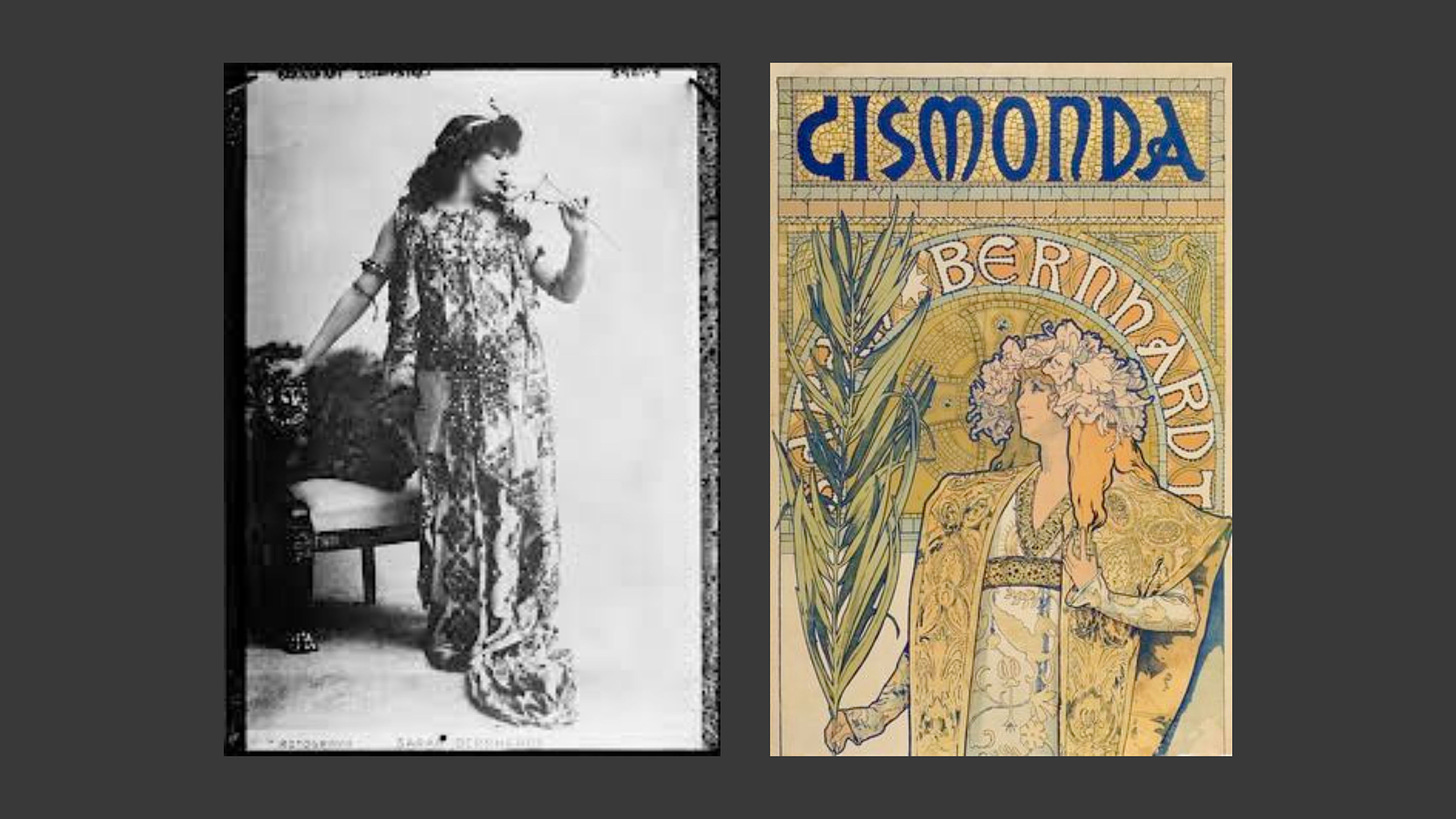

He made a poster for the play Gismonda, featuring the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt (who GPT-4 says is an 1890s cross between Meryl Streep and Angelina Jolie). It was Byzantine in style, and featured an arch that created a halo around her head. She loved it.

Sarah ordered 4,000 copies and plastered them around Paris.

