Professor Tootzi was a rude and abrasive genius, an architecture professor so dedicated to his craft—hand drafting 3 hours a day for 50 years on imaginary projects—that he evolved into a snarling creature, one who waddled, talked to himself, cursed in Italian, and rubbed his nipples when thinking. It worked.

His own drawings had a mystic quality, so I decided to trust him. He turned me from a near drop-out to one of the top designers in the school. Hands down, the best teacher I ever had. I learned to find his insults endearing too.

“Shut up, already! Are you an architect or a critic at the New York Times?” Tootzi had zero tolerance for process, explanations, poetry, or bullshit. He wanted to see my drawings and models. Great work speaks for itself. Despite his weirdness, Tootzi instilled in me a philosophy of rationalism: that there are objective criteria behind works of art.

The lessons I learned from him in architecture shaped my thinking around writing. Are there invisible patterns that underlie all great essays?

Take the time to learn the hidden language_

In architecture school—twice a week—everyone in Tootzi’s studio brought in their little hand-made paper models of fake buildings (which sounds cute, but people would take amphetamines, stay up for 70 hours straight, and brush their teeth in faculty bathrooms, just to make their fake paper buildings as elegant as possible). The social pressure was unreal: it was Judgment Day twice a week.

At the start of each review, Tootzi—without letting anyone defend themselves— arranged everyone’s paper models in a line from best to worst. He was rarely wrong. He felt you should know exactly where you stand in the pack, earning his studio’s nickname, “The Lion’s Den” (in case you haven’t picked up on the cult-like intensity of architecture school, around 300 people enrolled as freshman and only 40 graduated–an 87% dropout rate.) One-by-one, he’d pick up each model, rotate it, commend it, critique it, and finally, attack it with a knife.

I may have been extremely sleep deprived, but Tootzi pulled off design miracles, over and over. He was a doctor, a shaman of spatial proportions. It seemed like he could instantly understand and unfuck the saddest heap of paper that dreamt of being a building. In hindsight, his suggestions were so obvious, as if we were blind to the potential of our own creations.

Eventually it clicked. Tootzi knew a secret visual language of patterns that his students weren’t yet fluent in, including me. I got a copy of Francis Ching’s Form, Space, and Order, a visual textbook on the fundamentals of spatial design. I kept it in my backpack and read it obsessively.

Regardless of whether a building is classic or modern, secular or religious, a home or a skyscraper, it is governed by the fundamentals of architecture: a proportion of solids and voids, shaped by walls, floors, and columns, organized by function, connected through circulation, symbolically articulated through light, color, rhythm, and texture, anchored in a site and culture, to be occupied by humans, containing psychologies and biologies, both general and specific. These are the rules. You can’t break them, but you can bend them. It’s a big sudoku: an architect has to synthesize a range of overlapping patterns into a single harmonious thing.

Before I knew the fundamentals, architecture school was a struggle. Despite putting in the work and turning nocturnal, I got a C- in my first design fundies class. I was hopeless, ready to drop out and go to a local community college to pursue a career as a jazz drummer. My mother cried. I stuck with it, studied Ching’s book, and was lucky to have a string of world-class professors.

Within a year, I got very good, very fast. Just a year after almost quitting, I won a school-wide design competition as the youngest entrant. I went on to win all 3 competitions during my undergrad years, and also won the thesis award for the 5-year program. But the biggest accomplishment was Tootzi’s reaction at my final review.

Now, my fake building was made out of wood. The master–feared by students, faculty, and even the dean of the program–picked up my model, rotated it around, asked some clarifying questions, put it down, then paused. “I have nothing to add. This project is tectonically perfect.” He spent the next 10 minutes articulating all the patterns at play to the class.

Editing is easier when you know the patterns_

When it comes to essay writing, the idea of “patterns over process,” is just as relevant.

Tootzi instilled a philosophy of “all that exists is the artifact that’s on the table.” It doesn’t matter if your ideas come from your mind, your heart, your soul, your belly button, the tops of mountains, a bottle of red wine, or from managing an in-house spider colony (this was Salvidore Dali’s process). No matter how you arrive, conscious or unconscious, giddy or trampled, a finished work is imbued with legible patterns that determine how it’s experienced by others.

The patterns speak for themselves. Whatever ends up on the page is self-evident, without context. My college roommate once got roasted by Tootzi for handing out pamphlets before his presentation. “Do you think Rem Koolhas stands outside the Seattle Public Library every morning and hands out pamphlets to persuade you of his brilliance?”

David Foster Wallace had a similar piece of advice for writers: “the reader cannot read your mind.” You don’t get to live in the margins and clarify confusion or expand on your implicit intentions.

Process is extremely important, but more so for the writer than the reader. If your rituals, feelings, and psychology are out of sync, you might not show up to make anything in the first place. It has to be fun. But at a certain point, you need to make the flip and take responsibility for being understood. You write the first draft for yourself, but you write the second draft for a stranger.

So maybe essays always start through some idiosyncratic, non-formulaic, mysterious big-bang, but since readers—by nature of being human— have shared features like curiosity, memory, attention, and linearity, there’s a science in how to make your ideas understandable.

