It begins. Welcome to the first chapter of Essay Architecture. In The secret architecture of great essays, I announced a 27-part framework (nothing crazy) and this essay on Thesis is an introduction to the first 3 patterns: microcosm, response, and catalyst.

Consider these “element overviews'' to be 200-level theory posts that are free to the public. Following each one will be three 300-level “pattern” posts that dive deep into details, examples, and prompts; these are for paid subscribers ($10/month).

A dirty word_

When you hear the word “thesis,” what possibly comes to mind is a 426-page typewritten dissertation that takes 3 years of library hunkering before it gets ransacked by a committee of heads in suits. The word screams PhD. It sounds like a concept reserved for the academic elite. I’ve been reading the 1977 book How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco, and it’s as old-school as you would expect (much of it describes how to research in the pre-Internet world); it’s also filled with gold.

The essence of a thesis is important to writers of all styles. Even a 500 word single-sitting Substack rant about your love or hate for Superbowl ads will benefit from having a thesis.

A THESIS is a unique perspective, anchored in experience and culture, that organizes supporting material, to change someone’s mind. It is singular: the center of the mandala, from which every sentence dances around.

Since ancient times, it’s been known that effective communication is rooted in a central kernel. In Rhetoric and Poetics, Aristotle wrote about the importance of using a focal point to unite diverse components. This shows up in every discipline under different names: artists have a concept, fiction writers have a theme, lawyers have a central argument, scientists have a hypothesis, poets have a motif, songwriters have a chorus, anthropologists have a theory, designers have a scheme, architects have a parti, etc. In order for a work to be digestible, persuasive, and memorable, the parts have to link into one big idea.

Regardless of the kind of writer you consider yourself, there’s much to learn from academic writing. I believe an essay is the most flexible written medium, and it calls for a fusion of genres: the soul of a memoirist, the pen of a poet, and the rigor of an academic. By learning to shape a thesis, your essays will become more than gripping stories with beautiful sentences, they will help you and your reader make sense of the world.

Don’t be intimidated. A thesis isn’t massive, complex, or tedious… it’s the opposite: an indivisible, tiny–dare I say, atomic–idea. (entering the James Clear distortion field.)

Today, we’ll talk about what a thesis is and how to arrive at a good one, but we’ll start with the confusion that emerges when it’s missing.

The hydra problem_

A thesis prevents the hydra-like expansion of ideas. The hydra is a multi-headed swamp monster from Greek mythology, and if you cut off one of its heads, two grow back in its place. Through effort, you actually worsen the problem. Writers face hydras all the time. Lost in the joy of coming up with and connecting ideas, the undisciplined writer accidentally summons a monster.

Before I published online, every idea I started would spiral out of control. The problem? I didn’t have a clear thesis. I’d begin with a vague intention–“Let me write about the Metaverse today”–and weeks later, I’d have over 10,000 words with no end in sight. The more I wrote, the more the scope grew. Every new paragraph would provoke new explorations I couldn’t resist. Before I knew how to shape a thesis, my drafts would get bloated with tangents, digressions, and backstory. It was an information-rich clusterfuck. Without a central anchor, I’d get devoured by my own hydra, every time.