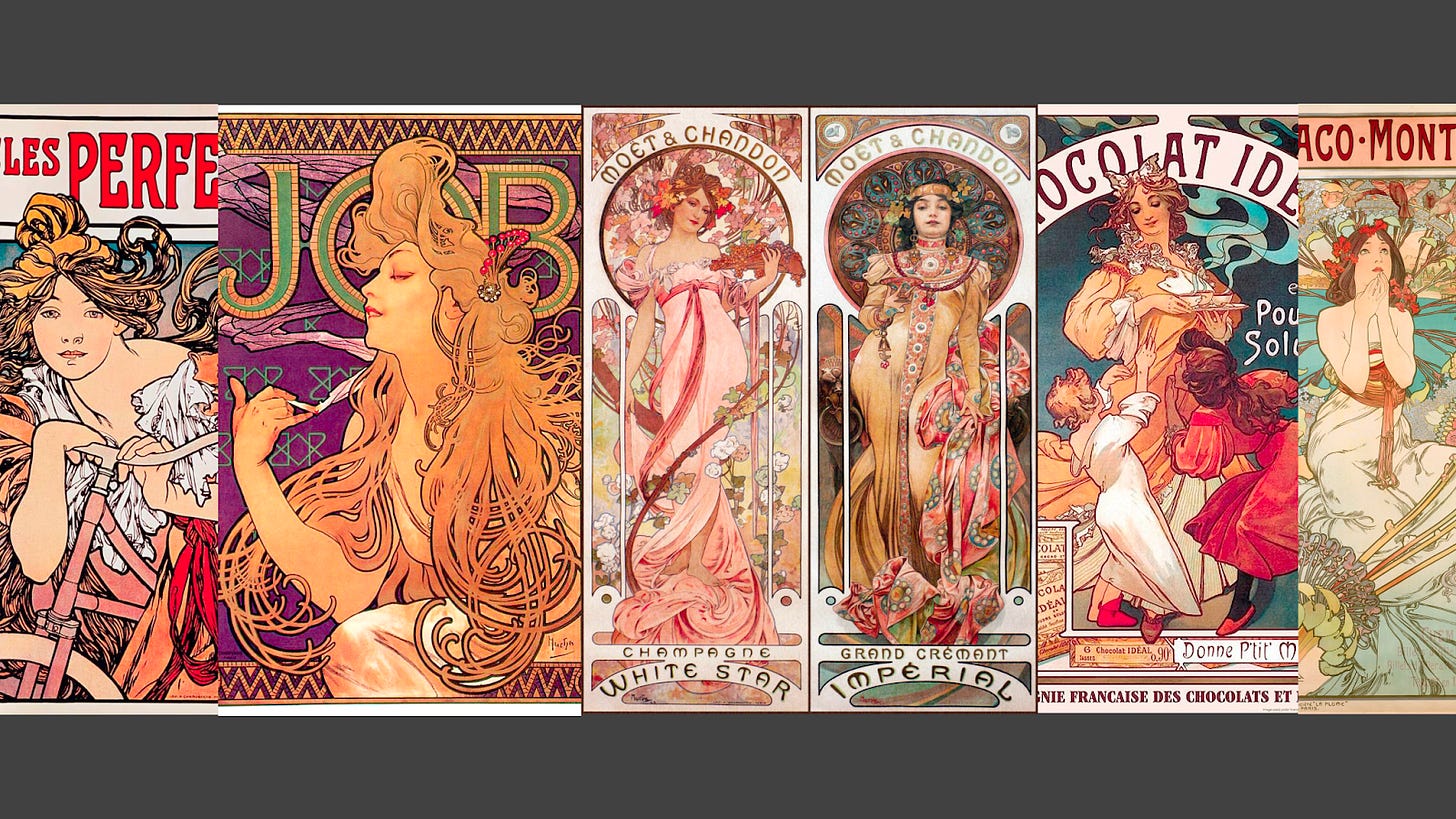

Suddenly Mucha had dozens of companies begging for Angelina Jolie garden drawings with their logo on it. They wanted the “Sarah Bernhardt style” to sell their products. What did he do? He needed the money. He said yes.

Strolling through the museum, I was shocked to learn that Art Nouveau was unleashed to the public through a nefarious purpose: to sell cigarettes, champagne, casinos, Nestle’s chocolate, and bicycles.