What makes an idea memorable? What makes it believable? How come some titles are catchier than others? How do I hook a reader, orient them, and hold their attention? Why should prose be musical and visual? What are the intangible dimensions of voice? … Are these the right questions? Are there singular answers to all of them? And if so, what would happen if you knew them? Mastered them?

There is a secret architecture behind all great essays, a rational, complex, but finite set of patterns that invisibly operate and affect how our ideas are received. There is a hierarchy of rules that exist and are worth learning. They turn the complexity of essay writing into a set of constraints you can obsess over, master, and eventually, forget. Once you put in the work, the rules become automatic, and bendable; you become so fluent in the science of essays that you can live in the realm of art.

A not boring textbook to visualize essay patterns_

I’ve yet to find the equivalent of Form, Space, and Order for essay writing, so maybe I should write it. Of course, there is an abundance of general writing advice, but I have five gripes with existing writing rules.

Limiting rules: The grade-school rules of writing neuter creativity. The five-paragraph essay. Templates. No passive voice, no conjunctions and definitely no Oxford commas. These are rigid constraints that narrow your possibilities. Good rules are bendable and expansive.

Scattered rules: Lots of known writers present great advice as an unstructured list (ie: Umberto Eco’s 36 rules for writing). Each rule might be great, but they’re hard to remember and implement in isolation. I’m inspired by Christopher Alexander’s “A Pattern Language,” where his 253 rules for architecture are broken up into 25 categories. It’s not just one-off tricks. The rules are organized into a comprehensive system for thinking.

Process rules: Lots of advice for new writers is about how to get started and build a habit. Write every day, make a studio, hone your mindset, organize your notes, be social. There is a huge spectrum that covers everything from cheap motivational porn to sophisticated truths on the psychology of craft. While this advice can be helpful, a textbook on essay craft should be mostly focused on the patterns on the page

Technical rules: Have you read Elements of Style? Writing about writing tends to be dry, technical, and obsessed with “usage” (the smallest nuances of grammar and syntax). Imagine a textbook that’s not boring. Instead, it’s written with voice, augmented with visuals, and it covers the building blocks of composition that actually matter to modern online writers. Similar to a textbook, it will be sprawling and comprehensive, but so tightly organized that you can easily navigate and zoom in when you want to.

General rules: Writing advice is often about prose in general, but essays are a specific beast. An essay is different from a diary entry, a newsletter, and a business memo. It is more substantial than a tweet, and less intimidating than a book. Given an essay’s length, you can get feedback, rewrite it, and still publish every week. Done right, an essay is a timeless artifact that uses language to fuse a human with their culture. Out of all the mediums of writing, an essay is perhaps the one most suitable to be a genre-bender. Where is the writing advice that demands the fusion of the soul of a memoirist, the rigor of an academic, and the pen of a poet?

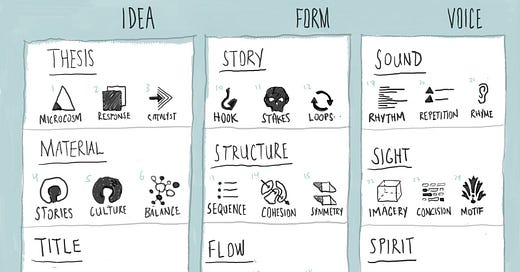

Today I went to the New York Public Library to write out this post and make the sketch below. It’s my attempt to map out what I think are the core patterns behind great essays. It’s structured around 3 core questions (What makes a great idea? How do you give it form? Are you writing with voice?), and then it continuously spirals into deeper sets of triads.

It’s super common for writers to obsess over one part of this map. For example, last summer I spent over 20 hours on a “17 types of repetition Kurt Vonnegut used in Cat’s Cradle,” Twitter thread. Repetition is just one of these 27 patterns, and there are (at least) 17 sub-concepts within it. This map might eventually be a scaffolding that organizes over 500 writing principles, each with multiple examples and rubrics. To start, I want to keep the big picture in mind. I want to make the case that if you’re an essay writer, each of these principles are equally important.

Through 2024, my goal is to write an essay for each of these 27 patterns. I can make the map, but I haven’t internalized every pattern yet. Through writing and talking about these ideas, I imagine it’ll all sync in. It’s not enough to know the secret architecture, it has to be digested, practiced, and etched into your subconscious, until eventually you forget all the rules and devolve back into some refined beast that instantly shapes primal brain putty into its most potent form, making strangers laugh, weep, shiver, make crazy life decisions, and become your friends.

Let’s talk writing_

Whether we’re friends yet or not, I’d love to connect with you and learn about your relationship with writing essays. I’m bursting with ideas on how to structure, present, and build community around these patterns. I want to create the ultimate essay companion for you, but I want you to tell me what would be most useful. Plus, it’s nice to put faces to email addresses. If you have 30 minutes, let’s do it.

Consider this comment a pre-order!

What an intro! I’m so excited for this. And great job telling the story of Professor Tootzi. I could see him at his drafting table and could hear his insults.