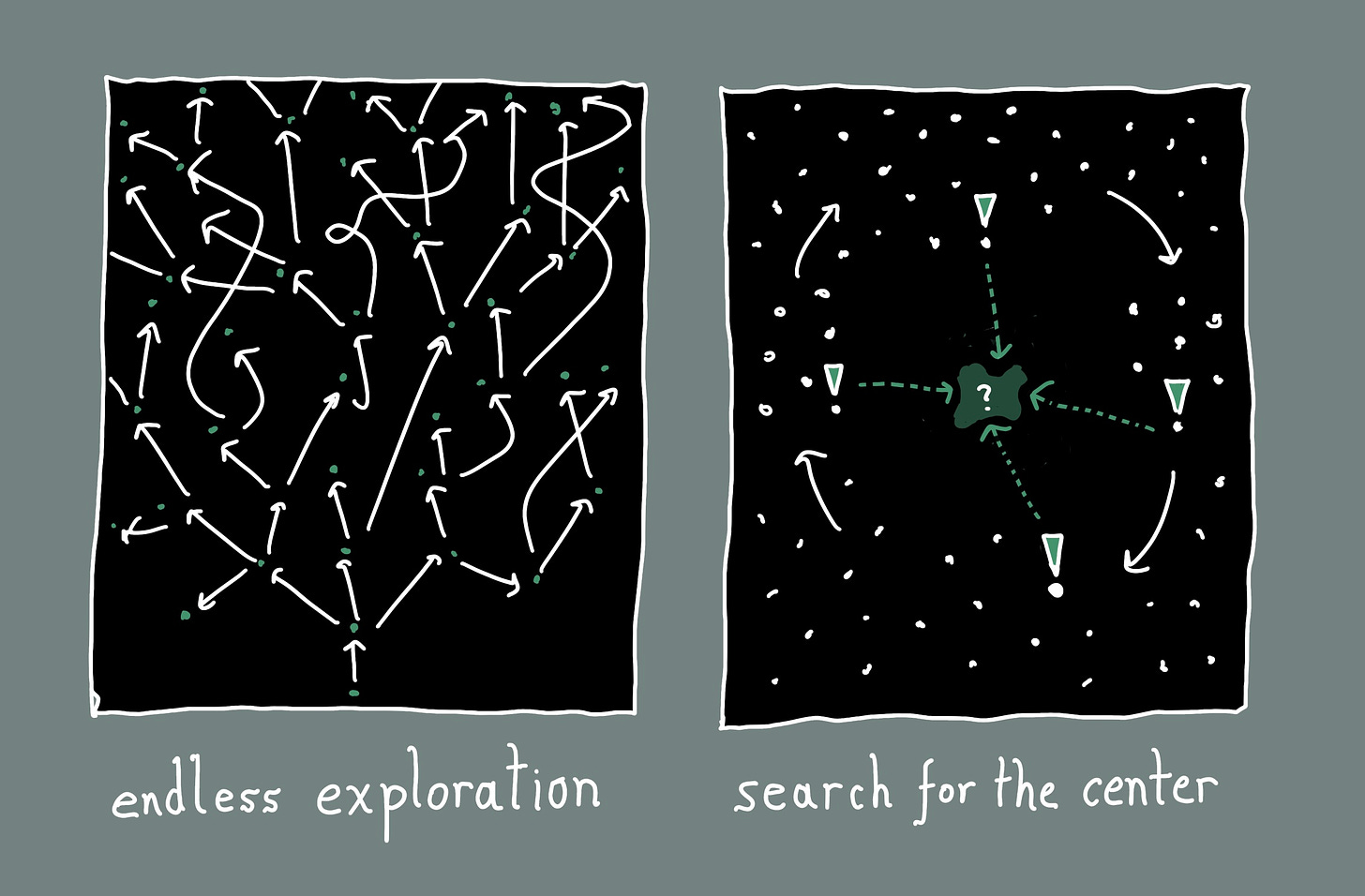

The search for the center_

Of course, as writers we have to explore. Both Paul Graham and Salvador Dali agree–the pragmatist and the surrealist never agree–that you can’t know your thesis before you begin.1 But the manner in which we explore is critical. We don’t want to expand endlessly outwards and keep everything we find. Instead, we want to explore with the goal of discovering the best possible center–our thesis. Once we find it, the trick is to cut everything that doesn’t belong in its orbit, and then re-explore from that new vantage point.

A thesis is a unifying perspective. It lets different ideas coexist by having them all point back to the same central core. An essay should only ever have one thesis; this might seem obvious, but it’s hard in practice. Half-a-dozen competing thesis ideas might slip into a first draft, and in that honeymoon phase, the writer loves them all equally. Without a unifying center, the reader wades through serious friction.