What? It’s as if capitalism hijacked nature, held a gun to its head, and forced it to dance for its consumers. Mucha was the struggling artist, and so he was the conduit.

From 1895-1904, Much appeared to be a one-trick pony, rendering hundreds of versions of curly-haired women in serene gardens, over and over.

His commercial work brought him both stability and fame. It enabled him to move into a 3 bedroom apartment in Paris with a dedicated art studio. He was featured in exhibits & magazines, and was known internationally as a pioneer of Art Nouveau (he was so synonymous with the style, that many referred to the whole style as his: “Le Style Mucha.”)

Was Art Nouveau the entirety of his artistic vision? Definitely not. Beneath his public caricature was a complex and multi-faceted person: he was Mucha the mystic, Mucha the Slavic nationalist, Mucha the teacher, the dissector, the experimenter.

He didn’t over-index on what the public wanted from him.

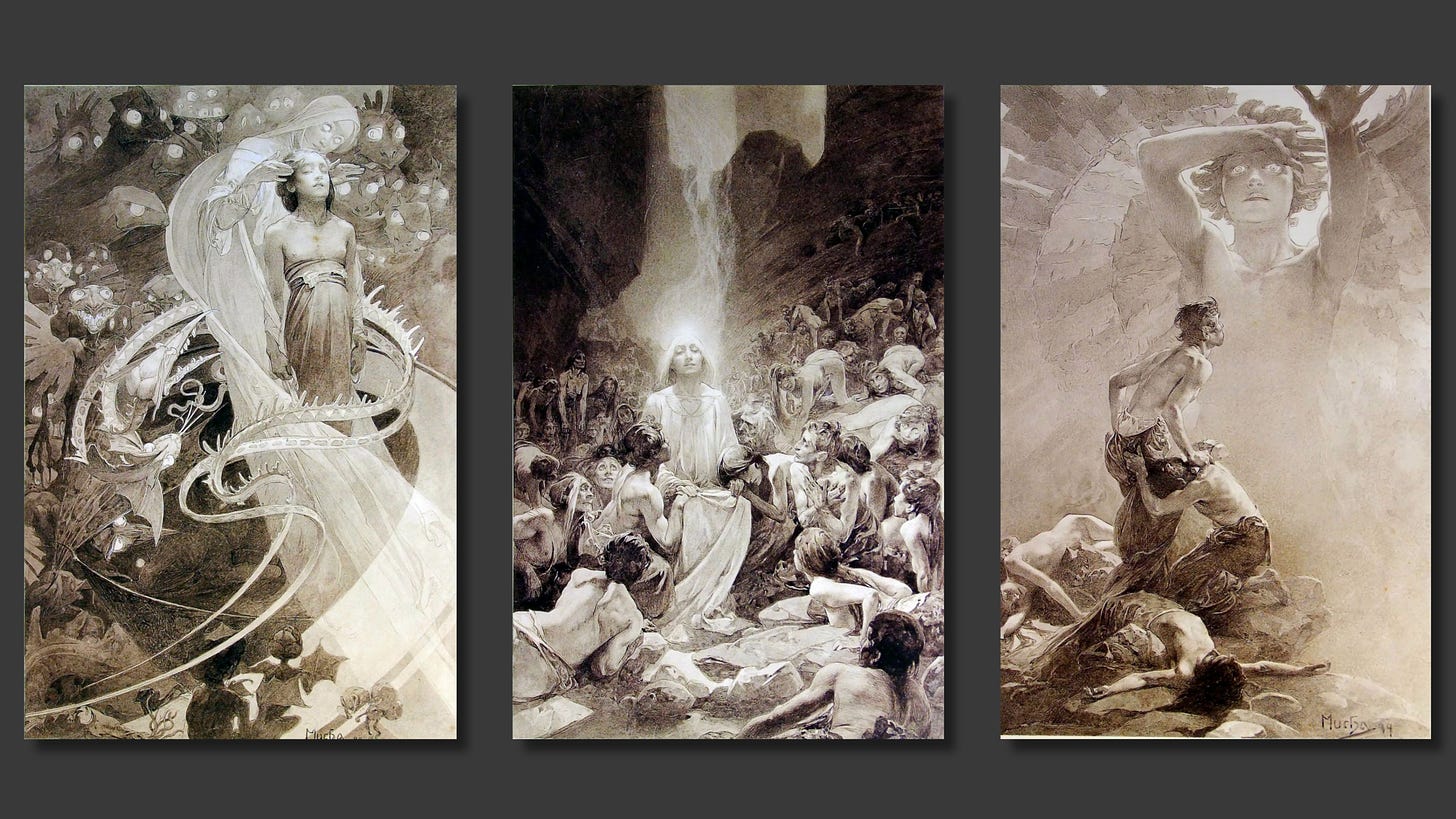

If you look at some of Mucha’s personal art from 1895-1904, it’s shockingly different.

In that North Carolina gallery, I saw a series of paintings called “La Pater,” that sent shivers down my spine. It was the eeriest Christian art I’d ever seen, more transcendental than anything in the Vatican.

There were 7 paintings, each representing one line of the Lord's Prayer. At first I had no idea it was Mucha. It was radically off-brand: no color, and all the pretty gardens were replaced with eerie visions of suffering, transcendence, and glowing-eyed demons. It was a serious work of mysticism, and definitely not a vibe you could use to sell Pepsi Cola.

When did he make La Pater? 1899! At the peak of his popularity for “Le Style Mucha.”

While his “meme-self” was going viral selling cigarettes and biscuits in international magazines, his “real-self” was untethered, moving in the same circles as other rogue artists, mystics, and nationalists.

Mucha's "meme-self" (the floral background guy) enabled his real-self (the Pan-Slavic mystic painter) to come to life. Selling out worked, because he didn’t lose himself to his public image. His commercial work paid well, letting him practice and experiment, and ultimately enabling him to pivot into a new career that was totally on his terms.

In 1904, Mucha stopped taking commissions. Instead of seeking more money and fame, he began an all-consuming passion project that would take him 18 years:

The Slav Epic.

Mucha used the money from his Art Nouveau work to buy 27-foot canvases. His lifelong dream was to render epic scenes of Slavic mythology. In a letter to his wife, he said, finally, he'd be able to make something good, "not for the art critics, but for the Slavic souls."

Mucha personally funded this project for a decade, blowing through his own savings. It was a financial strain. Thanks to his reputation, he was able to find funding from an American industrialist who shared Mucha’s interest in Slavic culture.

Alphonse Mucha created 20 of these masterpieces.

The project came at a time when the Czech Republic was reforming after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire. He became a figure in the Slavic independence movement. They asked him to design the currency of the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

These projects are "off-brand" & unknown to the international public. But to Mucha, it was all that mattered. The commercial work brought Mucha to his destiny. Years before he ever took an Art Nouveau commission, he dreamed of making art to honor his Slavic roots. It happened. And it happened largely because he was willing to play the mini-game of garden advertisements.

The tensions of online creators

Mucha gracefully straddled the line between commerce and visionary art. This story played out over century ago, but the tensions Mucha faced haven’t gone away in our digital age. If anything, they’ve increased. Thanks to our hyper-connected social platforms, the temptation to brand yourself into a commercial vehicle is more accessible and appealing than ever.

So what then? How do we translate Mucha’s story into lessons for today? Do we submit to the algorithm for 10 years and pray that

”one day” we can return to the work that matters?

No. It’s more nuanced than that. Mucha’s pursued his commercial phase in a balanced and tactful way. There are a few points we can extract and codify for our own creative practice:

Double down when you pluck a nerve. A “pure artist” might’ve resisted the endless stream of Art Nouveau commissions. They might’ve resented the “floral background guy” reputation too. Don’t ignore the market’s taste. If you pluck a nerve on the Internet, double-down and ride it out; see it as a fortunate opportunity. It may define you, but it doesn’t have to consume you.

Get paid to practice your craft. Even if your commercial work is off-spirit, it can still elevate your technical craft. Mucha was fortunate to have paid himself through painting, printing, and lithographs. If he spent 9 years distracted with non-artistic odd-jobs, it would’ve been hard to bust out the “Slav Epic” from a cold start. In 1901, Mucha even released “Documents Decoratifs,” a study that broke down the craft of his organic style, but outside the context of advertisements.

Pursue off-brand experiments. Don’t become pigeon-holed by your public brand. Remember Mucha’s “La Pater” Christian experiment? Even if you become a one-trick viral sensation, find and protect another outlet for your weird explorations. Take the stuff that doesn’t get views or money just as seriously as the stuff that does. Don’t over-converge on the expectations of markets, and trust your inner-conviction, even if people don’t get it yet.