The mind craves unity_

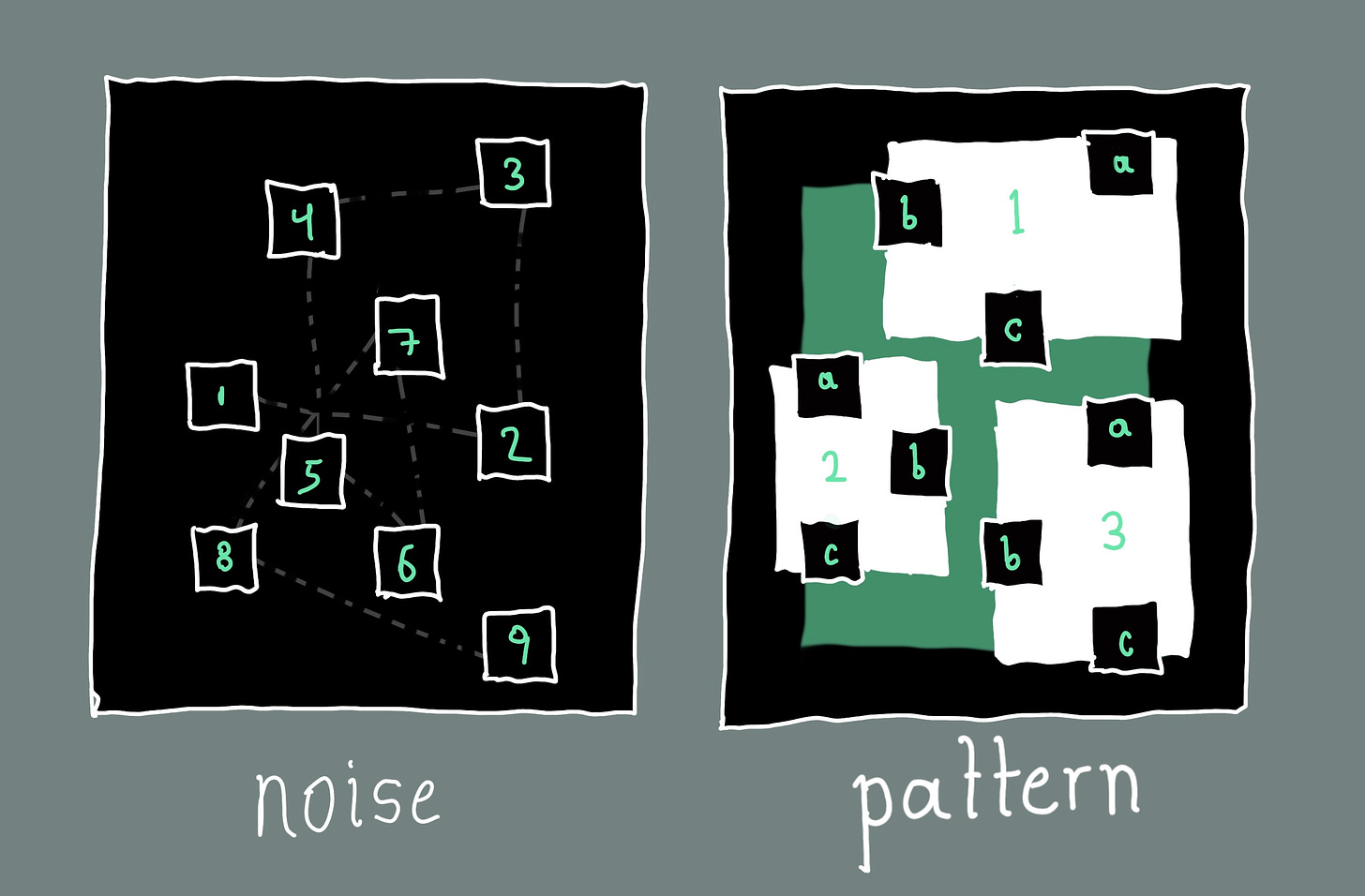

The mind has limited working memory and needs a framework to assimilate new information into. In 1988, John Sweller ran an educational psychology study and coined the phrase, “Cognitive Load Theory.” Two groups were given a ton of information about the Pacific Southwest. The text was identical, but one group had their data augmented with a main idea and headers, while the other group was dropped into a flurry of facts. As you might expect, the first group was able to recall points and have discussions about them; the other group was totally disoriented. An essay is a linear stream of information, and without a thesis to anchor the details, it devolves into noise.

I’m not saying you need to water your idea down to some minimalist caricature. Of course, an essay can and should house multiple things: a range of anecdotes, tasteful digressions (known as “whale facts”2), and odd associations (like fusing Gumby with Sarte’s existentialism3). But for these oddities to gel, they all need to point back to the same place. A thesis helps you organize complexity.

Never have multiple theses; instead, stretch the density of what you can include in a single thesis.

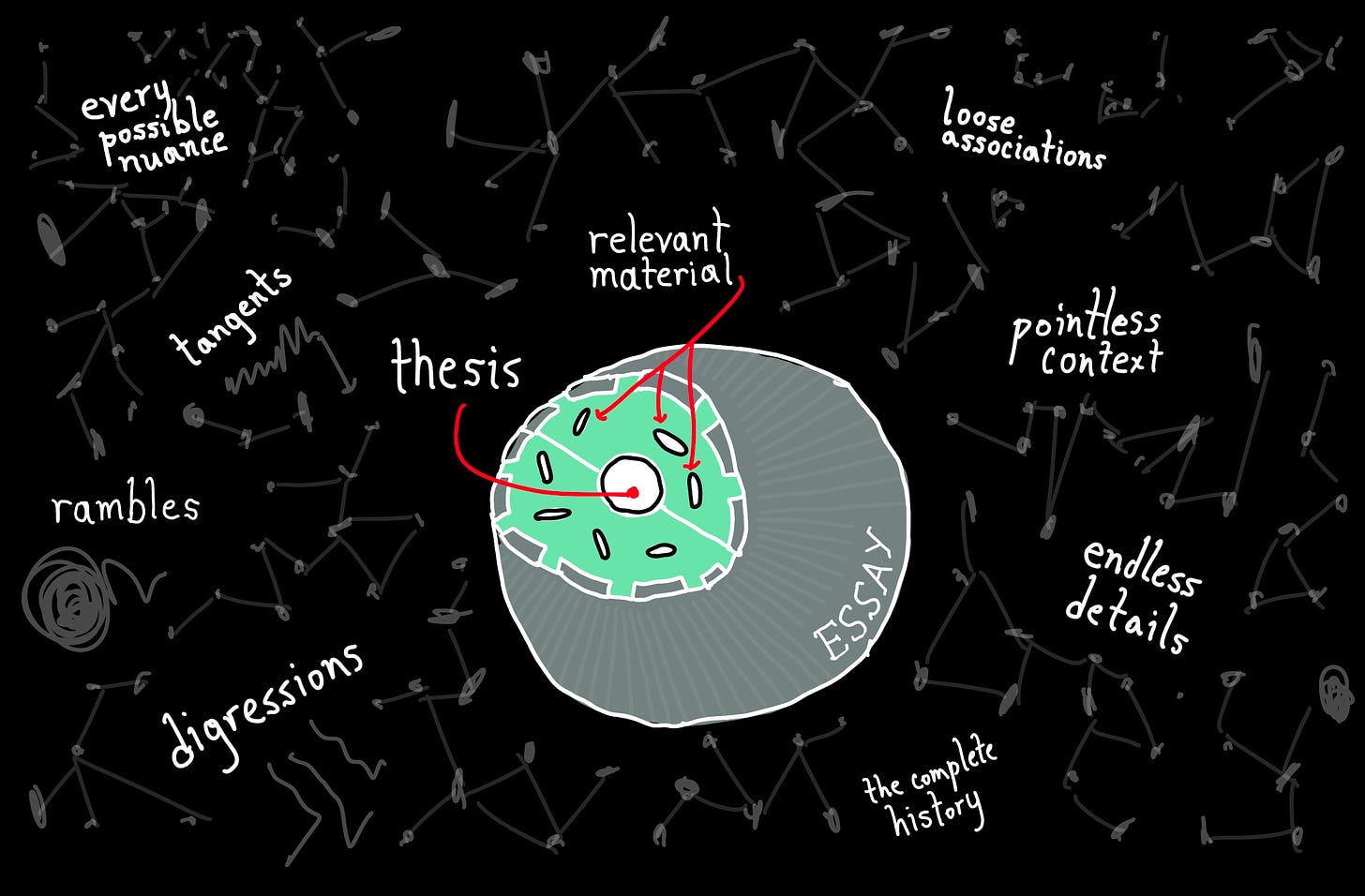

Thesis as nucleus_

To put it practically: a thesis helps you make decisions on what to keep and what to cut. It is a razor, a constraint, a rule, a reducing valve to reality. Out of the vast range of everything that could possibly exist in your essay, your thesis determines what’s allowed to occupy your limited page estate.

You know what else does this? The nucleus of a cell (let’s talk folk science).