Don’t lose sight of your purpose. A commercial boom is a blessing, but be careful. Don’t let success consume you. Know when to close the valve. Don’t chase fame and money for fame and money’s sake. They’re the means to your vision, not the end goal. In Mucha’s case, he stayed level-headed during his 9-year commercial stretch, and it enabled his 18+ years phase of artistic freedom.

If we had to distill this all into one point, what is “The Mucha Method” in today’s Creator Economy?

It’s all about the straddle.

There is a spectrum between [the marketer] and [the artist]. The marketer has a consistent brand identity and pre-designed content strategy, while the artist is a rogue explorer, sniffing ideas and digging to see what emerges. The marketer writes for their audience, the artist writes for themselves.

Some people pick one or the other.

Some people try to balance the two.

Instead, straddle both sides in an extreme way. This is what Mucha did. He took over 100 commissions replicating the same style (the popular style). This is Mucha the Marketer. But he also pursued his own weird off-brand experiments as Mucha the Artist.

My thesis is that being a marketer on social media actually enables your ability to be an artist in your essays.

Check out my latest Twitter threads. They’re all about writers and the craft. Focused. On-brand. Commercially-viable. This is the approach of the marketer. I updated my header and made my bio value-focused: “Using visuals to help you make sense of history's best writers.” This is Michael Dean the Marketer. Through being consistent, I’ll develop my own “Le Style Mucha.”

Vonnegut, Vonnegut! (a visual thread on repetition for writers)

Beyond Architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright (he was a writer)

Hunter S. Thompson’s Epic List Sentence (list sentences)

Untangling the Myth of Jack Kerouac (a writer’s biography)

Check out my latest Substack essays. Random AF. No discernible theme. Confusing for newcomers. No one can define this body of work (including me) and that’s the point. This is the approach of a stubborn artist who relentlessly chases their curiosity, regardless if it’s legible to anyone else. To someone who only knows my craft work on Twitter, they might be shocked to find a “La Pater” on my Substack.

Teleportation, $97/month, coming soon (Apple’s XR headset)

Greenwood Lake (stream of consciousness about upstate New York)

Resurrections on Demand (put LSD back in the communion wine)

The 1,000 Day Molt (how to make decisions like an insect)

There’s a very intentional delineation. On Twitter, the goal is to stay on topic, follow the metrics, and refine my value-proposition. But Substack is my protected place. It’s an oasis. I force myself to pivot topics each week, follow curiosity, log furiously, and write for no one but myself.

Either of these approaches are lacking on their own. A pure artist lacks reach. A pure marketer lacks spirit. But if you can embody both parts, they weirdly orbit around each other, sustain motion, and accelerate in force. Since I know I have an “uncorrupted place of artistic boundlessness,” I feel totally fine, in fact, excited, to become a marketer on Twitter. I used to loathe self-promotion and resist defining myself, but now I see it as this isolated, illusory, temporary mini-game (like Mario Party).

Approaching both is complex. It’s a paradox. Definitely easier said than done. My Substack self publishes and walks away. My Twitter self publishes and nervously checks notifications every 10 minutes. Attention is an alluring, poisonous fruit. Unnatural doses of it can short circuit any psyche. None of us are wired to be celebrities, and if we’re not careful, we’ll get tricked and devoured by our meme-self. I do think balance is possible, but only if the artist has a resilient, self-aware core.

That’s it. Straddle the paradox. Be an uncompromising artist on one platform, and a relentless self-promoter on another. The marketer enables the artist, and the artist grounds the marketer. They require each other to survive.

So don’t pick. Do both (do The Mucha Method).

Let’s riff:

Where do you stand on the artist <> marketer spectrum?

Do you think it’s possible to straddle the two?

Does public image need to match the full self?

I just reposted your last four spectacular paragraphs over to notes. I mean the whole thing is good, but it was like watching a fireworks display the way you light up the sky with multiple beautiful insights at the end. By the way, I agree about Twitter, now seeing the potential there, where there is much more room for the art of writing than I imagined.

I love this, especially the idea that you don't have to sacrifice your artistic integrity to make what matters to you, BUT the art your soul calls you to make and the art that you enjoy making and get paid for do not have to be the same.