Imagine that your essay is a cell and the thesis is its nucleus: the central boss that determines what’s allowed inside. The nucleus sends detailed instructions to the permeable outer membrane. If it lets in everything, the cell will grow uncontrollably and die; if it lets in nothing, it won’t get the proteins it needs (an over-simplification… I am not a molecular biologist).

Before you have clarity on your thesis, it’s hard to set the rules of entry. You might articulate an anecdote in 250 words, when a single sentence will do the trick. When your intellectual security guards don’t have clear instructions, they let everything slide through: the digressions, rambles, tangents, etc. Good ideas never come alone; they always try to smuggle in their friends.

For example, in an essay about “anti-fragility” (when something gets stronger from shock), you can include a wide range of points in your essay, like the resilience of human bones, and how startups learn best from failure. But, if you get into the scientific nuances of calcium derivatives, or the full-history of Y Combinator, you’re adding bloat that does nothing to strengthen your thesis.

Ideas exist in constellations, but if we bring every association onto the page, the essay becomes unbalanced and the thesis is unclear. We need to be discerning, precise, and incisional. Similar to the nucleus, the thesis only lets in the specific sub-points that augment our essay.

The power of purging_

At the top of my draft, I keep a single-sentence thesis statement that I update as I write. It always evolves. As new ideas enter the page, new connections form, and I’ll have a maybe-I’m-actually-writing-about-this! moment. It’s exciting, but slightly terrifying.

By shifting your center, you have to purge material that once seemed great. It’s not fun to kick guests out of the party (but you can invite them to another essay). There is all sorts of psychological resistance to purging: the sunk-cost fallacy, the idea-ego connection, the fear of destruction. Can we pull it off?

Even though it’s tough, purging has serious power. The connection between your revised thesis and the relevant material is only clear once the bloat is carved out. Instead of seeing it as “losing” material, or “wasting” time, see it as a necessary part of discovering your thesis.

Cling to nothing but the quest for a better thesis.

Only through purging can our drafts take evolutionary leaps. A slight pivot in your thesis can result in a totally different essay; a thesis is consequential. Check out these two thesis-statements; one is where I started, the other is where I ended:

Considering they both include AI and the Beatles, they don’t seem that different, but the wording of your thesis really matters. I started out trying to convince my reader that a tsunami of killer Beatles songs was coming, and I quickly learned that people found that terrifying. They were dwelling on the negative effects. It took me 5 drafts to figure out precisely why I was excited about this weird premise: musical abundance and fan participation leads to diehard subcultures, and so AI is about to do to all bands what acid did to the Grateful Dead.

The refined thesis gave me clarity on what to cut and what to add. I removed all of the AI techno-babble and most of the speculations on how people might make music in the future. I re-centered the piece around my experiences and yearnings as a hardcore Beatles fan, and showed how this future of fan fiction will resolve some open-ends from my past. The final essay was completely different, way more personal, and seemed to convince the skeptics. I would’ve never arrived at Lucy in the Sky of Large Language Models, if I didn’t purge most of what was in my first draft.

The 3 patterns of a great thesis_

Writing an essay is something like an alchemical quest: we seek to turn ordinary insights into linguistic gold. The path to do this is to continuously refine our thesis–by melting it and recrystallizing it over and over (or at least once)–until it hits something that feels like max potency.

As I’m drafting, I’ll ask myself these 3 questions to clarify my thesis:

Is there a unique frame that illustrates a larger lesson? (a microcosm)

How does my thesis interact with existing ideas that are similar? (a response)

What is this idea implying the reader should do? (a catalyst)

Through the rest of February, each of these 3 patterns will be explored in an essay of their own. There is a lot of freedom in these constraints, and knowing them well will ensure your work is well-scoped, in touch with the public discourse, and relevant to the reader.

Let’s riff:

+1s: Which points resonated with you and why? Do any examples come to mind that you’d like to share? I see this as an evolving document, and like an architect, I want to incorporate and synthesize examples from different fields.

Challenge: What do you disagree with and why? This is v1, and only through getting into the details can we discover all the nuances.

Share: If you found this essay helpful, I’d appreciate you sharing it so more people can find my project.

Footnotes:

Salvador Dali: "If you understand your painting beforehand, you might as well not paint it." Paul Graham: "Writing doesn't just communicate ideas; it generates them.. Expect 80% of the ideas in an essay to happen after you start writing it." Explore, clarify, re-write.